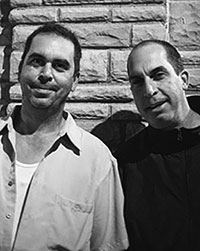

Proprietors of P.A.s Lounge, Tony and Jerry.

By JT Thompson

Tony and Jerry: father and son team at P.A.’s Lounge, an ‘old school’ Somerville bar at the heart of Union Square, which Tony opened 45 years ago, when he was 31. Jerry and his brother Tony Jr. are now the owners; Tony is retired, but still spends many of his days at the bar.

It’s early afternoon when I stop by P.A.’s and find Tony and Jerry there, watching TV and chatting with each other. The otherwise empty bar is dark and cavernous, with a bit of light streaming in from the small front windows. Beyond the main room with the wrap-around bar is another big, open room with a low stage against the wall, tall speakers arranged on either side. Empty stools are scattered beside the wooden counters which stick out from the walls around the two rooms.

Jerry is tall, thin and lanky, with a narrow face and high, balding forehead that make him look even taller; he’s wearing a dark red long sleeved t-shirt and black jeans. While we talk, he folds his long arms across his slender chest and leans back against the gleaming island of liquor bottles at the center of the wrap-around bar. He has a quiet air of amusement when he talks about the bar’s customers. The beginnings of a smile hover in the corner of his mouth as he tells me, “What I like about the job is that you meet different people every day. Over the years you see a lot of Mos Eisley type characters.”

“Mos what?”

“Mos Eisley,” he repeats, a grin spreading across his face. “That crazy Cantina in Star Wars.” He spells it for me.

“During the day,” he goes on, “the ‘old school’ Portuguese guys still come in to see my father. P.A.’s stands for Portuguese American’s Lounge. But at night, these days, it’s the hipsters. I guess they’re calling them millennials now,” he chuckles.

Tony – shorter than his son, with a full head of grey hair, and a little potbelly filling out his blue button-down shirt – is a far more exuberant presence than Jerry. He talks animatedly, using his hands and arms a lot, a big smile flashing across his face. He’s boyish and energetic; you’d never guess he was in his 70s, much less later 70s.

The two seem very comfortable together – Jerry often chimes in to help tell his father’s stories, stories he clearly knows well and still enjoys – and it’s not hard to imagine Jerry’s quieter style developing as a complement to his father’s gregariousness. A painted portrait of Tony hangs on one wall, a gift from a customer.

Tony came to Boston from the Azores in 1958 with his father and sister. While he tells the story, his accent slips in and out of sounding Portuguese and sounding local.

“Everybody talked about the States as a good place to live. I was 17, seeking a better lifestyle. I was planning to make a few dollars, and go back. But things went well.

“My father wasn’t poor back in the Azores. We had a good home, land, he was a farmer. But … the grass is always greener.

“My father was Brazilian, then went to the Azores when he was a little boy. In those days you could come to the States if you were Brazilian.”

Jerry adds, “South America and North – they were considered only one America back then.”

Tony carries on the story. “We needed to have a sponsor, you had to be sure you had a job waiting. My father had an aunt in Fall River, she used to send us money, clothes. She was good to us, did all the paperwork. Your sponsor had to be responsible for you for five years – you couldn’t get state or federal assistance for those five years.

“My first job was in a shoe factory, I put in the eyelets. I did that for three years. Then, in 1963,” he says, beaming, “I became a citizen. And I sponsored my brother to come over.

“After the shoe factory, I went to school to be a machinist. I did that till 1970. Then I went into business for myself. Bought this place in 1972.

“And I’m still here,” he says with solid pride.

“My wife,” Tony goes on, “she’s from Ireland. She became a citizen in 1962. We went out on a blind date, and have been together ever since. Three kids. Grandchildren. Now one great grandchild on the way!”

Jerry, the father of two of those grandkids, tells me that he was born in Somerville, “Just opposite the Prospect Hill monument.

“Not on the sidewalk!” he laughs.

The monument is the two story stone tower that looks down over Union Square. On top of its flagpole is the copy of the flag General Washington flew there on January 1, 1776.

Tony disappears into the back, and I continue the interview with Jerry, who tells me he had a classic, ‘old school’ Somerville childhood. “I grew up playing street hockey, street football, that kind of stuff. We used to just stay out and play on the streets.

“In the summers, we would go with my mother to Dublin, we did that seven or eight times.

“Didn’t travel around the States at all growing up. Dad was always working.”

I ask him what he loves about America.

“Well, obviously some of the freedom you don’t get in other countries.”

“What does freedom mean for you?”

“Not being dictated to, like North Korea or China. Being told what you can and can’t do.

“Here, you can protest, maybe it’ll work. Other countries won’t let you do it.

“Of course, we’ll see what happens now.” He gestures at the TV, where a story about Trump is playing.

“Hope he doesn’t turn into a dictator. He wants to be king. Not in this country! But that’s politics.” He shrugs. “It was the uneducated who elected him.”

I ask him if there are things about America that he thinks are great.

Jerry chuckles.

“There’s a lot of great things I haven’t gotten to see yet.

“I’ve been to the West Coast once. Haven’t had the chance to experience the national parks out there. I’ve been to the Grand Canyon. There’s lots of national parks in California, the Northwest, or down South, that I haven’t been to. The East Coast I’ve seen, from Acadia all the way down to Key West.”

He nods. All natural wonders.

Probably a nice break from dealing with people every day. I imagine Jerry standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon, looking out into all that wide open, empty space, not a customer in sight.

I ask him what changes he’s seen in Union Square.

“It’s changed in many ways. Crime is going down. Lots of newer businesses. Less banks, more cafes.

“Just the demographics in general. It’s very diverse, lots of different cultures. Not so much the ‘old school’ Somerville people around. Like I said, the Portuguese guys still come in during the day to see my father. The younger, hipster crowd comes in at night for the music. We’ve been booking a lot of indie bands.

“It can’t stay the same. I feel it’s gonna change. The established businesses, like us, own their properties, but if rent goes up, everything else goes up. The landlord has to pay taxes, the water bill, whatever else comes along. Plumbers, electricians, aren’t getting any cheaper. If the Green Line gets extended into Union Square, we’re going to have to start charging a lot more for beer!”

An older guy in a grey cap and black leather jacket comes in, sits down, and greets Tony in Portuguese. Tony gets him a beer, which the guy in the cap pours into a glass and slugs down, emptying it only halfway, and then, leaving the half full glass behind on the bar, says, Ciao! and heads back out the door.

I ask Jerry for a shot of Jim Beam, which he pours all the way to the top. I sip it down a bit, then take a stroll around the bar. The older decorations are all sports themed. All the wooden counters, around the bar and against the walls, have colorful player cards from old Boston teams shellacked into their surfaces, football, hockey, basketball. Up on the walls facing the stage are big, new-looking black and white portraits of Johnny Cash and Dylan, in their young and badass days, which I imagine are there for the hipsters, in their beards and skinny jeans.

I am sitting against the wall beneath the posters, sipping my bourbon and writing in my notebook, thinking about the waves of immigrants that have come through this bar, when the smell of espresso fills the air.

Tony comes out from the back with a tiny white cup and saucer in his hand, leans against the bar, and looks up at the TV, where Paul Ryan is talking about a “patient-centric” health care plan.

Tony throws his hands up in the air and exclaims, “How’s the little guy gonna pay for it?” He turns his back to the TV, walks away from it, and throws his hands up again. “How’s the poor guy gonna pay for it? I don’t understand.” He shakes his head. “I don’t understand.”

He sounds exasperated, baffled and disgusted all at once.

I go up to Jerry to pay for the shot, and Tony waves me away.

“Bring us a signed copy!” he says with a big smile.

I make my goodbyes and walk out into the sunshine, wondering if Jerry will run the bar as long as his father has, wondering what changes will come through his birthplace, Union Square, the home of America’s first flag, in the next thirty or forty years.

Reader Comments