Three undocumented Salvadoran immigrants have shared stories of their journey from their former homeland to Somerville.

By Jeffrey Shwom

Somerville has been a Sanctuary City since 1987, and, per resolution, strives to “protect the safety, dignity, and rights of immigrants, migrants, asylum seekers, asylees, and refugees” by limiting its cooperation with the Federal government in enforcing immigration law.

Even as Somerville reaffirmed its commitment with a revised Sanctuary City Resolution three weeks after the November 2024 election, the day-to-day, year-to-year experience of its immigrants continues on. The Times was able to sit down with three Salvadoran undocumented individuals to hear their stories of why they came here, the communities they left there and built here, and their vision for a more just future.

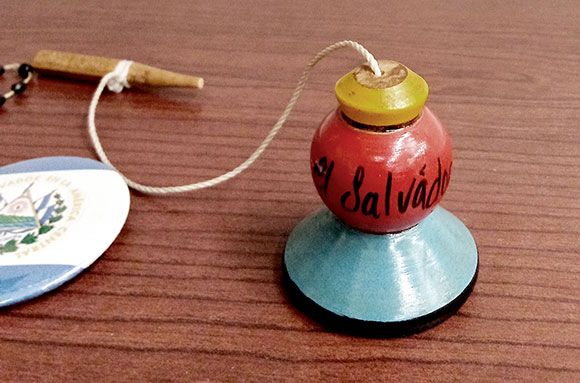

The group discussion, held in East Somerville near the East Branch Library, began with cups of coffee, pastries, and conversations about family. All three of these women come from large families, one telling us that she has 14 aunts and uncles. Things got more real quickly, as they talked about the struggle of not being able to travel back to their country to visit aging relatives, because of their undocumented status. All three have or are taking English classes. They brought things from their birthplace, like rosary beads from the desert and a capirucho, a wooden toy that consists of a bowl with a stick attached to a string.

To protect their identity, all names have been omitted and no photos taken. Conversation was translated from Spanish through a bilingual interpreter. The discussion focused on two questions: why did folks come and what were their plans on staying, in the context of their status and other national or global factors?

The first person to speak is a natural born leader, one that the interpreter earnestly asked to run for public office someday. Her goals were to come here, earn money, and to buy her own home in El Salvador. When she came from El Salvador earlier in the 2000’s, she came from a poor family and there was no opportunity for work. There too was a lot of fear. Someone could be selling vegetables on the side of the road, she told us, and folks would mug you, take everything, or charge a fee. They would chase kids in schools and hire them into gangs. She birthed her first child in the States alone, with no family at the hospital, with her husband was detained by Immigration due to work issues and the rest of her family abroad.

It is hard to be away from her “miyos,” roughly translated as community or “my people.” That being said, now that she and her kids are settled in here, it becomes harder to think of moving home, because they have created “another family” here. She discussed wanting to go back to show her children their roots, while also realizing that having children in school helped them learn about opportunities in this country.

The second person laughed at the naivety of her younger self. She came here for “a better life, a better salary.” It was only once she arrived that she truly realized the reality: her high school degree with a focus in accounting (something common there) did not mean anything here, she did not know English and she did not have papers to work. “Whatever education you had there is not valid here,” she laughed. She talked about the barriers that continue to hold her back. She has all of the Early Education and Care (EEC) credits to become a daycare teacher but she cannot get the job because she is undocumented.

According to the American Immigration Council, a Washington-DC based nonprofit that conducts “litigation, research, legislative and administrative advocacy, and communications” related to immigration issues, there is no line or clear, easy pathway for undocumented folks to gain citizenship. In their 2021 paper, Why Don’t Immigrants Apply for Citizenship, “most undocumented immigrants do not have the necessary family or employment relationships and often cannot access…refugee or asylum status,” the three limited routes to be in the States on a temporary or permanent basis.

The third participant knows how to operate a Bobcat used in construction. She did it for 15 years but could not get a license to operate. She could make $50 or more an hour if she had the license. Also, she used to work for a recycling company in Boston in 2019, where more than 40 people lost their jobs when they asked for their papers. Since then, she has worked at a restaurant in Boston and has been learning English on the job. She had a happy life in El Salvador. There was no crime and no gangs where she lived, and she could just pick fruit and mangos from her farm. However, she came from a family of nine kids with five brothers. So, she came because she wanted to study and find an opportunity. Her daughter attends medical school in the United States as she was born here.

Other than the personal stories, they talked about four overarching themes. First, folks have to take deplorable jobs in the US, like cleaning toilets and working tough construction jobs, and there is shame. For example, one person described, “if you are cleaning a house, you may get dropped off and you do not get paid. They (bosses) violate your rights. They see you like a slave with a little bit of salary. We still pay taxes even amongst this.”

Second, the folks said that the way that they were taxed or had money taken out of their pay was different than those with status. Some described extra taxes taken out but were unsure who took the taxes: their bosses or the government. The third person relayed her situation about how her husband has a social security number but she has an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN). When they file taxes together, she cannot get federal taxes back while he gets federal taxes back. Even though she is working legitimately with her name and the proper procedure, she estimates about $2,000 a year in lost wages.

Third, all of them see that El Salvador is getting better and safer, which could contribute to decisions about staying here longer. Since 2019, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele’s Territorial Control Plan has decreased crime and increased tourism, though wages have stayed low and the cost of living there has risen.

And last, folks are not just sitting around and not contributing. They are taking the opportunities to move up. If they are able to get their documents, they have a strong desire to do more and earn more, to grow wealth and opportunities for their families, here and at home.

In the end, even with the conversations of hardship and the realities of life here, there was a sense of community and belonging. Sharing these stories seemed to help three women connect. Though their experiences and circumstances differed to begin with, they shared the room equal in status and equal in their hope for a better future for themselves, their children and their families.

This article has multiple falsehoods in it that could negatively impact our immigration-statused neighbors.

Filing with an ITIN jointly with an SSN holder, you can get a federal tax refund. You are not eligible for some tax credits, like the earned income tax credit, where the SSN holder is. This could reduce or eliminate a refund, but it is not a hard truth like this article incorrectly states.

Additionally, it’s concerning to see the hard-right Bukele’s mass incarceration campaign praised here. As we strive to imagine a police-free world we cannot give a bitcoin bro like him any credibility.