*

Review by Kate Hanson Foster

Iron Moon, An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Poetry originates from the documentary of the same name directed by Qin Xiaoyu and Feiyue Wu. This collection gives voice to the voiceless – unknown names penning a “sharp-edged oiled language of cast iron … language of tightened screws.” (Alu, “Language”). To be a migrant worker in the 21st century is a calloused portrayal of rural residents voyaging into the city for the first time, abandoning their autonomy and transforming into human machines:

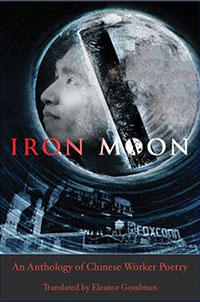

Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Poetry

Edited by Qin Xiaoyu

Translated by Eleanor Goodman

White Pine Press 2016

“The name blank is easy to fill, each time there’s no need to think about it.

I can write in the color

of mud that my parents use for a name.” (Ni Wen, “Filling Out Job Applications”)

This new reality, the shift from self-sustaining individual to a substratal interchangeable number, renders an uncertainty and spiritual yearning that is exhaustive. “How can trash become holy and pure?” writes, Bing Ma in Cleaning a Wedding Gown. Chen Nianxi writes in Demolitions Mark, “I don’t often dare look at my life/ it’s hard and metallic black.”

To shift from thought to action for extensive amounts of time can bring about a grave personal crisis. The anthology does not bridle the dark confessions of self-destruction, and some poems hit with the brute force of a plain spoken secret: “You will never understand what I have suffered,” writes Li Zuofu in Like a Horse at Full Gallop. “After work, the handwriting gets fuzzier/why not just turn to ash?” writes Hubei Quingwa in Moon’s Position in the Factory.

The “iron” in Iron Moon is an image that fuses itself coldly and frequently. It is the ear splitting sounds of cutting gears and kinetic friction. Other times, iron is a metal deeply unheard, “Covered by twilight the huge cooling chunk of iron/gives off a darkening silence.” (Alu, “An Elegy for C”) Iron is an all-consuming crude symbol of broken dreams; the ethos of metal and machinery that is a heavy hit on one’s intelligence and artistry.

The term “Iron Moon” comes from Xu Lizhi, who was born in 1990 and was an assembly line worker making Apple products up until his suicide in 2014. To Lizhi, suicide was the only inevitable exit to what felt like a vagrant life stuck indefinitely in an assembly line. To end one’s life is the ultimate heartsick sacrifice to modern industry. The anguish of “iron” is perhaps best described best Xu Lizhi in I Swallowed an Iron Moon:

I swallowed an iron moon

They called it a screw

I swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died young

I swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out life

I can’t swallow any more

everything I have swallowed roils up in my throat

I spread across my country

a poem of shame

The translations by Eleanor Goodman are an impeccable achievement of negotiating two linguistic landscapes. Multiple layers of artistry are at play here, integrating the raw spirit of the original poems while also strategically fitting language into larger aesthetic dimensions. This collection reminds us of the many human complexities of industrial life, and the exceptional literary value in working class poetry. This book should be a staple in every poet’s respected collection.

Reader Comments