*

*

Review by Off the Shelf Correspondent Karen Klein

In her foreword, Jane Fonda, actor, activist, and maker of the film 9 to 5, praises the women of 9 to 5 who built a nationwide movement, started a women-led union, changed the image of working women and “made it clear that women[are]workers in the own right…with rights.” She claims their story will inspire you. It does. I need only quote from the numerous examples of male bosses’ bad behavior toward their secretaries to convince you of the need for the 9 to 5 movement.

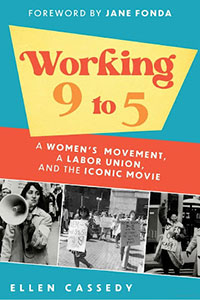

Working 9 to 5:

A Women’s Movement, A Labor Union, and the Iconic Movie

By Ellen Cassedy

Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL, 2022

Take, for example, banks in Boston in the 1970’s when this movement began. In these banks profits increased annually about 27% or more; pay for women clerical workers – and almost all the clerical workers were women – was close to minimum wage. Boston’s cost of living higher than national average; clerical women paid less than national average. Much of the forward movement of this book includes an abundance of personal stories which makes the narrative compelling and real. Diane, a bank secretary, asked for a raise; her boss suggested she see a psychiatrist. Gail worked for eleven years at the same bank and was the sole support of her 8-year-old. She applied for a job opening, but a 19-year-old male got hired instead. When she asked why, she was told “he has a new house and wife to support.”

Ellen Cassedy’s way of telling the story of the 9 to 5 movement is an example of a guidepost of second wave feminism: the personal is the political and vice versa. She tells the story of a remarkable coming together of women to make a miracle with hard work and interweaves the movement’s historical growth with her personal journey. It all begins in 1972 with a group of ten young White women who work in clerical positions at Harvard. All are educated or skills trained and have hopes for career advancement. When they meet for coffee and talk, meeting in each other’s homes, they all have the same issues. Not only are there no prospects for their advancement, but also, they are asked to do things that are not filing and typing, the job for which they were initially hired.

One woman’s boss asked her to take down a calendar in his office; a philosopher professor hired one to type out his handwritten notes which detailed all the sexual services he had ever received. All made the coffee or were sent out to get it. By the time, 1974, they wrote a 13-point Bill of Rights for Women Office Workers, it’s not surprising that the First Right was “the right to respect as women and as office workers” and the Second Right was “the right to comprehensive, written job descriptions specifying the nature of all duties expected of the employee.”

The ten women brainstormed, coined the name 9 to 5, created and reproduced with old technology a newsletter for Boston area office workers which they leafleted every morning in the office buildings and business neighborhoods of Boston. They went into coffee shops, talked with working women 9 to 5ers, visited their offices, got contact numbers, called them, invited them for coffee, joined them for lunch breaks. Gradually their numbers and their strength grew; they were getting known by management, government, and media. By 1974 they hold a public meeting and over 100 people come.

But in 1973 Ellen and her coworker best friend from college, Karen Nussbaum, realize they needed to learn how to organize efficiently and effectively. They learn of a summer school in Chicago for women organizers, partly run by Saul Alinsky-trained Heather Booth, who should be a household name for all the wonderful work she has done and continues to do to make this world a better place. Going to Chicago to learn to be an organizer brings the author into the tangled personal dilemma of how to be an organizer and a girlfriend, as she is already in a serious relationship with a man. This relationship which ends in marriage, kids, grandkids, parallels the author’s personal growth throughout the book and increased confidence in her ability to be a leader, to create a union, a movement, and to balance the life she wants.

Ellen Cassedy is honest and forthright in telling of the particular roadblocks, social, cultural that women organizing for change face. Many women are not comfortable speaking in public, or confronting strangers on the street with a leaflet, or standing up to a male boss. Comfortable speaking to other women office workers, complaining about work conditions is one thing. Confronting the bosses, the huge institutions, the cultural dicta about being ‘good girls’ quite another. But, as she says, “we see what happens when women join together and figure out how to turn their complaints into action.”

Working 9 to 5 tells that history of “complaints into action.” Cassedy begins with the origin story of the ten office workers. The first three chapters document their beginning struggles and achievements. Chapter Four ends with the triumph of the public meeting for office workers in Boston November 19, 1973, where one of the few Black women in the office workforce was among the speakers. Hundreds came; the Boston Globe headline:

Hub Office Workers Unite for Higher Pay, Overworked, Underpaid, Undervalued. They were launched.

Subsequent chapters are devoted to the work of 9 to 5 as it becomes the union 925 affiliated with SEIU, the service employees union. Most office workers hadn’t thought of themselves as labor, but realized unionizing would further their cause. Women had been in the labor unions before 925 came in, but office workers thought those union members were blue collar. They had to learn earning a living is all about work and pay.

Based on the 1912 women mill workers demand, “give us bread and roses,” 925 took the lyrics farther and adopted the slogan “Raises not Roses.” and printed it on T-shirts.

As subsequent chapters show 925 battle giant industries in finance, insurance, publications, facing down New England Telephone and Telegraph, John Hancock Insurance, Bank of Boston, readers might be confused about the exact time or year these fights for maternity leave coverage, for adequate salaries, for enforcing laws against discrimination, etc. or for going national with chapters forming all over the United States happened. But take heart because there is a most helpful and specific Time Line after the Acknowledgements. I referred to it frequently, found it grounded me in 9 to 5 to 925 to District 925’s developmental history and the historical events through which they lived.

A final word to the young women and men who will, I hope, read this book. If some of what happened, if the prejudice, the misogyny, the harassment sexual and otherwise seem excessive or unbelievable, remember this remarkable movement began in the early 1970’s, 50 some years ago. We didn’t have “me, too” then; but we had everything that that movement exposed. Diversity wasn’t a governmental or business policy yet. Very few women were in public life, elected to office or heading companies. It was a different world then, though some old problems have an unfortunate way of lingering. But in this, our current time when all good policies and changes for the better country and planet seem to be fighting an uphill battle, read this book. It will give you hope, lots of gasps of astonishment, and laughter. It’s a good read.

Karen Klein, Emerita Faculty in English, Interdisciplinary Humanities, Women’s Studies, Brandeis University.

Reader Comments