*

*

I caught up with Somerville artist Jen Fries to discuss her evocative art.

Doug Holder: How has Somerville been for you as an artist?

Jen Fries: It’s been pretty fabulous. I’ve found Somerville quite welcoming and supportive to me as an artist – especially emotionally supportive.

I started my career in my hometown, New York City, and I also worked in Vermont for a while before coming to Somerville about twenty years ago. Both those places are amazing for the arts, of course – full of history and inspiration – but Somerville feels the most open and receptive to new, diverse voices. It’s not about who you know or whether you fit in with certain styles.

At the most basic level, Somerville is the first place I’ve lived where, when I say I’m an artist, people don’t respond with, “But what’s your real job?”

Plus, there’s an energy here – a natural energy. I don’t know how to describe it. I find the place itself inspiring. Something in the sky, the light, the weather speaks to me.

I do worry about the future. The housing crisis and the overall economy are poised to price artists out of this area, like many others. I hope that doesn’t happen. I love living here. My work thrives here.

DH: Did you formally study art?

I’m mostly self-taught.

JF: I originally studied commercial arts – advertising, illustration, and graphic design – which is definitely not the path I ended up following. I’m lucky that my early training gave me good enough insight into the business side of that field to realize I was just not cut out for it. I did learn a lot about life and professionalism, which has been invaluable.

You can still see the design training in my art, in my compositions and the messaging embedded in my imagery. At least, I see it.

In terms of the media and craft I’ve developed over the years since, it’s been all self-study and experimentation.

DH: You write that you like to bring chaos to order in your work. Have you ever tried it the other way around?

JF: This question is a bit of a challenge for me. At first, I thought, no, no, surely I bring order to chaos. Then I realized I think I do both.

My process is chaotic. The finished works are orderly. But when you get into them, start to analyze and figure them out, the order turns chaotic again.

It goes back to my early interest in advertising, which delivers messaging via imagery, either overtly or subliminally. In commercial work, you want to narrow and focus the messaging. I do the opposite. My work is crammed with layers of messaging, basically anything that comes up in the process. The works can be about many things at once, and explaining them can be like taking a walk through a maze garden.

I’d say order and chaos co-exist in my art, and it can get kind of kaleidoscopic if you think about it too much.

DH: You have written that water is your favorite medium to draw inspiration from. Why? Do you need to be near a body of water to be inspired, or does this derive from your imagination?

DH: You have written that water is your favorite medium to draw inspiration from. Why? Do you need to be near a body of water to be inspired, or does this derive from your imagination?

JF: Water is one of my favorites, and there’s a practical as well as inspirational aspect.

Practically, I use media that are portable, environmentally friendly, and as non-toxic and fume-free as possible, so I can work anywhere, especially in my home. So that means water-based pigments, inks, paper, found objects. I even make my own pastes, glues, and additives from non-toxic ingredients.

Inspirationally, randomness feeds my creativity. I get most of my ideas from accidental juxtapositions of things, events, words, memories, that come together on my walks around town, or from reading, watching the news, dreaming, etc.

I extend randomness into my media and methods, such as letting the water move the pigment for me. It makes me more a partner to the medium than the master of it.

There’s an element of abstraction to it, but I don’t have the brain of an abstract artist, so I always end up finding a picture and a story in whatever I end up with.

DH: Can you give us some idea of your process?

JF: My process involves a lot of thinking, staring out windows, and taking long walks – letting ideas percolate through my brain.

Then it involves a lot of commitment anxiety when faced with the blank canvas or paper.

Beyond those features, the process varies depending on what I’m making.

Collage and assemblage are more precise and technical. It’s slower, meditative work.

Painting, printing, and drawing are faster, more improvisational and experimental.

Some of my works are planned with a predetermined subject. An example would be an assemblage called “Judgment,” which is a comment on climate change. It was inspired by a news article about melting glaciers in the Alps revealing the remains of the lost dead of World War I. Randomness in the selection of materials was edited and composed to illustrate the message I wanted to deliver with that one.

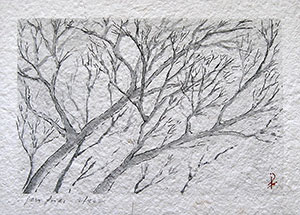

Other works are practice, in the sense of regular creative exercise, having no predetermined subject or message. An example would be my recent abstract landscapes in watercolor and ink, in which I let the subject emerge from random effects.

I do everything by hand. I have no digital skills to speak of.

I have a process as a writer, too. It’s weirdly complicated and somewhat ritualistic, with designated methods for all the stages of planning, drafting, editing, etc.

All my processes are designed to push me past my chronic perfectionism so I can actually finish things.

DH: You are also a poet. Do you find poetry and painting closely aligned?

JF: I don’t dare to call myself a poet. I try. I make no claims of success or quality.

Words and pictures have always been my twin loves, and for me, they are closely aligned. I like to tell stories with pictures and paint pictures with words. It’s all about those long walks through the maze garden.

Like the abstract landscapes, the poetry and fifty-word stories are part of my creative practice, though they are a lot more controlled in execution.

With poetry, I’m trying to learn from the haiku-inspired works of Ezra Pound and Allen Ginsberg, following the traditional principle of capturing a moment, while adjusting the form to better suit written English. I’m trying to express a lot in very few words, just as I try to capture whole landscapes in a few brush strokes.

My fifty-word stories are based on an old surrealist game, in which a full story is told in exactly fifty words. I like to add challenge by randomly pre-selecting five words which must be used in the story somehow.

I actually write more long-form prose, but only my closest friends have gotten to read it. I hope that will change soon.

For more information go to: https://jenfriesarts.com/about/

Reader Comments