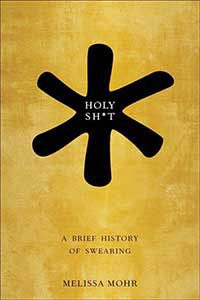

“Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing” is a serious study of the history and meaning of the use of obscenity since ancient times.

By Blake Maddux

Melissa Mohr is a Wisconsin native who has a Ph.D. in Medieval and Renaissance Literature from Stanford University. She is now a Somerville resident by virtue of being married to an MIT philosophy professor.

In 2013, Oxford University Press published her book Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing, which – in its concise 260 pages of text – covers the use of obscenities from ancient Rome right up through the present day. Mohr succeeds masterfully in entertaining and educating her readers with lessons in etymology, religion, history, sociology, and human nature.

However frowned upon, the use of profanity is now and always has been. Mohr concludes that “Swearing is an important safety valve, allowing people to express negative emotions without resorting to physical violence … they are cathartic, relieving pent-up emotion in ways that other words cannot. Take away swearwords, and we are left with fists and guns.”

Mohr spoke to The Somerville Times by phone shortly after the May 1 publication of the paperback edition of Holy Sh*t.

Somerville Times: How is the subject of Holy Sh*t related to the work that you did in graduate school?

Melissa Mohr: When I was a grad student, I ended up writing my thesis about swearing in Renaissance literature, although the book is very different from that, which was an interesting transition, trying to take a kernel of academic work and turn it into something that people might actually be interested in reading. The dissertation kind of looks at what it means to swear in terms of literary theory and performative language. And it only does Renaissance literature – there’s a chapter on [Christopher] Marlowe, there’s a chapter on satire – and looks at it from a more literary angle.

ST: Were you specifically interested in the concept of swearing or did you just need a topic on which others had not done extensive academic work?

MM: I was more interested in swearing. I was originally interested in the literary theory aspect, the idea that certain language can do something very directly, like when you marry somebody, the language is not communicating something, it’s actually doing something. So I was interested in looking at different examples of language that makes people do things directly. So originally the project was going to be this gigantic thing where I was going to look at swearing and humor and pornography. But then I figured out that I had better not do all that and just ended up with the swearing, which is probably the most interesting anyway.

ST: Given humanity’s use of profanity throughout history, should it really still surprise or shock anyone when people use it now?

MM: In a sense, it shouldn’t be surprising, because it has been around forever in different forms. But the thing is, we kind of need it, and so we kind of have to make it shocking. It really performs a variety of important functions in language, and so we kind of need a word that really expresses emotion. When you hurt yourself, it actually is really helpful to be able to – first of all, it relieves pain – be able to communicate to people how this hurts so much that I’m actually violating this social taboo by swearing, depending on the context.

We need these words, and if we didn’t have them we’d have to invent them. In fact, we keep inventing them. When the religious words started to lose their power, then we went to the sexual and the excremental ones, and those are getting less powerful and we’re moving to racial terms as the most obscene terms. So I think there’s always a turn, although it happens very, very slowly.

ST: How is it that the expression “by God’s bones,” which probably no one alive today has ever heard, was once the most profane thing that a person could say?

MM: So the religious words were at the height of their power in the Middle Ages – 1100 to 1400, let’s say, the kind of high point of the power – and society was just suffused with religion and a lot of people’s lives were directed toward God, heaven, hell, sin, punishment. And words, especially like “by God’s bones” for Catholics, were thought to be a kind of perverse version of the Eucharist. In the Eucharist, the priest says, “This is my body” and creates the body of God in the wafer and then eats the body of God. Christ in the Catholic tradition also has a body up in heaven, a physical body. When you swear, you can actually rip that body apart in heaven, which causes Jesus pain and his body is literally bleeding up there in heaven. We don’t think in those terms anymore, but for medieval Catholic people, that really was horrifying. “How could you do that to Jesus?!” So those were kind of the worst, most powerful things you could say.

ST: Were you prepared to have to swear in front of audiences after Holy Sh*t was first published in 2013?

MM: I was prepared. Given that I’m of a generation where the really obscene things to me are the racial slurs, and I won’t say those and I don’t think anyone wants to hear me say those. You have to sort of see who’s in your audience. I once gave a talk at a Brandeis lunchtime seminar for retired people, and I was much more nervous about that because tolerance of swearing goes down as your age goes up. So I was a little more wary.

But I think it is something of a myth that swearing is a sign of ill-education or poverty of vocabulary. A well placed swear word, as Donald Trump knows – although who knows what he’s doing intentionally – can really win over an audience and can make you appear more credible. It really communicates emotion in a way that people can relate to.

ST: Do you have an idea for the next book that you plan to write or are you working on anything now?

MM: Eventually, I’d like to do something on swearing in other languages, which would be a fun thing. But right now I’m doing a kind of history of male and female relationships after marriage. How marriage became the way it is today and how it was different in the past. Looking at friendship, adultery, cross-sex friendships, and other ways people kind of had contact with people who were not their spouses in the past.

Reader Comments