Interview with Doug Holder

After serving in the US Air Force as an aircraft crew chief, Michael Mack worked a variety of factory and labor jobs before returning to school and graduating from the writing program at MIT.

Mack has performed at the US Library of Congress, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Columbia Festival of the Arts, Philadelphia Fringe Festival, the Austin International Poetry Festival, and Off-Off-Broadway at the Times Square Arts Center.

His work has aired on NPR, and has been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), America, the Beloit Poetry Journal, Cumberland Poetry Review, and is featured in Best Catholic Writing 2005.

Mack has also performed at scores of venues for consumers and providers of mental health services, including McLean Psychiatric Hospital, the national conference of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), and for faculty and students of the Harvard Medical School and Yale Medical School.

Awards that he won include an Artist’s Grant for new theater works from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, First Prize in the Writers Circle National Poetry Competition, and an Eloranta Fellowship, which funded a residency at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre for the Arts in Ireland.

Mack lives in the Boston area, supplementing his work as a poet and performer with assignments as a freelance writer.

I spoke with him on my Somerville Community Access TV show “Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer.”

Doug Holder: Mike your mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia right?

Michael Mack: Yes, she was diagnosed when I was five. As you know, it’s a life long commitment not only for the people who have the illness, but also the family. It is the kind of illness that ripples out in many ways.

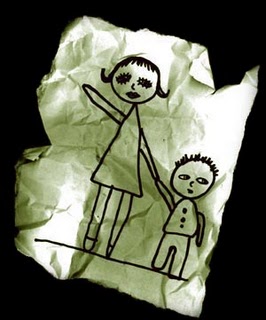

Doug Holder: You wrote a play about your experience with her while growing up titled: “Hearing Voices, Speaking in Tongues.”

Michael Mack: I am grateful to say I performed all over the country with it. When I first started writing it; I really didn’t understand what I was writing. All I know I was writing sketches, poems, about my earlier life. I wrote about Mama, Dad, about how we all were trying to navigate the illness. It was in 1985 when I first scratched out that first line.

For me as a kid to see my mom in the state hospital, heavily medicated with thorazine—well, the term to describe what was being done to her was warehousing. Just give them enough drugs—so the patients won’t give you any trouble.

Doug Holder: You are a versatile artist: Performer, Playwright, Poet. To which role do you identify most closely?

Michael Mack: Everything starts with my spiritual life. I was raised Catholic. I am no longer a practicing Catholic. But the spiritual life is still central. So everything springs out of that. The poetry and the playwriting.

Doug Holder: What do you mean by the “spiritual life.”

Michael Mack: Well, I have heard it said you can leave the Catholic Church, but the Church doesn’t leave you. I think the Church has informed a lot of my life. But I moved on to explore other religious teachings. My poetry accesses that same center the spiritual does. Before every show I invoke the spirit of my late mother.

Doug Holder: If your mother were alive would she feel that you exploited her for your work?

Michael Mack: That is a great question. My dream had been for a long time than Mama would see the show and after I finished she would come up and take a bow. That never happened. She died before that could happen. When I first told her that I was writing about her—that I was starting to perform this show—she didn’t want anything to do with it. For her it brought up a lot of memories that she didn’t want to watch on stage. She started to come around though.

Once I took her to a poetry open mic in Baltimore. We sat down. Poets started getting up to read. She was dumbfounded. It was like she never saw anything like this in her life. For weeks afterward she said: “There is this place you can go in front of a microphone—and say whatever you want and the FBI won’t get you.” From then on I think she was starting to think more positively about seeing the show. Unfortunately—a couple of months later she died of colon cancer—she was 73.

Everybody in the family has seen the show. My father flew up to see me perform it. He sat in the front row. I couldn’t look at him. After the show he said, “ You know son, you spend your whole life with your kids, and you think you know them. And then you see your son doing this and its beautiful.” I’m pleased to say I have the family stamp of approval.

Doug Holder: How was it performing the play in mental hospital for patients?

Michael Mack: I had to take a poetic leap of faith to capture the experience of someone else. When I first performed it in hospitals I was very anxious about that. I am pleased to say the response has been quite positive. Almost to a person, people who have a major mental illness said they appreciate having somebody giving voice to the experience. I would like to see more people with mental illness have an opportunity to give voice to their experience through the arts. I want them to tell us what it is like.

Doug Holder: Why do you think there is so much mental illness between artist and poets? Look at Lowell, Plath and Sexton, for instance.

Michael Mack: I can’t speak as a clinician. People with mental illness, I think, as well as artists, often have a more direct access to those feelings, thoughts, to the dream world. We all have access to this when we sleep, but I am guessing that artists and poets have more access to that dream world in their day-to-day life. The trick is to managing it in the day to day.

Reader Comments