*

*

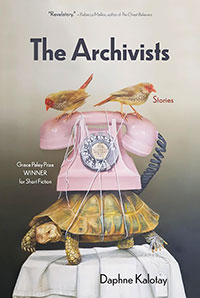

I caught up with Somerville writer Daphne Kalotay, who has a new collection of short stories, The Archivists. Published in 20+ languages, Daphne Kalotay’s books include the award-winning novels Russian Winter, Sight Reading, and Blue Hours, and two-story collections: Calamity and Other Stories, shortlisted for The Story Prize, and the Grace Paley Prize-winning The Archivists, forthcoming in April 2023. A recipient of fellowships from the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, MacDowell, and Yaddo, she lives in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Doug Holder: You are a Somerville writer and I see you have a story in your new collection that is based in Somerville. It is about the death of a woman who lived with cancer for nine years. It is, I believe it is about your late friend’s life. Setting is so important in fiction. How is Somerville a character in this story?

Daphne Kalotay: Yes, multiple stories in the book are set in Somerville, though the town is not named. In the one you refer to, Heart-Scalded, the entire story takes place at a party in one of the big old houses I particularly love here – in this case, one that hasn’t yet been fixed up and sold off. The house is inhabited by a few thirty-somethings who rent rooms from the woman’s friend, who also lives there. People at the party include former renters who have moved on – either managed to afford something on their own or taken a job in another state altogether. I think this situation is very real for many folks in Somerville, especially people in the arts, who want to live in town but can’t afford their own place and may eventually have to move away to continue to be able to support themselves (or the more typical “adult” lifestyle we are taught to aspire to). That theme – precarious financial stability in a city that’s been rapidly gentrifying – is a strong throughline in the other story, Providence, which addresses gentrification much more explicitly.

DH: I have always been fascinated with food in fiction. Proust had his little madeleine, and you have an obscure French appetizer in your short story Egg in Aspic. I remember in graduate school I did my thesis on food in the fiction of Henry Roth. At first my advisor thought my subject would be trivial, but I proved her wrong. How did you come up with the idea of this morsel as a symbol for the story?

DK: I love that you chose that subject for your thesis! I imagine it was incredibly interesting to write and for your readers. In my case, the idea for this story first came to me through the setting, which then led me to the specific dish. A foodie friend and I had gone to a tiny cramped French restaurant much like the one in the story, and I found it comical that this somewhat physically uncomfortable situation was so coveted. Then, a wonderful artist and thinker living in Somerville at the time, Arlinda Shtuni, invited me to contribute a written component to an art exhibit she was curating for the French Library called In Search of Lost Memory – there’s your Proust reference. The theme of the exhibit was how the internet might be affecting our memory, so I had a prompt, and the French tie-in and Proust reference caused me to recall the tiny French restaurant, which I’d always thought would make a great setting for a story. I felt that since the physical space was small, the story itself should be very brief, which would work well with Arlinda’s parameters. I then recalled a dish I’d eaten in France, the oeuf en gelée – or Egg in Aspic – and realized that this amazing concoction perfectly encapsulated what I wanted to say about life and death and our own ephemerality, the way it seems to preserve a tiny scene (with an egg so representative of life and birth) that is then destroyed, and that the people in the restaurant were their own little scene within their own little jellied egg, trying to preserve their moments of experience on their phones, etc. These themes – memory, archives, how we communicate our experience to one another, and what is lost – form much of the connective tissue of The Archivists.

DH: Of course, each life will eventually end – you become off the table and out of the game, and then … gone. But life goes on for the living, for the survivors. In your work you deal with absence, how it affects us, how it changes our perception – how we need it to truly feel.

DK: Yes, many of these stories concern survival and perseverance after loss. In some cases, I’m drawing on my own family’s decimation by the Holocaust and what I know of that history from the survivors in my family – what life looks like after. Each person’s way of interpreting the world and moving forward differs from another’s. But absence – whether it’s a namable loss (death, dementia) or just a sense of something missing (loneliness, lovelessness) – certainly has its own shape and effects how we interpret the world around us.

DH: If someone asked, “Why should I read this book?” What would be your reply?

DK: To take a break from life and phones and appointments and instead lose yourself in a good story – multiple stories –that will both entertain and move you. To see your familiar world from unfamiliar angles. To enter experiences and mindsets and lives not your own. To laugh and maybe even cry and be transported and nourished.

Kalotay will be reading from her new book on Wednesday, May 17, 7:00 p.m. at Porter Square Books in Cambridge and Wednesday, May 31, 7:00 p.m. at Brookline Booksmith.

Reader Comments