I was a founding member of the Wilderness House Literary Retreat started by Steve Glines in Littleton, Mass. Although the retreat lasted only a few years I got to interview and write about a lot of interesting folks. Here is one of them.

An afternoon with the Atlantic fiction editor.

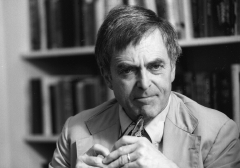

The Wilderness House Literary Retreat Hosts Atlantic fiction editor C. Michael Curtis.

On a sweltering early summer morning Somerville poet Linda Haviland Conte and I were ferried by golf cart up a long and winding forested hill to the “Wilderness House Literary Retreat,” in Littleton, Mass, to spend the day with C. Michael Curtis the fiction editor of “The Atlantic” magazine. “The Atlantic” is moving from its long-time home in Boston to Washington, D.C. It will now be publishing its fiction and poetry in one large annual issue; rather than individual issues. C. Michael Curtis, who will edit this annual, gave the group in attendance a sneak preview of the issue and an illuminating discussion of his life in the rarefied environs of the literary world.

Curtis was peppered with many questions from an inquisitive audience. He was asked about his relationship with late poetry editor of “The Atlantic,” Peter Davison. Curtis met Davison in 1961 at CornellUniversity when Curtis was a student. It seems that Davison was in town for an Anne Sexton reading. Curtis managed to arrange a dinner meeting with Davison. He showed him a few of his poems, and the poetry editor took them back to Boston. Favorably impressed, Davison offered Curtis an intern or as it was called then a “summer reader,” position. This led to Curtis’ long affair with The Atlantic. He left Cornell just shy of his PhD, and never went back. Curtis remained friends with Davison over the years in spite of breaking Davison’s rib in a touch football game one Cambridge afternoon.

In his long career at the magazine Curtis has edited the works of many notable authors. On one rare occasion he had to tell John Updike that one of his pieces “didn’t work.” Fortunately Updike was in agreement. A young John Sayles, (the noted indie filmmaker), was very offended by some minor changes Curtis made in his manuscript. It seems that Sayles had substituted dashes for quotations. Curtis naturally changed them back to standard quotes. Sayles took strong exception; telling Curtis that he does everything for a reason. Sayles was ready to withdraw his work. Curtis left the dashes in.

After a hearty lunch with retreat participants, Curtis talked about what he looks for in a manuscript. Since “The Atlantic” gets up to 12,000 submissions a year, quick decisions must be made. Curtis said there are a few things that will undermine a writer’s chances. Misspelled words, bad grammar, adjectives in front of every noun, putting words in caps, overuse of the ellipsis, and the use of the present tense. Curtis feels that the use of the present often makes the work seem affected. Curtis said that in the cover letter that accompanies the manuscript the writer should never explain his story. This is a sure mark of an amateur. A good writer will realize the reader will discover this on his own. Oddly enough Curtis has received manuscripts that included a number of rejection slips from top shelf magazines. This, he said, is a poor advertisement for a writer’s work. Curtis also made it clear that he is not impressed by trendy writing. But he always likes to see well-constructed and coherent sentences. He also looks for an authentic voice and authentic dialogue in the work he reviews.

Curtis believes that an editor can make enormous improvements to a book. Curtis works on the grammar, syntax, and transitions in a story so it will flow. However, he is careful not to edit out the “voice’ of the writer. He feels that it is possible we may never know the true voice of authors like Thomas Wolfe, who was heavily edited by Maxwell Perkins.

For the aspiring writer, Curtis is strongly in favor of MFA writing programs. He said: “A lot of the stuff we publish comes from writers in MFA programs. Writers in MFA programs are the ones who are going to stay with it.”

As Linda and I left the retreat, we were met by a group of wild turkeys that had roamed on to the grounds. Perhaps they heard about this literary talk. After all, I’ve heard it said more than once that “Literature is for the birds.”

Reader Comments