*

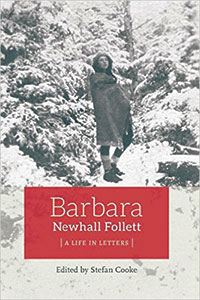

Part of life is losing touch. People disappear from our lives, sometimes never to appear again. Somerville writer Stefan Cooke author of Barbara Newhall Follett: A Life in Letters is not satisfied to let the disappearance of his half aunt Barbara disappear into the ether. With his new book he traces Follet’s life through her letters. Follett was gifted child prodigy writer, who vanished in 1939 from her home in Brookline, Mass. at age 25. She was never to be heard of again.

Cooke has long been fascinated by Follet’s story and writing. He told me over coffee at the Bloc 11 Cafe in Union Square that, “I love her work, her skill with words, language, vocabulary and imagery.” For the book he researched Follett’s papers at the Columbia University’s rare book collection in New York City. Cooke said, “The book is basically a collection of letters to various correspondents.” Cooke told me that Follet did not have a formal education (she was home-schooled), and never went to college except for a few dance classes at Mills College. In spite of this, Follett had the talents and skills of a master wordsmith.

Cooke has long been fascinated by Follet’s story and writing. He told me over coffee at the Bloc 11 Cafe in Union Square that, “I love her work, her skill with words, language, vocabulary and imagery.” For the book he researched Follett’s papers at the Columbia University’s rare book collection in New York City. Cooke said, “The book is basically a collection of letters to various correspondents.” Cooke told me that Follet did not have a formal education (she was home-schooled), and never went to college except for a few dance classes at Mills College. In spite of this, Follett had the talents and skills of a master wordsmith.

At he age of eight Follett wrote her first novel, The House Without Windows. Follett explained that it was about, “…a child who ran away from loneliness, to find companions in the woods – animal friends.” Her father, Wilson Follett (the noted critic), sent it to the prestigious New York City publisher Knopf, and in 1927, when Follett was 12 years old, it was published. The New York Times lauded the book, calling it, “…truly remarkable.” The Saturday Review of Literature opined that the book was, “Almost unbearably beautiful.” Later, when Follett was at the advanced age of 13 (with her parent’s consent) she took to sea as a crewman on a lumber schooner. And, of course, a book ensued: The Voyage of the Norman D. The Times Literary Supplement raved about the book saying it was, “… embellished by a literary craftsmanship which would do credit to an experienced writer.”

But as fate would have it, Wilson Follett left her mother for a younger woman. The father did not provide much money or support. Eventually Barbara Follet’s life unraveled. She got married as a teenager, but the marriage eventually soured. She left her marital home in Brookline, Mass. in December of 1939, never to be heard of again.

Cooke told me he has lived in Somerville for years with his wife, artist Resa Blatman. Blatman designed the cover of his book. Cooke works as a web designer as his day job. One of his projects is the Afghan Women’s Writing Project that publishes the work of Afghan women, hosts an online workshop, and occasionally publishes books by these women, sometimes in their native language of Dari.

Cooke tells me there is an opera planned about Follet’s life, and in 2017 Penguin Books plans to release a critical study of her work and life. Cooke is quite glad to be part of this conversation about this lost genius.

Cooke shared this with The Times:

Here’s an excerpt from a letter Barbara wrote in 1930, when she was 16 and living in New York City. It’s what I picked for the back of my book. The book she was going to write was called Lost Island, which I transcribed and posted on Farksolia a few years ago: http://www.farksolia.org/lost-island-part-1/

“Do you realize that a year ago yesterday I set sail from Honolulu harbor in my beloved Vigilant? I was rather glum all yesterday thinking of it. It hurt. I suppose it will be years before I go to sea again, and I may never even see that schooner. I suppose that I spent about the happiest month of my life during that sea-trip in her. And it lasted even during that week in port, when I took over the cabin-boy’s job, and when Helen, Anderson, and I had cherry- and ice-cream-parties in the cabin after everyone had gone ashore, and when we used to walk up into that virgin forest two miles up the road, and eat salmon-berries. Life was beautiful then. This doesn’t seem like the same era. Here the beauty consists of great stone towers against the sunset—sublime, symbolic, but away above the plane of us poor ants that hustle along the swarming streets at their feet, so engrossed in ourselves that we never even see a fellow-mortal, but bump into him with a bang, and then hurray and hurry on.

Oh, my God, my God!

It makes one’s heart and soul suffer—it stabs them to the quick. Oh, for wings, for wings!

Wings!”

That is, in general, the theme not only of my own heart, but of the book I’m going to write. I ought to be able to write it – I live it constantly. My heart is the field of a thousand battles every day.

Reader Comments