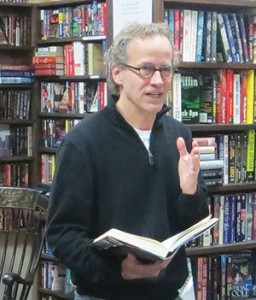

Author Dick Lehr sheds light on one of the most notoriously dark figures in the world of organized crime. – Photo by Blake Maddux

By Blake Maddux

“I think it’s the job of a biographer to also get at the ‘why?’ and the ‘how’ all this happened,” author Dick Lehr said during his appearance at The Book Shop last week. “The ‘why’ of the Whitey, the making of this monster, digging into psychology and other factors influencing the emergence of someone who’s now, in my view, a historic crime figure.”

A former reporter, Lehr spent almost 20 years at the Boston Globe and is now finishing his ninth year as a journalism professor at Boston University.

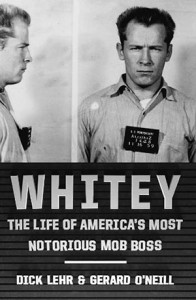

His latest book is Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss. It is the third book that he has written with Gerard O’Neill, another erstwhile Globe reporter. The two first previously collaborated on Black Mass: Whitey Bulger, the FBI, and a Devil’s Deal (2000) and The Underboss: The Rise and Fall of a Mafia Family.

Lehr said that one of the main motivations behind his and O’Neill’s decision to pen a full biography of James Bulger was that “in 1975, when Whitey Bulger cult his deal with the FBI, he was already 48 years old. He lived, in a sense, a half a life already when that stuff began. Very little [was] known or written about that first half of a life, those first 48 years.”

Throughout his 35-minute talk, Lehr made the point, sometimes more implicitly than explicitly, that the White Bulger saga is much more than a local story.

He reminded the audience that Bulger was arrested in June 2011, the month following the killing of Osama bin Laden. Therefore, “at that moment in time, [Bulger] had replaced Osama Bin Laden as top dog on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list.”

Moreover, Lehr declared that “history’s going to show that he is one of the most notorious and major crime figures of the 20th century.” He attributed this to Bulger’s “body count” and longevity.

According to Lehr, “He’s charged with 19 murders either that he committed by himself, with his own hands – he was a real hands-on killer – or that he ordered committed. But if you talk to any investigator who’s been tracking this guy over the years, there’s more than 19.”

This lead Lehr to conclude that Bulger “can match body counts with any kind of crime figure that rolls off your tongue: John Dillinger, John Gotti, Bonnie and Clyde.”

Finally, Lehr asserted, “is that when you say ‘Whitey Bulger,’ in the same breath you have to say, ‘the FBI.’ He managed to do what I would say no other crime boss or crime figure has ever been able to do: he turned a crew of agents in the Boston office of the FBI into his own palace guard.”

As a result of this connection, Lehr said toward the end of the question and answer portion, ““When it comes to Whitey Bulger, the FBI has no credibility.”

Lehr focused his talk mostly on Bugler’s time as a prisoner in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Despite numerous prior arrests, Bulger did not end up in jail until 1956, when he was sent to the Atlanta Penitentiary at age 26.

These three years may very well have been more interesting than the two that he later spent at America’s most storied prison, Alcatraz.

In Atlanta, Bulger did not acclimate well to living in a cell that housed a total of eight prisoners.

“The record of his first few months is so un-Whitey Bulger-like,” Lehr explained. “It’s a deer caught in the headlights. He’s a control freak and he was with seven other inmates who were invading his space and time. Within two months he checked himself into the psych ward. He was having a breakdown. He couldn’t handle it.”

The excerpt that Lehr chose to read from Whitey dealt with the LSD Project that doctors from Emory University conducted and in which Bulger participated.

The excerpt that Lehr chose to read from Whitey dealt with the LSD Project that doctors from Emory University conducted and in which Bulger participated.

Reading directly from the book, Lehr said, “Whitey Bulger had always felt most secure when in control, but prison had changed all that. He lost nearly every measure of control. Hallucinating on LSD meant losing even more. He took 50 trips over the course of a year and a half.”

Bulger arrived at Alcatraz in 1959. Thanks to his connections with John McCormack, a South Boston native who was also Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Bugler spent only two years at Alcatraz before being transferred to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

“The average stay for an inmate in Alcatraz was eight years,” Lehr said. “That’s the special treatment he got.”

The 15-minute question and answer period opened with a query as to whether President Barack Obama was aware of his part in the capture of Whitey Bulger.

After initially joking that the President did not return his calls, Lehr told of how the FBI knew to take the tip from a woman in Iceland seriously because she pointed out that the man whom she knew as Charlie Gasko responded with disgust to her elation over Obama’s election.

“Whitey, or Charlie, essentially pulled a nutty on her,” Lehr said. “He couldn’t believe that she thought that was a good thing, and so that whole racist side of Whitey came out. The fugitive task force knew that Whitey was a racist. He believed that the races should be separate and things like that.”

A young man in the audience told of how his mother received a call from a friend who was on vacation in Santa Monica. The woman frantically claimed to have seen Whitey Bulger, only to be told by the young man’s mother, “Don’t be ridiculous. Why would he be there?”

For the final question, an even younger man, probably in his early teens, asked if Lehr thought that the LSD that Bulger had taken as part of the inmate study “was a contributing factor in creating the monster.”

“He was already a monster when he went in,” Lehr answered.

Reader Comments