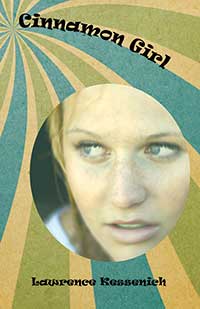

State Rep. Denise Provost reviews Lawrence Kessenich’s new novel Cinnamon Girl. Kessenich is a managing editor for Somerville’s literary magazine Ibbetson Street.

Cinnamon Girl

By Lawrence Kessenich

North Star press of St. Cloud, Inc.,

St. Cloud, MN

The often-repeated cliché about the 1960s is that, if you can remember them, you weren’t there. In his debut novel, Lawrence Kessenich shows us that he clearly remembers those times, and was possibly taking notes. Otherwise, how could he spin out a novel recounting the kinds of events described, in such detail?

Cinnamon Girl is a quasi-picaresque coming-of-age novel (and possibly roman a clef.) Its first person narrator, John Meyer, begins his story in the midst of a political demonstration, as armed police are charging unarmed protestors. It’s the summer of 1969, and John is a youth of his time: self-righteously angry at the conservatism of his parents, earnestly indignant about the war in Vietnam, and furious about the military draft that feeds young men like himself into its maw. Besides having a keen sense of life’s injustice, John is also a sensualist, drinking and smoking reefer while enjoying food, cigarettes, and rock music in the company of friends.

John and his friends are mostly students at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, preoccupied with maintaining their draft deferments while educating themselves out of the boring jobs they work at. There’s a touchy class consciousness about where families live, and fathers’ job descriptions. Yet there’s also the sense that even without these hovering social divides, John and his male friends would still stay at arm’s length, getting stoned together being the peak of their illusory intimacy.

It’s a strong illusion, though, and John becomes close buddies with affable dock hand and student Tony Russo. Or, possibly, John is drawn to Tony’s wife Claire, an enticing green-eyed blonde, with “freckles sprinkled like cinnamon across her nose.” There’s also the attraction of Tony and Claire’s infant son, Jonah; a lure for John, as conflict with his parents makes him want to break away from home, even as his strong love for his big pack of siblings anchors him there.

News of the far-off Woodstock Festival inspires Tony’s friend Tim Kolvacik to supply mescaline to a party at the Russo’s, enhancing the sense of closeness and trust growing between them, Meyer, and Kolvacik’s girlfriend, Mina. Soon after, as Myer recounts, “[w]e became a family almost instantaneously, incestuous longings and all.” A few “inseparable” months later, the Russos, Meyer, and the intense young radical Jonathan Bradford move into a big Victorian house together, setting the stage for “the party months.”

What these young people do thereafter takes place in the shattering news of the Kent State killings and their aftermath; the local playing out of the national student strike; the shaky political alliance among the organizations on the Strike Committee, and the teach-ins, disruptions, and ideological hostilities of the day. Besides its psychological exploration of its characters, Cinnamon Girl is a collection of love stories, and a social history. It will have certain nostalgic appeal for those who came of age in the same era, and may well be a revelation to those whose experience of protest began with the Occupy movement, or Black Lives Matter.

John Meyer is an engaging central character. While he can be petulant and defensive, he simultaneously disarms the reader with his unfiltered candor, his lack of cynicism, and his willingness to behave in ways that are uncool. Kessenich shows Meyer goofing with his much younger sisters and brother, taking them out to a movie (and ice cream before dinner), volunteering to change Jonah’s diapers – a sort of anti-Holden Caulfield; not at all the typical male protagonist of that era.

Although he is an accomplished poet, Kessenich’s prose here is spare and straightforward, moving his story right along. The dialogue has a natural flow, although some of Meyer’s internal monologues about love, concerning cupid’s arrows, and a woman as an “open vessel,” while not unexpected from a besotted 19-year old, are a bit cringe-worthy. The use of cliché, even occasionally, is not what one expects from a writer of Kessenich’s talents.

That said, Cinnamon Girl’s flaws are as scattered as the faint freckles across Claire’s nose. It’s a good read, and a fine first novel. I’m already looking forward to the next.

Reader Comments