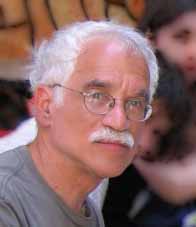

Bernard Horn is the author of the award-winning poetry collection “Our Daily Words.” This English professor at Framingham State University in Massachusetts has had his work praised by the likes of Robert Pinsky, and David Mamet. Irene Koronas, a reviewer for the online journal “Boston Area Small Press and Poetry Scene” wrote of his work:

“ We read each poem in the collection, because, it considers how far we dig to find a complete sentence, one that holds the earth, our experience, our dreams, then when the sentence ends, we feel complete, and only in a poem lies our daily refreshment.”

Horn’s poems and translations are widely published, in such journals as “The Manhattan Review,” “The New Yorker,” “ The Worcester Review,” and others. Horn has taught at Haifa University in Israel and at the Radcliffe Seminars at Harvard University. I spoke with him on my Somerville Community Access TV Show “ Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer.”

Doug Holder: “Our Daily Words” is your first poetry collection and you have had a long and distinguished career. What took you so long?

Bernard Horn: I have been writing for a long time–it’s a matter of the market. I have been in writing groups with people for years and I have been sending out poems for many years. I am slow at writing poems. It is a longtime between how a poem ends and begins, not to mention all my teaching and family responsibilities that takes away from writing time. However I get material from my family. A lot of my poems are about family. I have written a number of poems in the middle of family chaos.

DH: Your wife is an artist and recently retired from teaching at Endicott College. Does your work compliment or overlap each other?

BH: We just had a joint presentation. A bunch of my poems were written in 2001 in Israel when I was teaching at Haifa University. At the time my wife ( Linda Klein) was doing these small gouache paintings. My poems dealt with terrorism–with the Second Intifada–as it was known. We didn’t think there was a relationship between her paintings and my poems. But after looking closely at them I realized gouache looks like you are looking through a screen or veil at an object on the other side. Sometimes it looks like you are looking through barbed wire. I realized that even though I knew Israel fairly well, I was still looking at i through the ‘veil’ of being an American. Later we put these images in my poetry collection. We had a joint exhibit at the Marblehead Public Library. This was the first time we did this.

Both my wife and I know as a painter and a poet respectively, that the moods we go through don’t necessarily have to do with the ot her person. It is a valuable thing to know in a relationship.

DH: In your new collection you have a poem titled ” The Smell of Time.” As soon as I smell ethnic food like gefilte fish, I am transported back in time to the early 60’s when I was a boy at my grandmother’s house in the Bronx. I wonder, if one doesn’t have a sense of smell, could one still be a good poet?

BH: That’s a terrific question. Memory is so bound up with smell. And my poems are so dense with memory. It is such a powerful thing–and at times more than anything else it tells you time passes. Place and memory are just as important; so it is a hard question to answer.

DH: You seem to work hard to find that sentence that captures our dreams, our experience,… our essence.

BH: I am always taken with the power of a sentence rolling forward. It is a memory of a sensation, on top of a thought.

DH: You have translated poems of the famous Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. I read in an interview in The Paris Review with Yehuda that he believes all poetry is political. Poems are human responses to reality and politics is part of reality.

BH: I agree. There is a pressure in politics. When I was in Israel my poems were taking in the issue of terrorism. Then I found it hard to write my own poetry. What happens if you are writing during a time of terrorism people always call on you for solidarity. A place of solidarity–it is not a quiet place-it can be a very hard place to write in.

DH: You started out as a chemical engineering student at MIT, but you ended up as a PhD in Literature. How did you get to point A to point B?

BH: Well I think people who knew me were less surprised than anyone else. You just didn’t major in the humanities at MIT. A friend’s theory is that anyone who came of age during Sputnik–and were in sort of the middle between the humanities and the sciences chose the sciences.

This was in the early 60’s, and I started out as a chemical engineer in West Texas. I tied to imagine myself in this job 10 years in the future. I couldn’t. The rest is history.

To My Wife

Some times

when we grab an hour of love

luxuriously in the late afternoon,

the growly baby snoring in the next room,v her sisters at the mall,

I feel as if I’m robbing the gods, who have,

some say, all the time in the world.

–Bernard Horn

Reader Comments