*

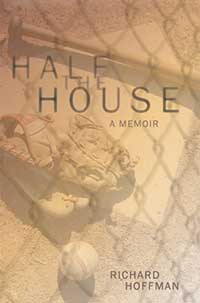

From Richard Hoffman’s website: “Against the back-drop of post-war, blue-collar America, Half the House tells a story both intensely personal and universal. Depicting his family’s struggles to care for two of his brothers who are terminally ill, Hoffman also recounts the horrific abuse he suffered in secret at the age of ten by his baseball coach. In a memoir Time magazine called “spare and poignant,” the author explores the ways in which grief and rage become a tangled silence that estranges those who need each other’s love the most, and demonstrates the healing power of truth-telling in both the personal and public spheres.”

I had the pleasure to talk with Hoffman at the Bloc 11 Cafe in Somerville, MA.

DH: This memoir certainly wouldn’t be considered a journalistic account.

RH: I don’t think there is anything journalistic about it. It is a series of scenes that form make a narrative. I came to this as a poet. I believe the sentences should sing. And if they don’t, the memoir is insufficiently artful.

DH: I see you used a Camus quote in your memoir, “Freedom is not to lie.” Did you achieve this with your story of childhood sexual abuse and its aftermath?

RH: I have a lot of freedom for having written it. You are not free if you have to lie. Silence is a kind of lie. You have to make ethical decisions about what you will write about people. To say you shouldn’t write anything is nonsense. A student reminded me once that I said, “If we are made of memories, then we are made of each other.” That comes with a lot of responsibility to be fair to people.

DH: How would you suggest creative writing students go about starting their memoir?

RH: The key is to write about a place you felt safe and secure in. Everybody had a place to go to feel safe as a kid. Maybe you had a favorite tree to climb, etc. To write about this connects you to your interiority. And from their you can go anywhere. You can go outward from this. You are more in touch with yourself. Where most memoirs fail is with the “I.” The characters are not fleshed out. The character doesn’t have a sense of his or her self. The reader will not have the sense who the character is at that moment in time.

DH: And in your memoir there was an underground crevice that you kids used to go to.

RH: Yeah. We used to go into the sewers. It was like a big concrete room. People are always in a rush to tell people what happened to them. And what happened to them is not as interesting as getting to know who you were then and now.

DH: You organized the memoir by years. Why?

RH: I couldn’t figure out any other way.

DH: Did the memoir go through many drafts?

RH: The memoir took me 15 years to write – so yes, a lot of drafts. You know, I never meant to write a memoir. I was and I am a poet, basically. The book started out as scenes. It bodied forth on its own. When I realized it was to become a memoir I panicked. I thought I am not a prose writer. I don’t know how to make a story. My skill as a poet worked for a memoir – after all it’s all about language, isn’t it?

Reader Comments