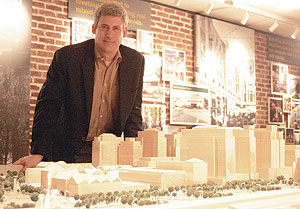

FRIT’s Senior VP of development Don Briggs is bullish on Assembly Row growth.

Briggs talks development at Assembly Square

By Andrew Firestone

The question is still on everyone’s mind here in Somerville: when is the smart-growth multi-use wonderland Assembly Row by the Mystic coming?

Sooner than we think, possibly.

Developer Federal Realty Investment Trust (FRIT) says they will break ground on their first block of the $1.5 billion development in Q1 of 2012, bringing to fruition the public-private partnership for the development of vacant Assembly Row. In May, Somerville Aldermen approved a $25.75 million bond as requested by the state in exchange for funding for the Orange Line, sealing a Tri-Party agreement between FRIT, the city and the commonwealth.

This cemented funding plans for the Orange Line, which included FRIT contributing $15 million to the $50 million transit project. The municipal bonds were used to pay for roads and a storm water drain needed for the construction, and allow the city to reinvest tax revenues back into the development. The tax revenues generated from FRIT’s development are expected to cover the annual $1.6 debt service and more.

The Orange Line is now under construction. Preliminary designs presented to community members were received favorably at a public meeting two weeks ago. There were a few questions about parking, but the plan was otherwise praised.

With transit-oriented development realized, said Senior VP of development Don Briggs, the time for real growth can begin, and with it, the first three buildings.

“Without that, all the work that we had done and all the opportunity that was right there on the doorstep would not have been able to get done,” said Briggs, who had overseen the expenditure of $110 million before the vote was even made. At the time, Briggs feared nothing would come of the development, and said that FRIT would consider leaving the project. “Now it’s just ‘when are we going to get going?’”

“We’re off to the races,” he said.

Briggs recently unveiled his strategy for the first phase of retail stores, which is currently being planned in conjunction with residential partner, developer Avalon Bay of amounting to a total of 420 rental units and 280,000 sq. ft. of retail space. FRIT has been looking to entice bargain outlet stores, as many as 30 in the initial phase and 50 in total. Called a “bold strategy” by the Boston Globe’s Casey Ross, the move signifies FRIT’s confidence that retailers will move their outlet stores closer to the population of their consumers.

It is a wholesale change in mixed-use urban development that Briggs sees, and perhaps, a change in the entire culture of urban planning, as unorthodox as the agreements between corporation and government that first allowed it to take place.

“[The city and commonwealth] have a lot of confidence in our ability to execute, so now it’s up to us to execute,” said Briggs.

FRIT is a realty estate investment trust (REIT), which means it does not pay federal taxes as a corporation, but must give out 90 percent of its taxable income to its shareholders in dividends. Owning 18.6 million sq. ft. strategically located in the most prime real estate markets in the country, FRIT has become a model in the industry, raising their dividend rates 44 consecutive years. They currently have a market cap, or stock price multiplied by number of shares, of $5.4 billion.

However, FRIT does not usually take the role of developer. They, like many REITs, usually lease out properties that they own. While their chief talent has been for successfully operating shopping centers, the Assembly Row development is a change in their usual mode of operation, though they have one other similar development in Bethesda, Maryland outside Washington DC.

While the beginning phases include mostly the retail, with shops and restaurants as well as a multiplex cinema, Briggs describes a “holistic” approach to building a new popular urban center. Beautification and landscaping of parkland, with a fish pier and adornments like statues, will contribute to the eventual planned 1.75 million sq. ft. in R & D/ commercial / office space, 1.13 million sq. ft. of retail (including IKEA) and 2,100 residential units.

“We take land that we own that is suburban in character and context and we turn it into high-density mixed-use development,” said Briggs. “What we are developing is fairly complex developments that require a lot of upfront capital, require a pretty sophisticated skillset.”

Somerville’s Assembly Square fit FRIT’s desire to have “a product type that is where we think is where the country is going over the next 50 years, which is urbanizing transit-orient development,” which he qualified as a high-risk, high reward proposition.

These risks are manifold. While city planning has applauded the transformation of Assembly Square into a 24-hour residential, office-space, shopping, entertainment center, moving from planning to construction has been tarried since FRIT purchased the 45-acre plot in 2005.

The entitlements that FRIT was granted at the site were heavily scrutinized. FRIT agreed to pay the $15 million for the Orange Line in 2006, because of a series of lawsuits regarding zoning violations by community members in the Mystic View Task Force. IKEA’s dalliance in breaking ground compounded issues involving the I-Cubed grant the development received, necessitating the intricate funding plans that brought forth the Tri-Party agreement.

After it was signed in May, Briggs said he “breathed a sigh of relief.”

“Now we’re at the point where we’re through all these hurdles, and we’re going to invest real money in construction and development,” he said. “We are creating a vehicle for growth. We’re through the risk period, and now we’re onto the development and implementation period. Everybody says that construction is really risky, and it is, but not as risky as it was until we got the T-stop,” he said.

Construction and development carries its own risks as well, said Briggs, but they are not as grim as previous. “Can we lease it for what we thought we could lease it for,” asked Briggs for example. “Can we build it for what we thought it was going to cost?”

“We are comfortable that we can,” he said. “We are through a lot of the uncontrollable risks, and we are now into the quantifiable and presumably controllable risks.”

Briggs said that the development opportunities, like the uses for the site are manifold. Technology entrepreneurs and financial services companies that wish to locate near their employee base can choose Somerville for its growing population of college-educated young professionals.

“In the case of something like this, when you are trying to bring all those uses together, managing the risk that all those markets are going to be in sync, and you can see today that they are not quite in sync,” said Briggs. “The residential multi-family market is off the charts. The retail market for the product that we’re doing is strong,” he said, referring to the outlet store plan, “but if we were doing a different retail product it might not be strong.”

As far as office space and research and development tenants were concerned, Briggs was optimistic that Somerville’s location near the Boston entrepreneurial sectors such as Kendall Square and Downtown would ensure that, once buildings began to rise from the barren field, there would be more interest in the fledgling development.

“The office market is just now starting to hopefully become something, it’s still not there yet,” he said. “We don’t know that it will be there yet. It may be another five or 10 years before. Could be that we go through a cycle in the office where it’s taking of existing space and there isn’t a whole lot of new building.”

Reader Comments