*

*

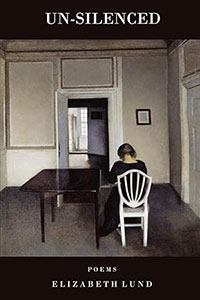

Recently, I caught up with poet Elizabeth Lund to talk about her recent collection of poetry Un-Silenced (Cervena Barva Press). It seemed fitting because this month is National Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

Poet Michael S. Glaser, Poet Laureate of Maryland 2004-2009, wrote of this book: “Poetry is one of the few art forms that enables us to approach extremely difficult and complex human experiences without having to turn to didacticism or preaching. Lund’s poems do this exquisitely as they grapple with the intense emotions of a woman trapped in an abusive relationship. Each poem is a compelling piece of a much larger puzzle – one that explores the effects of toxic masculinity and the debilitating fallacy that a woman can free her abuser from his own darkness.”

With the concision of Emily Dickinson who taught us to “tell all the truth but tell it slant -,” and a stream of consciousness narrative, Lund creates the perfect modality to convey an intense and painful journey that generations of women have experienced.

The result, Un-Silenced, is an absolutely stunning, heart-rattling read that implores us to open our hearts and minds.

Doug Holder: This book deals with domestic violence. It has been said great pain brings great writing. Was it the pain of your aunt’s murder by her husband that drove you to write this collection?

Elizabeth Lund: The short answer to that question is yes. The longer answer is that I never planned to write about my aunt’s death because I didn’t want people to think I was exploiting a family tragedy or dredging up painful memories that should fade into the past. Yet a few months after her murder, I was still so upset about what had happened and the fact that her life story had been reduced to “murder victim” in the press, that I wrote one poem. The act of writing made me feel better for a while because poetry allows us to address troubling topics and transform them in some way. I penned another poem a few months later, and another after that. Each time I wrote, I felt that I was challenging the silence that paralyzes so many victims of domestic violence and contributes to their pain.

DH: I know when my wife died, I looked to birds for her presence. We had decided that she would communicate through a bird after she died. You use animals, nature, as stunning metaphors for your aunt – and your world. Is it natural for you to pick up on these vibes, or has it been more of a long meditative process?

EL: I’m glad that birds allowed you to feel your wife’s presence. I can definitely relate to that because I have always felt “vibes” from the natural world that remind me to look beyond the surface level of life and to examine the thoughts, feelings, and unseen currents that shape and underpin what we experience.

Once I realized that I was writing a series of poems – it felt like I was compelled to write them – birds and other animals appeared effortlessly, as if they wanted me to pay attention to the symbolic messages they were delivering. Birds, of course, can rise above us, migrate, and travel places we humans cannot go. Lion cubs represent strength and power that hasn’t been realized. I didn’t think about those meanings as I wrote, but once a poem was finished, the message became clear.

As the series expanded, I started to consider how the poems were connected. One group dealt with my aunt’s death; a second group presented the voices of other women who have been impacted by domestic violence; and a third group allowed me to grapple with my feelings about what had happened and try to find some sense of redemption.

For months those groups seemed disjointed because there was no connecting thread. Then an owl unexpectedly appeared in a poem I was revising. The raptor said what the humans couldn’t, or wouldn’t, see or articulate.

As I continued to revise, owls appeared in several other poems as well, acting like heavenly guides who were trying to nudge, direct, or rouse the struggling humans.

DH: In an interview you speak of silence as being a killer? How does it kill, and what does it kill?

EL: I love what Laurie Halse Anderson once said about silence: “When people don’t express themselves, they die one piece at a time.”

That’s very true. Silence can seem like protection when you are dealing with someone who is angry or controlling. Yet over time, it erodes your confidence and your ability to speak up about situations that need to be changed.

When silence becomes a habit – a form of avoidance – it reinforces the idea that you must resign yourself to a small life, a life that’s defined or conscribed by fear. That view makes it extremely difficult to make life-changing choices, such as leaving an abusive situation, or even reclaiming your voice.

I learned this firsthand when I was engaged to someone in my early 20s. My fiancé often told me how worthless I was and how lucky I was that he loved me. As months passed, I became quieter and more passive, and my posture changed. I looked down constantly, both literally and figuratively. Deciding to leave was the most frightening thing I have ever done; people who intimidate or abuse others don’t like to lose control.

DH: I remember years ago interviewing Lois Ames, who wrote the introduction to The Bell Jar by Slyvia Plath. Plath was abused by her husband Ted Hughes, and it led to her suicide. Ames told me in the 50s and 60s it was a revolutionary act for a woman to step out of the kitchen. Things have changed, and things haven’t changed. What is your take on this?

EL: Many women experienced domestic violence in the 50s and 60s, yet despite the gains women have made in many areas since then, violence is still pervasive today. The US Department of Justice estimates that 1.3 million women (and 835,000 men) are victims of physical violence by a partner every year.

As #DomesticViolenceAwareness notes, abuse often begins with a partner putting you down, acting jealous or possessive – i.e., constantly checking up on your whereabouts and wanting to know who you’ve been with. Abusers “attack your intelligence, looks, mental health, or capabilities. They blame you for all of their violent outbursts and tell you nobody will want you if you leave.”

As the site also states, abusive behavior leads to the self-esteem of victims being “totally destroyed,” which makes it difficult to even consider escaping. When someone does leave, that’s the most dangerous time. “Women are 70 times more likely to be killed in the weeks after leaving their abusive partner that at any other time in the relationship,” according to the Domestic Violence Intervention program.

DH: Why should we read your collection?

EL: Domestic violence is so pervasive that many of us will have a friend or family member who deals with abuse at some point in their lives. My book shines a literary spotlight on that struggle and the devastating impact that abuse can have on everyone involved. To put it another way, the poems provide a series of snapshots — rather than statistics – which allows readers to understand viscerally both the warning signs of violence and the pain that victims feel.

I’ve been told by several women who escaped abusive relationships that my book beautifully captured their experience and helped them realize how strong and wise they really were. Others have told me that the poems helped them release any lingering doubts about their self-worth or the idea that they somehow deserved what happened.

Still other readers have said that they appreciate how the book moves from darkness toward light and reminds them that no one deserves to be silenced or afraid. I’m deeply touched by such comments.

Thank you, Doug, for your thoughtful comments about my poems, especially since National Domestic Violence Awareness Month is coming up in October.

Remembering Elaine

One great blue heron

punctuates the shore,

huddling in first snow.

What keeps this steel-eyed

juvenile here, weeks after

the others have flown?

Gray on gray she stands

like a wrought-iron

question mark.

What does she read

in the tinfoil sky,

its indecipherable script?

Does she stand, like me,

awaiting a sign, has she

hunkered too far down?

How do winged creatures

lose their lift, their bold

exclamation point?

One could say the sky

turns a deaf ear, that some

stories are meant to trail off.

She stands ramrod straight,

like a stubborn suicide

or a righteous sacrifice.

But I’m not ready to let

her go, as the season’s

first storm spits and swirls.

— Elizabeth Lund

Reader Comments