This week’s guest columnist is Somerville Bagel Bard Michael Todd Steffen. Mike is a widely published poet and critic, and a mainstay on the Boston Area Small Press and Poetry Scene http://dougholder.blogspot.com

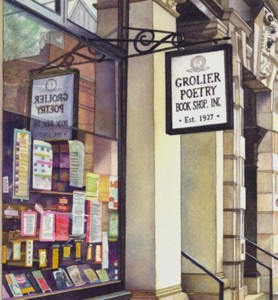

What’s Next in Poetry? –a discussion about the future of poetry, hosted by the Grolier Poetry Bookshop on Friday September 13, with guests Adam Kirsch, Philip Nikolayev, and Marjorie Perloff.

article by Michael Todd Steffen

Marjorie Perloff, retired Florence Scott Professor of English Emerita at the University of Southern California, widely known for her writing on experimental and avant-garde poetry.

Adam Kirsch, senior editor of The New Republic and a contributing editor to Harvard Magazine, has been described by John Palattella as“the offspring of the New Formalists.”

Philip Nikolayev, editor of Fulcrum, an Annual of Poetry and Esthetics, which has included the poetry of Paul Muldoon, John Kinsella, Billy Collins and many others.

Maybe the main point about an unrecorded meet-up in an intimate, iconic space like the Grolier is being there, and the wisest thing to comment about it: You’d have to be there… The event was spirited and to the day, and with renowned critic Marjorie Perloff, as well as her co-panelists Adam Kirsch and Philip Nikolayev, the evening generated vital ideas on the topic, What’s Next? What’s upcoming, what does the future hold for poetry?

Maybe the main point about an unrecorded meet-up in an intimate, iconic space like the Grolier is being there, and the wisest thing to comment about it: You’d have to be there… The event was spirited and to the day, and with renowned critic Marjorie Perloff, as well as her co-panelists Adam Kirsch and Philip Nikolayev, the evening generated vital ideas on the topic, What’s Next? What’s upcoming, what does the future hold for poetry?

Some of the main ideas discussed by the panelists included: How poets evolve from different traditions in poetry to new voices; how our technical-visual-image oriented culture posed a different challenge to poets than the book-word oriented culture of the past before television, movies, pcs, iphones…; what has come to be the standard anecdotal poem prevalently turned out by MFA writing programs and published in the major poetry journals; and the terrible difficulty of discerning which poets among the virtual sea of new emerging poets each year would survive.

On that last topic, Marjorie Perloff noted that while it’s easy for most commentators and anthologists to agree who the major Modernist poets are, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, agreement on the great voices of the ensuing generation (the “models” for today’s poets) has been more elusive, while names like John Ashbury, Frank O’Hara, James Merrill, Robert Duncan, Derek Walcott and Mary Oliver were brought up. The notion of a central tradition for poetry in the English language such as the one Eliot established, beaming back through Tennyson, the Romantics, Pope, Milton and Shakespeare, has given way to a new stable of potential poets from university programs, most of whom are not even familiar with Theodore Roethke.

So far, all is well. A grim outlook, with much to complain about, despair of: these have forever only nourished poets and their rankling, poetry.

Adam Kirsch notably observed that writing and reading poetry in our time has been affected by the consumerist tendencies of the culture. We go through more poetry (that is less carefully written), we go through it faster, and the poems seem to mean less, they are shelved in schools for packaging rather than for contention, scrutiny, debate, genuine dialogue, where wide acceptance of origin is the rule.

Some of the highlight points made by Philip Nikolayev, after much meandering consideration, paradoxically yet convincingly in the broad allowance of the discussion were that there remained a nobility to the expression of true poetry, a challenge of betterment to the self. At the end of the day among those in the practice of the art, Nikolayev offered, there were “poets and non-poets,” which drew many silent nods of acquiescence around the closely felt space in the historic book shop.

Marjorie Perloff engaged the audience in a more specific, animated, and I think very timely talk about Frank O’Hara’s book Lunch Poems upon the 50th anniversary of that book’s publication in 1964 by San Francisco’s City Lights Books. Perloff gave extended attention to O’Hara’s 17-line composition “Poem” (“Lana Turner has collapsed”),significantly pointing out the very human—“trotting”, rushing to meet somebody, weather conscious, fallible “I have been to a lot of parties/and acted perfectly disgraceful”—elements of O’Hara’s language (vernacular) compared to the remote, very technically neutral and uncompromising voice that dominates poetry in the journals being published today. Perloff’s tribute to O’Hara ramified to comments about conceptual poets, using others’ texts in original arrangements, with a fairly direct critique about how censored and cautious today’s poets seem compared to O’Hara and on back to Cummings, Pound and Eliot, the poets who were ready and able to scope out the challenge of their societies’ ponderous expectations of language and to overthrow those expectations necessarily to emerge as new meaningful voices. This doesn’t seem to be happening today, whether due to its failure by the poet at the page or by editors unwilling to take risks beyond current standards.

One of the hopes offered in the course of the evening, I thought—and no two accounts of this discussion could possibly be the same—was Kirsch’s observation that while new scientific (and technological) breakthroughs supplanted and to an extent obsolesced those of their predecessors, the cycles of human experience, witnessed especially by poetry, in the songs of words and their arrangements, although successive and changing, were renewably meaningful. We still read Homer and Sappho and find much insight, inspiration and pleasure that cannot be substituted by reading, say, Robert Pinsky and Louis Gluck, wonderful and plentiful as their poetry is. The mark of great poets is indelible. Pertinently and plainly, Nikolayev reiterated that the viable poet of today heading for tomorrow had to be “steeped in poetry,” a nearly amorphous vast reservoir of the past constantly attracting addition and alteration.

I think everybody present would want to join me in thanking the guests for their very considerate thoughts, and to thank Ifeanyi Menkiti, his wife Carol and Elizabeth Doran for organizing the event at the Grolier, “the oldest continuously run bookshop in the country.”

Reader Comments