Our guest reviewer this week is Tom Miller. Miller is a Somerville Bagel Bard – a history graduate student at Salem State University, and a retired auto industry executive.

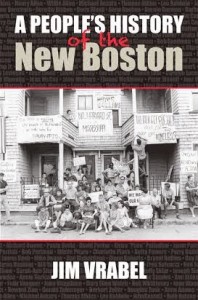

A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF THE NEW BOSTON

A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF THE NEW BOSTON

By Jim Vrable

University of Massachusetts Press

Amherst and Boston 2014

235pages

Review by Tom Miller

“Boston, today, is seen as one of America’s best cities-one that works for its resident, generates jobs, welcomes visitors, remembers its past, and embraces its future… Credit for building the New Boston usually goes to a small group of “city fathers”… But that is only half of the story…” So starts a book that is a story not so much about what happened as what did NOT happen and WHY it did not happen.

Like many Northeastern and Midwestern cities in the aftermath of the mobilization for World War II, Boston fell into at least stagnation if not decay in the 1940s and 50s. Spurred by federal programs to revitalize the cities, most notably Urban Renewal, Boston leaders in both the public and private (for profit) sectors set forth an ambitious if not totally coherent plan to remove the blight of poor and run down areas in the city. Their vision was to replace them with grand buildings and expressways creating a “world class” city focused upon a dynamic and vital city center while essentially ignoring if not removing the contiguous outlying areas of the rest of the city. Jobs and growth. Jobs and growth were the mantras. And credit must be given to these initiatives for Boston having become what it is today.

However, this transition from the “Old Boston” to the “New Boston” as Jim Vrabel defines then versus now was not without difficulty. The fact that Boston is a livable, vital and caring place to live and work lies as much in the hands of those who spoke out against overbearing government and private interest groups. These entities were so focused on the material results that they gave little if any concern to the effect upon those folks who resided in the various communities and were in fact the heartbeat of the city.

As Vrabel notes, Boston was a conglomeration of neighborhoods that were not necessarily insular but nonetheless were culturally unique within their somewhat loosely defined boundaries. Most were blue collar to middle class. Some were ethnic. Some were minority. Each had developed an individual sense of community and pride in that community.

In the rush to construct the New Boston, these communities were never considered in any fashion other than as objects to be overcome and thus the people who lived in them were never consulted about what was to take place and how it might affect them.

The essential if not intended thrust of Urban Renewal was to remove blighted structures and replace them with modern ones. In most plans it was a given that there would be fewer living units (and more expensive ones) than what had existed previously, but little if any concern was expressed about what was to happen to those families who were displaced in this transition. Where would they live? No one seemed to care.

The obliteration by Urban Renewal of Boston’s West End neighborhood was the opening salvo in this campaign and it served as THE wake up call to all the other neighborhoods in Boston. From this action came awareness. From awareness came reaction. And from reaction sprang the rise of the activists of the 1960s and 70s which forced governments – city, state, national – to become accountable and concerned.

Mr. Vrable has very skillfully detailed the complex currents of events that occurred often in concert with one and other during this tumultuous era. Quoting interviews, scholarly works, news reports and other sources he manages to walk us through a very intricate fabric of the causes and manners of ordinary peoples’ reactions to how decisions made by others affected their lives and what they did about it. He names names. He defines the dozens of community action groups that arose, who led them, what successes and failures they had. He takes to task some leaders of government, particularly mayors and their designees, and city and state agencies as well. But he also gives credit where credit is due.

In his final chapter Mr. Vrabel states, “The New Boston has come a long way from the Old Boston, but all this progress didn’t come about by accident. For the last sixty years, the city has benefited from having capable leaders (particularly mayors), strong institutions, and the imagination and nerve to strike off in new directions. But it also benefited – in the 1960s and 1970s – from having residents who refused to just follow along.”

Neighborhoods, expressways, jobs, schools and busing, Viet Nam and a variety of other issues, including The Public Garden, caused activism and organization at a grass roots level within the city. In 22 chapters and 235 pages Mr. Vrable touches on them all. This book is not intended to be a definitive study of any particular group, cause or effect but rather to give an introduction and an overview of what happened in Boston in a specific time when ordinary citizens chose to be heard. And not only to be heard but to participate in decisions that were being made that would affect their lives and communities. Their actions in combination have had perhaps the most significant effect in how Boston has come to be the city that it is today. As such the book serves as an opening door inviting a more in depth study of community dynamics and should be of particular interest to community planners, sociologists and historians.

Reader Comments