*

*

I recently caught up with the artist Julie C. Baer, an artist who revels in nature, as she paints and plants.

Doug Holder: You have exhibited in Somerville. What is your impression as an artist of the vibe of the city?

JCB: It feels like Somerville’s cultural life is burgeoning these days by thoughtful young people using a really transdisciplinary approach to social entrepreneurship. You don’t see a random restaurant or store opening, but each new space seems to intentionally respond to the local context of the community culture and contribute an interesting, and needed, new dimension, with a focus on sustainability, inclusion, and interdependence. Super exciting and uplifting.

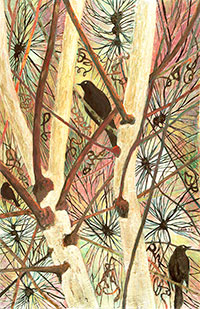

Julie C. Baer

DH: You have a series of painting titled Weird Season, created during the pandemic. In the series you explore the flowers and the fauna of the ecosystem. Although to an undiscerning eye there does not seem to be a lot going on in nature, you hear the cacophony of communication. Explain.

JCB: Weird Season was my pandemic project. In early Spring 2020, when we all were huddling indoors, fearing invisible danger from outside, I kind of forced myself to go outside every day for a walk around the neighborhood. I probably walked every street in West Somerville and North Cambridge.

I was surprised by how disorienting it felt to see green things pushing up through the cold, hard soil and buds forming on leafless limbs, such a shocking dichotomy between the dark, closed indoor space and the vibrant, open outdoor space.

Soon, spring came on in full force, bravely baring both its vulnerability and fierceness. I began visiting the Alewife Brook Reservation regularly, noticing the seasonal trajectory of plants’ life cycles: budding, blooming, fruiting, seeding, dying, renewal. I tried to photographically document my cognitive dissonance by manipulating the composition, cropping, focus, skew, color, and tonality of my casual iPhone photos, using only the built-in features in the iPhone camera – very low-tech. The resulting digital images feel quite abstract yet still organic, fresh, and plant-like.

Initially, I called the series Weird Spring, but soon it was pretty evident this nightmare was the new paradigm. I would say we are still in this Weird Season, especially in that in March 2020 my family and I had gotten super sick with what we now suspect was Covid, and am currently, in October 2022, after four vaccinations and two-plus years of masking and distancing, we are recovering from a second nasty case.

My natural creative process, at that time, was, honestly, life-altering for me. In 2007, I had stopped painting due to some mental health setbacks, after I’d been making art since I was a teenager. I decided to return to grad school to study education, particularly language and literacy. From 2007-2021, I taught reading and writing, advised, tutored, recruited, developed curricula, and directed a writing center in a variety of educational settings, including higher education, hospital workforce development programs, college transition programs, and ESOL and adult education programs in community-based organizations. By 2020, I was feeling burnt out from academics, though. And the amazing thing is that this devastating global pandemic forced me to slow down and reset, and gently brought me back to making art.

My natural creative process, at that time, was, honestly, life-altering for me. In 2007, I had stopped painting due to some mental health setbacks, after I’d been making art since I was a teenager. I decided to return to grad school to study education, particularly language and literacy. From 2007-2021, I taught reading and writing, advised, tutored, recruited, developed curricula, and directed a writing center in a variety of educational settings, including higher education, hospital workforce development programs, college transition programs, and ESOL and adult education programs in community-based organizations. By 2020, I was feeling burnt out from academics, though. And the amazing thing is that this devastating global pandemic forced me to slow down and reset, and gently brought me back to making art.

I was back in the studio, painting initially from those digital images and soon extrapolating, inventing thriving little fantasy ecosystems and the entangled, buzzing, singing cadences of life. I felt freer and more joyful than I’d ever felt making art. Your descriptor of communicative “cacophony” really felt to me like a “symphony.” I called these accumulating ecosystem paintings Confluence to acknowledge the multiple forces that brought me back to artmaking, and I exhibited this body of work in Somerville last spring at the Armory Center for the Arts Rooted cafe, my first show in forever.

DH: From what I read of you, you seem to want to address the “elitism” of art. You want art to grow everywhere, not just in the ‘gardens’ of the privileged. What have you done to empower this? What should society do?”

JCB: Sincere art can heal, teach, and include. Making art saved my life, no exaggeration. I have struggled with lifelong PTSD, depression, and hypersensitivity due to early childhood trauma. And since I “discovered” I could draw as a teenager, artmaking has served as a discipline, a calling, an identity, a space where I can belong, where I can continue to develop the “adjacent possible” in my creative process. My pain informs my empathy as a teacher, and my sensitivity enriches my depth as an artist and naturalist. And for viewers, art can inspire insight, stir hearts, light souls, stimulate freshness and hope. For example, when I worked on my memorial project Souls for ten years, large-scale portraits of children who perished in the Holocaust, I was surprised how many regular folks wanted to buy and live with these sweet faces. I strongly believe the promise of such transcendence should be a public resource, available to all viewers in everyday settings, promoted in every social context, for everyone’s intellectual, creative, and spiritual lives, not reserved for privileged, exclusionary spaces.

This is why over the years I have shown my work in public spaces: hospitals, schools, libraries, synagogues, cafes, community centers. I have participated in the DeCordova Museum’s Corporate Lending program and donated over 13 works to Boston-area nonprofits via The Art Connection. People who clean hospital rooms and office spaces, who serve in school kitchens, who work in law enforcement, etc., all deserve access. I approached education and literacy in this way too. I want my work to support and inspire viewers to care for themselves and their own biomes, to love themselves and the world.

DH: Tell us about the new series you are working on.

JCB: The natural world is our collective home, family, heritage, and future, yet humans have caused irreparable habitat, resource, and species loss and a rapidly warming climate. Native plant restoration, according to ecologist Douglas Tallamy, is “nature’s best hope” for creating self-sustaining, biodiverse ecosystems that attract native pollinators and fauna. The Wild Seed Project states “every landscape must support natural systems.” In my Rewilding series, I am painting (and planting) eastern New England native plants, and I’m just now embarking on painting the pollinators they attract, one species at a time. Gradually, this collective body will reflect biodiversity, as my urban garden develops into a biodiverse native ecosystem.

DH: I have noticed you have done book art as well. How do determine what art will go on the cover as well as the text? What is your process?

JCB: I have written and illustrated two published picture books, Love Me Later and I Only Like What I Like, and written and/or illustrated many others that I have never been able to get published. My stories are always told from the kid’s point of view. Of course, they were organically grown from the amazement of raising children. Or in the case of Lilly Looking, my (unpublished) semi-autobiographical picture book, telling my own story of trauma. In Lilly Looking, we learn through vignettes depicting Lilly’s experiences as she grows up, that her baby brother died, but no adults ever talk about it except to say, “We lost the baby.” The images are narrated by Lilly’s inner thoughts about “losing” and “finding” things. I have often seen middle-school-age girls lying around the library after school, relaxing with picture books. As adults, we understand Lilly has survivor guilt, trauma, and hypervigilance, but what teen girl would want to relax with a book that uses impersonal, clinical ideas?

There is so much learning and healing potential in stories told through pictures, with nominal text. Ideas can slip in through subtle emotional channels. But alas, the publishing industry pretty rigidly markets picture books for readers ages 2-8, so I would get rejection letters saying, “It made me cry. But who is your audience?” I ultimately abandoned the quest to publish my books, though I still am hoping to one day self-publish an e-book of Lilly Looking and my other manuscripts sitting in portfolios in storage.

I’m seeing a connection here. I always made my picture books with engaging images and ideas for both the reader and the read-to. I thought of this as nurturing the “read-aloud relationship.” As I look back, I see this thread clearly led me to return to school to study education, language, and literacy.

DH: Why should we view your work?

JCB: I can’t really answer why folks “should” view my artwork, but just that it makes me happy to share my work, especially if it can provide understanding or healing.

DH: Where and when are you exhibiting again?

JCB: Well, I currently have pieces in a bunch of far-flung juried group shows including in the Fay Chandler Emerging Art Exhibition at the Boston City Hall Gallery and at the Louisiana State University Vet School in their Annual International Exhibition on Animals in Art. Next year, in 2023:

February 2023 group show

Connections: New Members’ Exhibition

February 4 to February 25

Atlantic Works Gallery

80 Border Street, East Boston MA

August 2023 solo exhibition

Rewilding

Firehouse Center for the Arts

1 Market Square, Newburyport, MA 01950

Discussing 2023 exhibition

The Art House Somerville

862 Broadway, Somerville, MA 02144

Reader Comments