*

*

Review by Off the Shelf Correspondent Lee Varon

Bend in the Stair is an exquisite collection from a gifted poet who looks keenly at the world and in doing so helps us see it afresh.

In his opening poem, the poet contrasts death (his father’s ashes—”wordless gray grit”) with birth, namely his own entry into the world (“pissing, screeching, astounded”). This contrast is woven throughout the book.

In The Story So Far, the poet reminisces on his own life while disposing of his departed parents’ odds and ends. The poem ends with a touching note as he sees among his father’s things: “mother’s high school pictures/ with her love note in his sock drawer.” It is poignant moments like this which illuminate this collection.

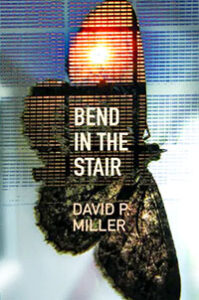

‘Bend in the Stair’

by David P. Miller

Lily Poetry Review Books, 2021.

54 p. $18.00

Intense memories of the departed are often crystallized in treasured objects. In Dinosaur, the poet recalls a small bronze pterodactyl from his grandfather’s study. Addressing the small object, the poet asks: “what allowed me to carry you away/when my grandparents departed?” It is in this poem, the title of the collection appears. As the poet drives by his grandparents’ house many years after they have departed, he writes: “Something inside must still know me.” And he continues: “The bend in the stair, ascending to the study, / knows who I was. Remembers the extinct creatures.”

These poems speak to how we hold dear the memories of our departed loved ones.

In Sunrises with My Father, the poet visits his father in a senior community in Florida. It has been twenty years since his father moved into the community when he had, “barely stepped across/ that definite senior discount line.” Spry as he was, on his daily walks, his father was happy to help other seniors by carrying their newspapers up to their doorsteps. But now, the poet, wryly referring to himself as “The younger elder,” is the only one who brings in a paper after his morning walk.

The juxtaposition between the living and the departed often figures in Miller’s writing as in one of my favorites, His Mouth. In this gripping poem, the narrator stands with his brothers by his dying father’s hospital bed. The stark contrast of a loved one who is dying in a hospital which plays the digital sound of Brahms’s lullaby whenever a baby is born in their maternity ward, is at once jarring but also strangely soothing. Even in the face of grief and imminent loss, there is the joy of new life.

As the book begins with the image of his father’s ashes, it comes full circle at the penultimate poem Add One Father to Earth in which the narrator, and many other family members, consign his father’s ashes to the earth: “Seventeen people stooped to the earth.”

Like a treasured object these poems reverberate long after reading them. I found myself wishing the poet’s father were able to read this moving tribute.

If there is anything lacking in this wonderful collection, it is that, having heard Miller read his more recent poems such as the powerful and troubling All the People Were Singing, I would have loved to have seen them here. I look forward to reading Miller’s next book!

Lee Varon is a writer and social worker. She co-edited: Spare Change News Poems: An Anthology by Homeless People and Those Touched by Homelessness and recently published the first children’s book about the opioid epidemic: My Brother is Not a Monster: A Story of Addiction and Recovery.

Reader Comments