Ah! Ain’t love grand! Yes grand, tragic, maddening, evolving… in all its infinite variety. Feldman in his collection Immortality explores love and its many manifestations, as well as other themes. I had the privilege to interview Feldman on my Somerville Community Access TV show Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer recently.

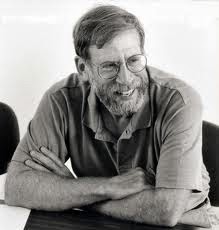

Poet Alan Feldman

Alan Feldman’s A Sail to Great Island (2004) won the Pollak Prize for Poetry from the University of Wisconsin. The Happy Genius (1978) won the annual George Elliston Book Award for the best collection published by a small, U.S. non-profit press. His work has appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, the New Yorker, and Kenyon Review, among many other magazines, and included in The Best American Poetry 2001 (edited by Robert Hass) and BAP 2011 (edited by Kevin Young). Feldman’s recent work appears in Hanging Loose, Cimarron Review, upstreet, Southern Review, Yale Review, Salamander, Southwest Review, Cincinnati Review, Catamaran, Worcester Review, and online in Boston Poetry Magazine and Cortland Review. His poem “A Man and A Woman” was featured in Tony Hoagland’s 2013 article for Harper’s, “Twenty Little Poems That Could Save America.”

Feldman was a professor and chair of English at Framingham State University, and for 22 years taught the advanced creative writing class at Harvard University’s Radcliffe Seminars. He offers free, drop-in poetry workshops at the Framingham (MA) public library near his home.

Doug Holder: We were both born in New York City, and moved out to the suburbs of Long Island. I always found the suburbs stifling–how did you find it?

Alan Feldman: I was desperate to get out of the suburbs. But I will tell you something about Woodmere, L.I where I grew up. My mother and Louise Gluck’s mother were best friends. Louise grew up in Hewlett and I grew up in Woodmere and so apparently it was a fertile ground for poets. And Louise had an exhibit of her paintings at the Hewlett library when I was in high school. Her paintings were striking. Later -I met her on a bus when I was attending Columbia University. She told me she was taking a very good poetry course with Leoine Adams.And Louise was very beautiful, and so I thought I would sign up for the workshop, and maybe get to know her. But the workshop was not for me so I stopped going. But I forgot to drop the course. So my transcript will show the only course that I took in poetry writing, I failed.

My parents were both teachers and they took me and my sister to Europe for three months in 1952. I remember vividly when we were in Rome, I saw the Protestant Cemetery where Keats and Shelley are buried. It was an experience I will never forget. Here we were visiting the graves of folks long dead and we didn’t know personally. I was all of seven years old. Shelley’s grave was very well-tended–he came from a well- to- do background. It was covered with ivory. and Keats’ grave was essentially bare. And then I remember my mother crying at Keats’ grave. I thought:”How could something like this affect a living person?” This planted the idea in my soul that there is a transmission from the dead to the living via poetry. This … I believe… was a big influence for me becoming an artist and poet. So Woodmere was my home–but it was my particular home and family.

DH: You taught in the South Bronx in the late 60s. That must of been–to say the least–challenging..

AF: It was incredibly difficult. I had a choice to teach or ship out to Vietnam. I think I chose the wrong thing ( Laugh) I was placed in a special services school. This was where the average sixth grader was reading at a third grade level. A third of the staff were brand new-and had never been a teacher in the classroom. I was terrible at it. After the first half year they took me out of the classroom and made me a specialist in Language Arts and Science. I got to teach the same lessons all day long–so I got to learn how to teach. The second year they gave me class 5-1.This class had kids who scored the highest in the math test. They were like little geniuses. Some of them were were reading way above grade-level. And we put on plays and I had them painting. I think I succeeded here. But the idea that you can drop a bright and educated person in the classroom and they can automatically teach is wrong. There is so much technique in classroom management. I wasn’t ready to teach kids whose main issue was to stay in their seat.

DH: You sent me some poems from your collection Immortality. Many of the poems deal with the psychology of love. One of the poems is titled ” The Rowboat, The Girl, The Light” This poem took place when you were very young. You were out on a rural lake and a young girl swam to your boat. Everything smelled of pine, desire, things were elemental. Now you have gotten older things have changed in this realm. Things are more urgent–there is a deeper appreciation of the world.

AF: As you get older-and I will be 70 soon–your desire becomes generalized. You desire the world and everything in it–as a child you take that for granted.

DH: Your wife Nan Hass is an accomplished artist. Do you guys collaborate?

AF: We understand each others’ obsessiveness. We are both infected with this need to make art. Nan works all the time and has an incredible drive. She understands me. If something you are working on gets a hold of you–you are going to be immersed in it. We both give each other space. We are hilariously bad at collaboration. We worked on a book of poems, my poems and her illustrations. We got into such a fight about the binding that it almost destroyed our marriage. (Laugh) So our collaboration are limited and with parameters.

DH: You were a professor at Framingham State University for many years. In your opinion what makes for a good teacher?

AF: A really good knowledge of the subject. A love for the subject. A strong desire to be helpful. A sense of organization. I have observed so many shapeless classes. The essential purpose is too vague.

The Rowboat, The Girl, The Light

Today the pool is pierced

by sunlight, and there’s a girl

in my lane, her flesh lit

by reflected light from below

to a subaqueous brightness

the way the water in our boathouse

(demolished long ago)

shone in our faces.

We would lean over to see the striped

shadowy fish, their sides

glinting like belt buckles

or dimes, and the wood

smelled ancient and dry,

and probably the dock

creaked, as my row boat

thumped against it,

the boat’s floor resounding

like a drum when we stamped.

Unsinkable because of

compartments under the seat

like little ovens, so I could

go out alone, provided

I stayed in the cove, our point

in the star-shaped lake,

and hewed close to the shore

I wouldn’t have wanted to leave

anyway, because she lived there––

an unfathomably pretty girl,

like the Queen of Heaven.

On the best days she would hail me

from her landing, but once

she jumped in, and swam to me,

her white body dripping

as she clambered aboard.

Then everything smelled of pine.

I think that’s how desire felt then––

like an odor, the pines

that covered the hillside

above her house.

Desire these days feels like desire

for everything. The air

I strain to breathe, the white

clouds rumbling across

the blue outside the pool’s

picture windows, and the little

pinpricks of light

on people’s fenders

while the traffic passes.

Alive! Alive! each stroke

like the clenching of the heart

Reader Comments