*

*

Reviewed by Off the Shelf Correspondent Karen Klein

My first reaction on reading this book was what an incredible group of women.

My second reaction: I wish I were one of them. I predict you will, too, when you read this amazing anthology of their poetry, prose, and plays.

The Streetfeet Women were multicultural before that became popular in the USA. In Somerville, MA’s, Winter Hill in 1980 a Black American, Mary Milner McCullough, and a White American, Elena Harap, began their literary partnership with Portraits of Sisters, a production of poems, music and dance performed by a multicultural groupof women. In 1982, they became formally known as “The Women’s Touring Company a part of Streetfeet Workshops of Mission Hill.”

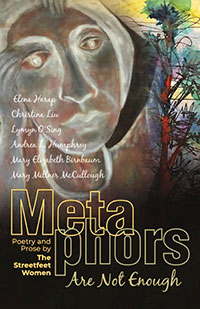

Metaphors Are Not Enough

Poetry and Prose by The Streetfeet Women

(2020)

Starting first with local performances in the Greater Boston area, tour they did: to Nairobi, Kenya for the Conference on the Decade of Women in 1985 and to Beijing, China for the Fourth UN World Conference on Women in 1995. Although some women have belonged for a while and new women, including Asian American women, have joined the group, their core has remained active in writing and performing from 1982 until at least 2020 when this anthology was published. And it’s very informative.

An impressive list of performances, readings, publications, and awards from 1981-2019 is included at the end as well as brief biographies of the current members with their pictures and a list of Former Streetfeet members, both those still living and those deceased. Individual acknowledgements by Mary Millner McCullough, Elena Harap, Lymyn O’Sing, Andrea L. Humphrey, Christina Liu, Mary Elizabeth Birnbaum gratefully show appreciation for those who have helped them and there is a general acknowledgement for poet and author Kathleen Spivak, “always a vocal cheerleader for Streetfeet” and website designer, Kim McCullough.

All the visual artists whose work is included are listed by name. The book’s title is taken from a poem, Absolution, by Christina Liu in 2019; the full stanza from which it is excerpted is The metaphors are not enough, are not beating flesh. Your other pulse, the poem moves to beautifully expressed eroticism, but what I have quoted expresses the viscerally physical nature of the writers’ engagement. They put flesh on the language, directly and unsparingly telling the necessary and essential stories about racism, sexism, how economic inequality is entangled in all our histories and our lives. As might be expected, their poems, plays, and stories focus on these issues on the lives of women, pulsing with questions and truths about female identity, self-knowledge, and mothers.

Editing and producing the book is a joint effort of members of the group who have chosen to divide the texts into five thematic sections: Freedom and Justice, Identity and Culture, Intimacy and Love, Friendship, Evolving Worlds, but several of the texts could fit easily into many of the sections as the themes overlap and interconnect. Larger political issues of Justice, Freedom, Culture are always linked to the personal lives and literary work of the contributors.

For example, Mary Elizabeth Birnbaum’s poem On What It Means to Be a Woman evokes images of the natural world and unites with them:

We humans rear up,

as if to grow treelike into the sun,

But what I , human female–

mammal–seal sister–mean by woman,

t two souls have shared my one body;

I’ve been earth with a living ocean.

In contrast, Christina Liu’s wickedly satirical poem Perfect mocks the usual stereotypical expectations of/for women: acquiesce to all men and elders. My orgasms always/ coincide with the other. I then make toast I never /snore. But the poem closes with her wish for herself: To walk solitary on city streets. To smile for no one. and ends with her puzzlement about the possibility of female freedom: What is this?

Lymin O’Sing’s prose Healing Through Ancestors connects her identity through talismans of Chinese culture: Taichi, calligraphy “Writing with a brush is a meditation….Each stroke is one breath or one movement, never repeated or painted over….In my meditation, my elders came to me, even though my crude, awkward calligraphy made them laugh. I had no idea how much I needed the power of the ancestors, their magic, and their wisdom, their evolved transformative souls.” In another of O’Sing’s pieces To Get Close to My Mother, she explores her complex relation to the “battle-worn mother of eight children” who didn’t want to be female, but was trapped by it. “Deep inside, she was a man who didn’t want the messy side of tears or to be bogged down by that sentimental romantic femininity… She was not the cuddling type because there were just too many wounds.” But her mother “always had to wear full make-up to go out to the men’s world.” Very successful in that world as a published writer, journalist, her mother presented not only a personal, but a professional challenge to her daughter as O’Sing is also a writer. She explores every possible way to describe her mother, concluding “There were just too many images” of that “ninety-eight-pound dragon lady with her Parker Pen as her sword.”

Elena Harap’s prose reminisce, Minutes of the Meeting, presents the challenge of a dual religious identity that also has a nationalism attached to it. She finds old records of meetings of her Jewish father’s family meetings, her paternal grandparents Moses and Yetta, names “that seem to have power to define” transformed from the Yiddish Moishe and Yechovid at Ellis Island where to their relief they were “liberated from a life under the threat of poverty and pogroms.” Her father married a Protestant and was not close with his natal relatives who disapproved of his marriage. When she finally met her father’s siblings, Harap felt her “tribal identity” which “while it didn’t detract from my individual sense of self, gave me a grounding which has lasted ever since.”

Mary Millner McCullough’s humorously serious DNA and Mayonnaise tweaks the problems and discoveries that DNA testing produces. One of her women friends “turned sixty and became JEWISH right in front of me, in my kitchen.” “I knew she was Jewish but none of that was part of the equation of our friendship. I’m Black, she’s Jewish. The only identity that counted was that we were women.” In her fictionalized story, her daughter gives her a DNA test kit and she uses it. When the results come back, her daughter calls her and exclaims “You’re white!”

Her two plays, Twilight Time and Smoked Oysters have their characters express hard emotional truths about racism and aging. Smoked Oysters brings in death and old age. The main character, Ulysses, refuses to believe that his wife is dead, insisting “She left me.” He refuses to get dressed to go to her funeral, but with a poignant awareness says, “I don’t like the lonely in old.” In Twilight Time, Celeste, the wealthy white woman goes to the home of her Black maid Eunice, recently deceased, for a condolence call. The dialogue between Celeste and Nora, Eunice’s daughter, reverberates with Celeste’s misunderstanding of her relationship to her maid, claiming deep friendship while never acknowledging the racial and economic power imbalance. Celeste expected that Nora would replace her dead mother as her maid, but Nora has other ambitions and is going away to get an education. When Celeste remonstrates with her, Nora lashes back: “You came to my house and you took my mother away. She was my beautiful fairy godmother but when she went to work for you, she became the tired old witch.”

Yet McCulloch is too perceptive about the complexities of human relationships to leave with a stand-off between the women as the easy answer. Nora admits that Celeste and Eunice shared something she didn’t understand: “You might even have been—friends.” Calypso, an excerpt from Andrea Humphrey’s forthcoming novel, The Curve of the Stone, is a dialogue between two teenagers, both now working in the same Woolworth’s who meet again after having been in grade school together. Nel is white, as a sales associate, has a locker for her things, while Pam is black and hangs her things in the broom closet. But Pam is a “Cleaner. I clean shit. Same as my mom for fifteen years.” Nel doesn’t understand, remembering Pam was in honors math, saying “you should be a cashier.” The continuity of racial injustice is both acknowledged and overcome by female friendship. Both girls know their boss is a sexual predator and quit their jobs. Nel acknowledges that her father made her break her grade school friendship with Pam.

These writings express hard truths. So does the work of co-founder, Elena Harap in her courageous poem about abortion ironically titled Birth Control with its sympathy for both the mother who doesn’t-want-to-be-one, aware of “the bucket of tissue on the clinic floor, remains of what they have made” and the young GYN who both consoles her and performs the procedure. I am impressed by the way so many of these writers express contradictions while containing both sides without denying either one. Each of their writings is dated; Harap’s poem A Lifetime Barely Readies You was written from 1984 to 2019. In it she directly confronts the three decades of ambition she swallowed and realizes The fiery images of old age are flashing/toward you//and you may live to shuttle outwards, approaching that iridescent green, that subtle orange.

The voice of the other co-founder, Mary Millner McCullough closes my review. She said “Your voice has value in the world. Speak.” Their voices do have value. My gratitude for their speaking, their gift to all of us.

Reader Comments