*

A new poetry collection is out by Somerville’s Gloria Mindock. It is reviewed here by the noted critic Dennis Daly:

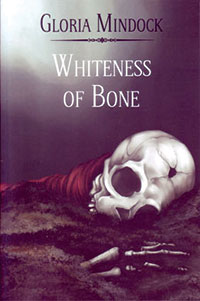

Whiteness of Bone

By Gloria Mindock

Glass Lyre Press

Glenview, Illinois

www.GlassLyrePress.com

ISBN: 978-1-941783-19-1

81 Pages

Review by Dennis Daly

Certain extraordinary people absorb the world’s suffering and cruelty; they identify with the victims of inhumanity so closely that at times they seem to transfigure themselves into exemplars of those unfortunates. Faith healers, saints, mystics all possess a measure of this quality. In hagiography think of Francis of Assisi, Theresa of Avila, and stigmatics like Padre Pio. On the secular side, singular artists also manifest this imaginative and creative trait in different, but no less extreme, forms—including and especially poets.

Gloria Mindock, one of these versifiers of villainy, pens her narrated atrocities with a radiating light of white hot indignation. She aims to shame us all for not listening to the piercing screams of child-sufferers and the horrified protestations of adult innocents against imminent barbarity. Like Cassandra, the poet predicts future savagery and devastation, and, like that prophetess, she feels ignored. From Mindock’s opening poem, In a Dark World, her obsessive need to voice the world’s Manichean reality and her sense of crushing injustice drives each poetic commentary. The poet questions her own worthiness in the heart of this piece,

Day after day, death happens…

despite the sun coming out to

show the blue of the sky.

Beauty and ugliness in battle—

Light and dark in battle—

Each day, a tug of war and each day,

each side wins somewhere in the world.

You told me I was light in a dark world.

Why did you do this?

Do you know something I don’t?

Railing against bestiality is, in a sense, railing against human nature, since humans are, at least in part, beasts too. Altruists, such as Mindock, want to invent a civilization of angels, who answer to the golden rule rather than base instinct. It’s unattainable, of course, but quite necessary in the long evolution of mankind’s soul. The poet in her opening stanza of Call describes our present state,

Pounding, beating…

Possessing the prey, like an

animal with no cares but survival.

This is what we do to each other.

Some defeat is on purpose and the power,

spills out of the soul.

Blood tries to swallow the world.

Mindock intimates that the end is near in her apocalyptic poem entitled End. Her persona plays hide and seek in little-girl fashion, waiting for the missiles to strike. Personal death powers these words, but total annihilation also seems expected. For the dead, these conclusions are, indeed, synonymous. Mindock’s persona channels a fiery fate,

My hands are together as I wait, but first

I must put on a pretty dress.

People are weeping, not me.

I welcome the heat disintegrating my body.

It is time to slide down to the floor,

feel the rush around me.

Nothing remains…

State terrorism casts its shadow within Mindock’s poems. In her poem Missing she effectively calls criminal governments to task by conjuring up apparitions of the villagers who “died with grace” to bear witness to the horrors. The Disappeared understand that the poet’s words embody their existence once more in mnemonic sympathy,

They can hear me speak. Their hearts beat

faster and they understand.

They feel my breath—

This is not un-human.

Overhead birds sing about what they saw.

It is not joyful chirping.

This evening, there is a big light shining

from the countryside.

It is my fault, I lit the match so

the world could see, remember.

The military killed them.

Whiteness of Bone, the title poem, fluctuates between objective reflection and emotional response. Mindock rationalizes that war and genocide are always with mankind. Cruelty grows out of nature. Slaughter seems almost ritual. The poet repeats in this poem and others the image of blood flowing into the ground as if the earth demands this as a sacramental sacrifice. She also channels the dead, her heart bursting with a pointed compassion. Mindock’s dual identity forges a poignant conversation of conscience. The piece concludes with her conversation culling a new identity from moldering bodies,

All the bones saturate the ground.

One can learn about the life and death of the

dead by holding them.

I hear you, know you, there is no vacancy

in my heart as your life closes in.

the whiteness of bone, I caress, kiss and

retrieve your memories for a better life.

Brutalized countries often cannot escape the cycles of revenge and murder. Common people pay a terrible price from both contending sides and many seek refuge. El Salvador emerged from a 12 year war into a hair-trigger existence, the martyrdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero still shining brightly in that country’s collective consciousness. Mindock uses this background in her piece entitled Escape to chronicle the flight of many Salvadorian people to the United States. The poet describes her role,

… hidden in trucks.

Travelling falls into place with rosary beads

in their hands, each bead a prayer to Romero.

Living is a taste I really want for them.

Escaping, a betrayal to El Salvador but

the pavement to a new life is calling.

In America, they have a dialogue

with themselves.

Crying and mourning, loss, a way of life

until the joy of a new oxygen takes over.

Meanwhile, I speak for them. Putting my hand

again on their soil… taking the role of angel, anointing their

foreheads with the soul of a dead one…

Mindock’s poems give witness to an earthly hell. Her collection cries to heaven. Readers of good will, take notice.

The Somerville Arts Council now accepting applications for LCC Grants. The Council awards money once a year to support artists, schools, and organizations in Somerville. The 2017 grant guidelines are now available. Go to http://somartscouncil.org for details.

Reader Comments