(The opinions and views expressed in the commentaries and letters to the Editor of The Somerville Times belong solely to the authors and do not reflect the views or opinions of The Somerville Times, its staff or publishers)

By Liam Beretsky-Jewell

Note: This is the first in a series of articles exploring climate change education in Somerville Public Schools

In recent years, several states have adopted standards requiring climate change education to be included in the curricula of K-12 public schools, including New Jersey, Connecticut, and New York. However, Massachusetts has yet to adopt such standards, and the implementation of climate change-related education remains in the hands of local school districts, through the curricula they choose to purchase or design, and the classes they offer or require.

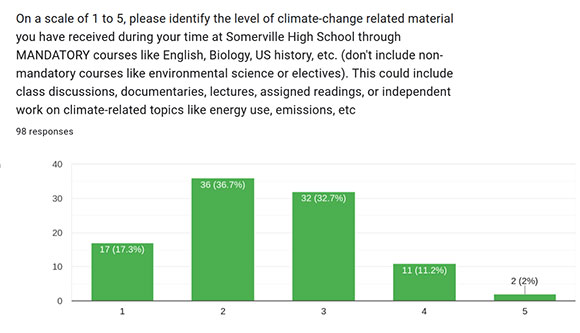

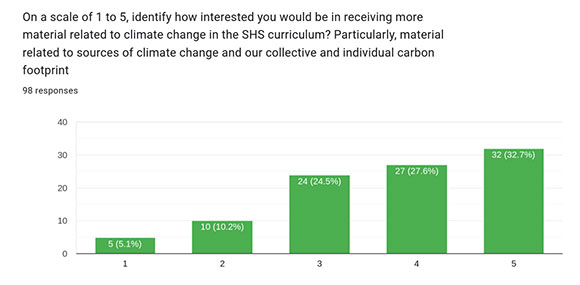

As I approach the end of my 14th and final year attending Somerville Public Schools, I have begun to reflect on my academic experience, particularly as it relates to climate change education. Anecdotally, I feel that I have received a fairly low level of education on the matter through required courses – classes that all students must take to graduate. Beyond my personal experience, I wanted to get a better understanding of other students’ experiences and their interest in weaving more climate change-related material into parts of the curriculum, so I surveyed students attending Somerville High School (SHS). This data was collected from 7 different classes, including 4 humanities and 3 STEM-related classes, in which teachers issued the brief Google Forms survey to their students. A total of 98 students responded to the survey, which included two multiple-choice questions (using a 1-5 scale).

The first of the two multiple-choice questions.

The second of the two multiple-choice questions.

Most students (86.7%) reported receiving a low to moderate level of climate change education in mandatory classes (rated 1–3). Additionally, 84.8% expressed moderate to high interest (rated 3–5) in receiving more such education.

This data aligns with findings from other similar surveys issued to students nationally, such as an October 2022 EdWeek Research Center survey, in which 65% of the 1,055 high schoolers surveyed indicated a desire to learn about how climate change will affect the future.

SHS does currently offer Environmental Science courses at the advanced placement and college preparatory levels, which offer a wealth of climate change-related content. These courses are among the optional elective courses offered by SHS; students can choose to take them to fulfill credit requirements needed to graduate, but the courses are not mandatory. However, in the upcoming 2025-2026 school year, enrollment in [Environmental Science] courses actually decreased compared to this year,” explained Marianna Hosking, the SHS Science Department chair. “I’m curious about why the enrollment in these courses is so low,” she explained, given the demonstrated interest in climate education indicated in the survey.

The survey also included an optional open-response section, where students could share their thoughts on climate education. Nathan Travers, a current freshman, wrote, “I think climate change is a very important issue, as we [continue] down this path of bad decisions.” Nico Brian, a current sophomore, expressed a similar sentiment, stressing that “climate education is necessary if we intend to have a well-informed youth that votes in the best interests of both themselves and the public.” Sihat Mahdiat, a junior, added, “Having a focus on environmental justice in Somerville would be awesome.”

What explains the gap between expressed interest in climate education and actual enrollment in related classes? A significant factor is that environmental science courses only fulfill science credit requirements. Hosking illustrated a typical dilemma that students face: “I’m a student, and I’m interested in the climate course, but I don’t have more science credits I need to take, and I do need history credits.” She further explained, “There isn’t necessarily room for every student who wants to take environmental to fit that in their schedule when they’re taking a variety of other courses, so we can’t really make it mandatory from that standpoint.”

Additionally, most SHS students follow a “default track” in order to fulfill the 15 science credits needed to graduate, explained Maureen Quigley, the SHS environmental science teacher. “[The SHS program of studies] doesn’t say you have to take bio, then chem, then physics.” However, this pathway is reinforced by “the culture at [SHS].” She notes that there are 14 sections of physics at SHS this year, compared to just 3 sections of environmental science, which can be taken as an alternative. Many students may see this path as the most practical, especially with college in mind. Hosking added, “When we’re thinking about what colleges want to see … I think [students] want to make sure that they have bio, chem, and physics on their resume, and that’s really important.”

Given these barriers, the science department has made great efforts to promote environmental science courses, to help provide an outlet for the interest that clearly exists surrounding this topic. “We’ve tried very hard to try to recruit students to those courses,” Hosking stressed. “Current students [have written] letters to their peers. [Ms. Quigley] has done presentations to try to sell the course … We had the elective fair this year and tried to highlight the course that way,” but interest in the course remains low.

As Ms. Quigley and other district faculty have recommended, it may take new interdisciplinary courses, or curriculum and policy changes to help fill this gap. “I don’t think we’re doing enough. I think there’s a desire in Somerville to make things better, to be progressive.” In her experience speaking to students, “there is a strong desire for classes about environmental science, environmental justice, environmental policy … but very few students have access to it.”

The next article in this series will discuss potential solutions, including interdisciplinary environmental science classes or the integration of environmental science into existing curricula, as well as some barriers that may make these solutions challenging.