*

*

Review by Off The Shelf Correspondent Ruth Hoberman

There’s a deceptive simplicity to Karen Klein’s poems. They ease into your mind, these imagistic depictions of experience (walking a bridge, listening to music, looking at art, raking the yard), and only gradually do you realize how strange and transformative they are. The book’s first poem, Journal 2017: Bilbao, sets the tone:

to walk on Santiago Calatrava’s bridge

Tis to walk on a wish

to be free of rectangles

is to honor the architect’s desire

to be a curve

suspended in space

Klein’s poems, like Calatrava’s bridge, insist on the bodily component of experience. In that opening stanza there is no “I” to contemplate these sense impressions, no punctuation to contain them: only the bridge and the feel of being a “curve/suspended in space,” which is also “a wish.” Not until stanza two does a speaker surface: she remembers an analogous swinging, stretching “my legs way out/to pump/the excitement of reaching.”

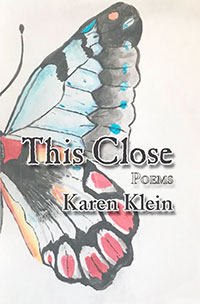

This Close

By Karen Klein

Ibbetson Street Press

2022.

77pp. $16.00

http://www.ibbetsonpress.com

The “excitement of reaching” runs throughout This Close, Klein’s first collection of poems. Giving voice to how life feels in sensory terms, the book has five sections, each titled by a line from a poem within in it. This first section, “the curvature of a line,” suggests the way a line of poetry can bend and stretch to follow a line in space, as the body’s own curves respond to what it sees.

The following two sections – “skin/has its own/vocabulary” and “use words to find my tribe” – give voice to experiences that tend not to find their way into poems. “We float in a lake of awkward,” the speaker says of an early sexual encounter. In Black Iris, a young woman sees in Georgia O’Keefe’s painting “the names/forbidden and unspoken/to the child I was”—words like cunt, labial, clitoral.

Other poems evoke the feel of dancing, skating, the pleasure of finally satisfying “our octopus arms” after the hygienic distance imposed by the pandemic. And in Alphabet Soup, letters become old lovers’ initials, as the speaker, struck by the “wild cunt-brain connection,” drifts toward sleep on the “memory soup/of good sex.”

The “wild cunt-brain connection”: the phrase feels revolutionary – even now, almost a hundred years after the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and more than fifty since Muriel Rukeyser asked “what would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?/The world would split open.” A related phrase, “choreography of the mouth,” in Indigo, links language to dance. Trace words to their origins in mouths, and they feel more sensual, more grounded in the physical world. Marking Time also explores this choreography, pointing out that “Words for wanting/contain ‘L’:/lonely/garrulous/old”:

To make the sound

your tongue touches

the top of your palate

leaving a little space beneath

for moisture

to pool

of water

in hollow places

after rain.

Structurally, This Close moves from a sense of discovery – of voice and community – into considerations of aging and mortality (the fourth section is entitled “They won’t come back next year”), then concludes in “road to nowhere/and everywhere” with a sense of meditative indeterminacy.

There’s a wry humor – incontinence as “gut knowledge/the meaning/of old” – but also a sense of foreboding and loss. In Wild Swans at Waquoit, global warming and anti-Semitic violence interrupt the speaker’s contemplation of wild swans, who become fewer and “no longer in repose”: “Their necks/elongated periscopes/strain to see what’s coming.” Finally the Yeatsian wild swans are displaced by a hint of his “Second Coming”: at the poem’s end the swans are replaced by “a massive/funnel of tree swallows that widens/into a ceaselessly moving circle/and disappears.”

But if we’re “this close” to chaos and loss, we’re also “this close” to nature and its surprises. The “swamp plants” in “Planted” “won’t come up next year,” but in October Rose, the speaker tells the flower: “ah, your color still eyeshocks us breathless”:

its pointed tip thrust directly up

defiant middle finger message

whenever anything’s over

it’s never really ever

over

“Eyeshocks”: the wonderful verb reminds me of Ginsberg’s “eyeball kicks,” linked by commentators (Michael Dylan Welch, Alex Danchev) to both haiku and the impact of Cézanne’s color juxtapositions on the eye. Klein writes in her acknowledgments that haikus have been crucial to her development as a poet. Certainly, the precision of her images, the way juxtaposed images are left to speak for themselves, the scarcity of punctuation, the way extra space sometimes separates words within a single line, forcing a contemplative pause – all feel haiku-like. Also evident is Klein’s experience as dancer, visual artist, and (until her retirement) English professor. These poems are steeped in movement and in cultural history (Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Beethoven, and Kollwitz as well as Calatrava, Brancusi, O’Keefe, Yeats, and Thomas are among those invoked).

Most haiku-like of all is the book’s final section, “road to nowhere/and everywhere,” with its embrace of contraries – movement and return; winter and spring; death and rebirth. When We Could Still Go Home describes “barren/snow-dotted farmers’ fields/leaching out the/loneliness/so deep you can’t bear it” but at home maybe a “fire/on the hearth”:

going home

the rusted metal

of old bridges

What is it about those final lines I find so poignant? Maybe it’s the tenuousness of those “old bridges” – enhanced by the space around the short lines – bridges that connect us even as they draw attention to the void below, to the gap between here and there – their rust a reminder of our own precarity, “this close” to arriving and “this close” to a fall.

The book’s final poem, the green fuse, is similarly attentive to precarity. Dylan Thomas’s “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower” depicts an abstract energy driving birth and death; Klein’s “green fuse” refers to actual hosta shoots – perky but vulnerable as the speaker starts to rake the dead leaves matting them down. Recognizing their fragility, she uses her hand instead:

…my forearm the rake’s handle

my fingers its tines carefully scoop dead leaves

inadvertently brush hosta spears

startled by their powerful thrust

the mutual shock of something live.

In Klein’s poems, the body isn’t just something we live in and lose (“at my sheet goes the same crooked worm,” Thomas’s poem concludes) but a means of engagement, full of nerve endings and expressiveness. That “mutual shock” suggests an uncanny encounter with otherness that pulls us out of our minds, into the physicality we share with the natural world.

Reader Comments