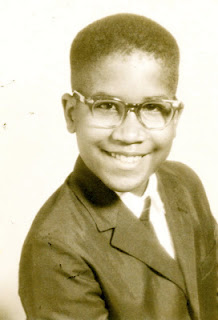

Afaa Michael Weaver.

I asked poet Afaa Michael Weaver how he would define himself or like to be remembered. He told me: ” The kid Michael from Federal Street in East Baltimore with the funny looking glasses and big wingtip shoes. He grew up to write poetry”. And indeed Weaver, 60, has written poetry, plays, essays, and is currently working on a memoir. This longtime Somerville resident is an English professor at Simmons College in Boston, a winner of the prestigious Pushcart Prize, a winner of the New England Poetry Club’s Mary Sarton Award, an NEA, not to mention the Ibbetson Street Press Lifetime Achievement Award, as well as many other accolades.. His papers are now archived at the Howard Gotllieb Archival Research Center at Boston University. I talked with him on Independence Day at the bustling Bloc 11 Café in Union Square, Somerville.

Doug Holder: The last time we touched base was probably in 2010. What has been happening?

Afaa Michael Weaver: I had a book of poetry translated into Arabic. The translator’s name is Wissal Al- Allaq. The title of the book in English is “Like the Wind.” They are mostly original poems I wrote for the Kalimah Project. It is a project based in the United Arab Emirates. They publish, in their words: “Significant contemporary work.” Wissal-she is a good translator. The book itself is beautiful looking—and it is in hardback.

DH: Any books in the works?

AMW: I signed a contract in 2011 with the University of Pittsburgh Press. The book is titled: The Government of Nature. It concerns childhood, and spirituality. The title refers to the Daoist metaphor of the interior of the body being a microcosm of the external world. The world of nature exists in the interior of the body.

DH: You are fascinated by Chinese culture and literature. You started the Simmons College International Poetry Conference several years ago. How is it going?

AMW: The structure is there but no money. I may try it again in another year or two. I want to get my memoir done. That’s what I am working on now.

DH: What gave you the impetus to undertake a memoir—turning 60?

AMW: I turned 60 last year. People have been asking me to write one. They say my past is unusual. I have worked in a factory, a warehouse, for many years, and at the same time I wrote for The Baltimore Sun.

DH: Don Aucoin of The Boston Globe described you as a Poet Forged in Heartbreak.

AMW: I was from a poor, poor working-class background. I worked 15 years in a factory as a laborer. I was diagnosed with Congestive Heart Failure in 1995, and that June I was admitted to a cardiac unit. They gave me 5 years to live. That’s when my book Timber and Prayers came out. After that I started to confront my abusive childhood. I had three marriages and three divorces. In the first marriage I lost a child. That was bad—I had a complete nervous background. The child had Down Syndrome. I dropped out of the University of Maryland after this and worked in a steel mill. I was in the military. I was a cook for military intelligence. I was never deployed. But basic training breaks you down, my child died, and I was all of 19 years old. Things like this happen to young veterans today. I have a number of veteran students that I teach at the William Joiner Center at UMASS Boston every summer. I want to support them as much as I can.

DH: Do you have a publisher for your memoir?

AMW: I have a few people who are reading it. Poets Martha Collins and Danielle Georges are looking at it. I hope to turn into my agent before I go back to teaching.

DH: I know you live in Somerville, right up the block from me. You refer to it as the cave.

AMW: I live directly across from city hall. The house is actually built on a hill. So I live in a cave of sorts. It is modest. Very Zen-like. It is affordable. I was traveling back and forth to Taiwan and China so the low overhead allowed me to spend money for airfare. Every trip I take there is out of my own pocket. I like living in Somerville more than I did than when I first moved here in 1997. It is more diverse and cosmopolitan. It was a little hostile when I first moved here. Union Square was dead before but now it’s alive…it has an Asian Grocery, an Indian Market, Sherman’s, Bloc 11 Café, etc…

DH: I know you studied playwriting at Brown University. Have you written any theatre pieces as of late?

AMW: I haven’t written a new play in quite a while but I really want to get back into it. I got my MFA from Brown. When I went there with my poetry book and a NEA, I met George Huston Bass; who was literary secretary to Langston Hughes. He and Paula Vogel talked me into playwriting. They thought I had talent as a playwright. I was anxious to try. So when I came out of graduate school I had two professional productions in 1993. I got glowing reviews in Philadelphia and in Chicago. At that time I had better luck with my plays than my poetry. My first play was named Rosa. It concerned a Blues singer in Ohio—it was a love story. The director was Trazana Beverly. She is the first African-American poet to win a Tony Award. She won it for her role in For Colored Girls…” In Chicago I won a PDI theatre award. But my life in theatre sunk my third marriage. The theatre is a funny world. You have to know yourself—a good playwright knows himself. When I was at Brown University Paul Vogel was just starting her play writing program. I was one of her first students. Lynn Notage was another student. Two or three years ago she went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for her play Ruins. I was close with Vogel. We both shared an abuse history. I think she believed in me more as a playwright than a poet. After my marriage broke I retreated into poetry. After this experience came my collection Talisman.

DH: You are now in the older generation of African American Poets. I was reading about the generation after you in Poets and Writers magazine, the Dark Room Collective. How does the younger generation of poets differ from your generation?

AMW: They are all in their 40’s now. The original Darkroom was peopled with such poets as Kevin Young, Major Jackson, Thomas Sayers, Natasha Trethewey ( Now U.S. Poet Laureate), Danielle Georges, Patrick Sylvan, Sharon Strange and others. When I was coming up we did not have a collective. I was very influenced by Lucille Clifton. In Baltimore, Andre Codrescu introduced me to Surrealism. I was also influenced by Baltimore poets James Taylor—no, not the singer!—and John Strasburgh, a fiction writer. The Darkroom Collective was all black. The people I cut my teeth with were all white. Melvin E. Brown was the only other Black poet I knew. Baltimore, back in the day was centered around Codrescu. I was basically the only black poet.

DH: How about the African American writers’ organization Cave Canem that you were involved with?

AMW: I started out on faculty at Cave Canem with Elizabeth Alexander. I had a falling out with Cave Canem and I resigned. They asked me to come back as the first elder. Later I asked that Lucille Clifton to be a second elder. I am always there for Canem fellows. I never deny them.

DH: How would you like to be defined—remembered?

AMW: The kid Michael from Federal St in East Baltimore, who used to wear funny glasses and big wingtip shoes. Later he grew up to write poetry.

DH: That’s you?

AMW: It is Doug, it is.

Reader Comments