*

*

Reviewed by off the shelf correspondent David P. Miller

The title of Mary Buchinger’s chapbook is not Clouds. Rather, it’s “clouds” in the International Phonetic Alphabet. What’s the difference, you ask? Isn’t the word as it appears the same as the word pronounced? Only if we assume that what we see is the same as what we picture to ourselves. What does an upper-case block letter “a’” have in common with its lower-case script cousin? Apart from the fact that they may represent the same speech sound, not much that meets the eye. (Not to mention what a Fraktur letter would present.)

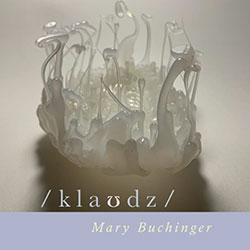

/ k l a ʊ d z /By Mary Buchinger

Lily Poetry Review Books, 2021

25 pages –

$12ISBN 978-1-7375043-7-5

Clouds have always fascinated, soothed, or terrified us. Cooled water vapor, condensed on nuclei of dust, pollen, or smoke, ephemeral entities. A web search for “cloud metaphors” retrieves what you might expect: pillows, sheep, marshmallows, the place online where you store passwords. See that profile in the sky? It looks just like the Old Man of the Mountain. But the Old Man finally crumbled, and look, that profile in the air is dissolving. It’s morphing into a sail, maybe a kite.

/ k l a ʊ d z / represents these sky phenomena with twenty different, unexpected collective nouns: a “mewl” of clouds, for example, an “unravel” or a “ligament” of clouds. Those poem titles are, exactly:

/ myul / as in “a mewl of clouds”

/ ʌnˈræv əl / as in “an unravel of clouds”

/ ˈlɪg ə mənt / as in “a ligament of clouds”

We readers get a quick assist this way with the (dis-)connection between sound and designation. But we’re also tossed right into each poem’s puzzle: what is a ligament of clouds? How is an always-shifting group of water molecules a ˌtær ənˈtɛl ə, even for a moment? (Tarantella.)

These poems are visual. Each uses the resources of the page – white space, margins, lineation – uniquely. I’m not sure these are concrete poems overall, though a few are shape poems. I haven’t seen a pocket-shaped cloud in the sky, but there’s “a pocket of clouds” on that page (ˈpɒk ɪt). It would be a wonder to see “a hive of clouds” (haɪv) from my front porch, as it’s presented here.

Buchinger’s klaʊdz aren’t composed of water vapor, of course, but text. The poems are meditations on cloud-likenesses associated with their collective nouns. The “flagellation” of clouds thrashes its tight connections:

flung; Fahrenheit;

cloistered; caught;

muddled immolation;

dry scarlet indraw;

de-berried vines;

ponderous drape;

wracked; varicose; [ … ]

The “tarantella” twists through the center of the page, beginning with “midnight & carmine; / click & grind; / Dionysius & pals / (no pall); / piped hysteria; / spidery; unpopped / herky-jerky- / stomp-stomp;” Notice the semicolons: they pervade every poem. There are commas, ampersands, parentheses, and slashes, but the semicolon – that often-derided punctuation mark between comma and full stop (of which there are none here) – dominates. Its syntactic half-linkage, which almost but not quite joins clauses, is the image of forces that give shape to clouds even as they already give way. (Let’s drop the blanket prohibitions of language resources: yes to semicolons, yes to adverbs, yes to your love-to-hate.)

Once into the progress through / k l a ʊ d z /, look back and recall that the opening poem isn’t a cloud. Titled “derivation / ˌder·əˈveɪ·ʃən /:” it suggests the ground, both earthly and inspired, from which condensed water vapor and images arise alike:

a daily ration; whence cometh;

watershed; meadow & muck;

begotten not made; [ … ]

Its final line summons the about-to-be-spoken, nearly-created: “whereas; Genesis; & etc.” It’s hard to imagine a more economical introduction to everything that follows: grimalkin, swift, braid, lantern, trans …

Reader Comments