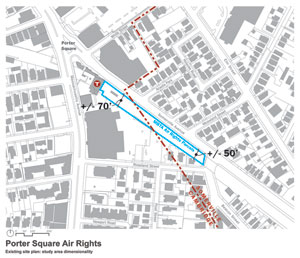

Map of the area considered for the over-the-tracks development.

MBTA considers selling air rights over Porter Square commuter rail tracks

By Ashley Taylor

Owning a parcel of land is part of the fabled American dream. How about owning a parcel of air instead? Air is less expensive and more plentiful than land. The problem is, it’s a bit of a fixer-upper: in order to build a structure on your plot, you have to first build a deck.

Buying air rights instead of land is something developers may have the opportunity to do in Somerville.

For the second time, the MBTA is thinking of soliciting bids from private developers for the right to construct buildings over the commuter rail tracks at Porter Square.

Such a development would require building a deck over the trains, then constructing a building on top of that—without disturbing the smooth operation of the trains.

At a meeting last Tuesday, May 24, Somerville residents, city planners, and transit design specialists discussed that possibility. Tim Love, of the design firm, Utile, and Greg Dicovitsky, of Transit Realty Associates, the MBTA’s real estate manager, presented the history of the project and the current ideas for an over-track development. The presentation made clear that the technical constraints of building over an existing track with set dimensions and the financial limitations of an inherently expensive project dictate certain aspects of any development. Whether or not that development materializes is another matter.

The stretch of train track under consideration runs along Somerville Ave. from the Porter Square T station East to where Beacon Street crosses the train tracks to meet Somerville Ave., then continues for about another block. Currently, a chain-link fence lines the sidewalk along the south side of Somerville Ave. to protect pedestrians from into the 16-foot trench and onto the tracks.

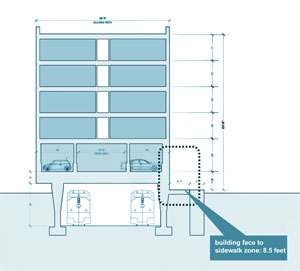

Building section: Creation of building setback and “Flex Zone” along Somerville Ave.

A development over the tracks would replace that fence with a wall supporting the deck over the tracks and potentially small retail shops leading up into a hotel or apartment building.

Why not an office building? The parcel’s dimensions—it narrows from 70 feet to 50 feet traveling east along Somerville Ave.—make it most amenable to hotel or apartment use.

“The basic widths of different building programs come in general dimensions,” Love explained. “And a typical apartment building with a central corridor typically wants to be 63 to 65 feet wide. So you see that even for residential uses, for a kind of corridor-accessed multi-family residential building, it gets a little bit narrow as you head down Somerville Ave. Those are dimensions that are a little bit friendlier to hotel uses.” Love concluded, “We’re talking about residential or hotel but not office functions.”

In any case, building a deck above train tracks is very expensive. “Development costs more building on a new artificial platform than it does on terra firma, on the ground,” Love said. The proceeds from a new building would be unlikely to cover the cost of its construction, he said.

In order to cut construction costs, Utile advised the MBTA that, “You don’t need a development taller than 70 feet, because a developer wouldn’t pay the additional construction and code costs to go to high-rise.” With a shorter building—four floors above the parking level, maximum—the developer could use wood-frame construction and avoid the additional costs associated with the steel and concrete framework of a high-rise building.

Previously, the MBTA hired LeMessurier, a Cambridge engineering consulting firm, to determine exactly kinds of structures would be tractable over the tracks. LeMessurier determined that the deck would have to be about eight feet above the sidewalk in order to clear the trains safely. The next level would be for on-site parking. So the first usable floor of any building would be more than one level above the street.

In order to draw pedestrians to the building, Love has proposed what he calls “chiclets” of ground-floor retail. He imagines small shops interspersed with landscaping lining the space between the sidewalk and the wall of the parking structure.

“Our thought was that if you could slide the building as far away from Somerville Ave. as possible so that the face of the building lined up with the Somerville Ave. cut, you’d have about eight-and-a-half feet to play with behind the sidewalk. And that could be a place where we could get a thin liner of retail. And that could be a solution to getting people through elevators and stairs up into the blue stuff,” he said, referring the upper four floors of the building, blue in his Powerpoint diagram.

Those are the engineering challenges a developer would face building above the train tracks. What do community members think about such a development?

One woman, who did not want to give her name, thinks that a new development would just exacerbate what she sees as a traffic problem on Somerville Avenue. She does, however, hope that someone will improve the fence between the tracks and the sidewalk. “Someone is going to get killed there, and then they’ll fix the fence.”

Others were more positive. “We want Porter Square being used to its full capacity” commented Hong Liu. Mary Norcross, who also liked the idea of building over the train tracks, added: “What we want to do is draw people from Porter down to Wilson,” the lesser-known square east of Porter. Jeff Myers called the unused space above the commuter rail tracks “a wasted opportunity.”

This is not the first time the MBTA has considered selling air rights at Porter Square. The T put the air rights on the market in 2003 and accepted a bid for them, but the economic downturn stymied the development. Since 2008, the MBTA has been reconsidering the idea.

No developers are involved in the current project at this point; the MBTA has not put the air rights on the market. They will only do so, Dicovitsky and Love assured people, when they are sure that a development makes engineering and financial sense and would benefit both Cambridge and Somerville. “The T is interested in this being a positive for all the neighborhood,” Dicovitsky said.

Reader Comments