*

*

Interview by New England Poetry Club Co-President Doug Holder

In (2007) when I was running workshops for the Voices of Israel organization based in Israel, one of the workshop members was a young poet, Dara Barnat. Well, since then she has become a distinguished academic at Tel Aviv University, and has come out with a fascinating piece of scholarship. I caught up with her recently to talk about her new book Walt Whitman and the Making of Jewish American Poetry.

Doug Holder: In a sense, Whitman looked rabbinical with his long, white flowing beard, so even visually he could be construed as a Jew. Was he ever mistaken for one during his life?

Dara Barnat

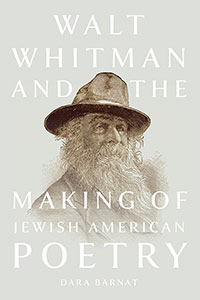

Dara Barnat: Doug, first, thank you for these thoughtful questions and your interest in Walt Whitman and the Making of Jewish American Poetry, which is set to come out with the University of Iowa Press (Iowa Whitman Series). I’ll do my best to give some thoughtful answers. Though I’ve been asked a few times whether Whitman was actually Jewish (he wasn’t), I haven’t read anything about him being mistaken for a Jewish person. However, in 1842, Whitman wrote a journalistic article called Doings at the Synagogue, about visiting a service in a synagogue on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. That article by Whitman was for me a natural starting point for discussing the numerous Jewish American poets that would come to react to, adopt, embrace, and argue with Whitman. Certainly, in many iconic photographs of Whitman, like those in later editions of Leaves of Grass, Whitman has that long grandfatherly beard. I believe it was a brilliant choice by the cover designer Ashley Muehlbauer to use a photo of Whitman that was taken in 1878 by the photographer Napoleon Sarony. This photo can be found at The Walt Whitman Archive (whitmanarchive.org) along with a myriad of other Whitman-related poems, texts, manuscripts, images, and criticism. To me, the image deeply resonates with the topic of the book and adds layers of meaning in the Jewish context by evoking a rabbinical Whitman. Here’s the link to the photo: https://whitmanarchive.org/multimedia/zzz.00067.html.

DH: Whitman fits the image of the Wandering Jew, who in legend was condemned by Jesus to wander the earth until the Second Coming. Whitman was an Adonis of wandering, and on his travels, he took in everything he saw and used it in his flowing free verse.

DB: That’s an interesting association and I agree about Whitman’s free verse form. In Whitman’s poetry, there doesn’t seem to be any person, place, or thing too small or insignificant to bring into a poem. I might not say that Whitman was “condemned” to walk eternally, like in the myth of the Wandering Jew. Often in Whitman, walking (whether in the city or in nature) is depicted as a joyful and exuberant act, like in lines from section eight of the 1891-92 version of Song of Myself, “Pleasantly and well-suited I walk, / Wither I walk I cannot define, but I know it is good, / The whole universe indicates that it is good.” This walking, witnessing, and recording in poetry what one sees is later reflected in the work of various Jewish American poets, each with different styles and ways of doing so, like Charles Reznikoff and Allen Ginsberg. The poetry of Gerald Stern has this quality, as does Muriel Rukeyser’s (though again, in distinct fashions). A commonality between all these poets is that the trope of walking is essentially democratic – a way for the poet to honor everything and everyone, and to bring those on the margins and the sidelines into the center.

DH: Matt Miller opined in a blurb for the book that you show how Jewish poets redefined Whitman. How so?

DB: I believe that Matt Miller’s remark here relates to Whitman’s legacy, and how it is shaped by the poets, writers, and critics that respond to him. In the case of this book, I specifically examine the tradition of Jewish American poets (and primarily English-language poets, with the fascinating turn to Whitman by Yiddish-language Jewish poets discussed, but largely beyond the scope of my project). I’ve long been drawn to issues of critical reception – how perceptions of Whitman as an iconic poet change radically according to literary, historical, cultural, and political shifts. I trace interpretations of Whitman in Jewish American poetry, prose, and interviews from the mid-19th century, through the 20th, to the contemporary moment. These responses by Jewish American poets have lent themselves to Whitman’s reputation as the paradigmatic American poet today (while also not a straightforward matter in terms of some of Whitman’s writings about race). I’ll add that questions about Whitman’s reception are in no way limited to the Jewish and/or American literary framework. Responses to Whitman have been analyzed by scholars of many literatures and in many languages across the world. This body of critical work has served as a vital foundation for my own research. One major reason I’ve stayed curious about this topic is due to its nuanced, ever-evolving nature.

DH: What did the wandering New York City poet Charles Reznikoff have to say about Whitman? He seemed like Ginsberg and others to be heavily influenced by Whitman’s work.

DB: Yes and yes! If Charles Reznikoff and the group known as the Jewish Objectivists are of interest, chapter one focuses on Reznikoff and this milieu of the High Modernist period. The poetic adoption of Whitman displayed in Reznikoff’s poetry is a lot subtler than in Ginsberg’s, and there are sources where Reznikoff says he doesn’t even like Whitman that much. Yet Reznikoff’s poetry is found to be pretty steeped in Whitman’s poetics, not only thematically, but formalistically. And Ginsberg later expresses appreciation not just for Whitman, but for Reznikoff, which challenges an assumption that Ginsberg was the primary Jewish American poet to turn to Whitman. Reflecting for a moment on my research process, back when I was working on this project in dissertation form, I intentionally chose to leave Ginsberg out and look at Whitman in lesser-recognized Jewish American poets. When I was developing the manuscript for this book, I realized that I had to do new research and re-situate Ginsberg vis-à-vis this wider genealogy.

DH: You are a poet. What attracted you to Whitman’s work?

DB: I would say first the music. The rhythms that resonate as prayer-like to me. Empathy. Inclusiveness. Compassion for the self and the other. Life and death. If I may, in 2016 I did an interview with Jessica Mason for the wonderful journal Poet Lore. I hope it’s okay if I link to it, since we had a delightful discussion (over email) pertaining to Whitman as an influence in a creative and poetic sense.

http://thewriterscenter.blogspot.com/2016/07/uncovering-whitman-with-dara-barnat_28.html

DH: Why should we read this book?

DB: If Walt Whitman, American poetry, Jewish American literature and poetry, outsider identity, democracy, intersections of poetry, politics, and culture, and critical reception are of any interest, I extend an open invitation to do so. I’m honored for the book to be part of the Iowa Whitman Series, together with scholarship on Whitman from a multitude of orientations, which can’t but evoke the famous quote in Song of Myself, “I contain multitudes.” There are a multitude of ways to approach Whitman, and this book is one contribution to the enduring and dynamic conversation around Whitman. And Doug, again, thank you for taking the time to pose these questions!

Reader Comments