*

*

Review by Off the Shelf correspondent Denise Provost

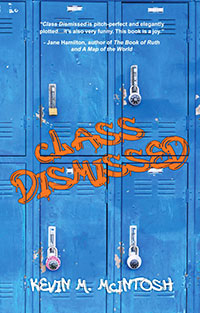

I’ve just finished one of the most intelligent, funny, and beautifully written novels I’ve read in a long time. It leaves another novel I’ve recently read – a former Booker Prize winner, which shall go unnamed – in the dust. On the chance that this novel may not receive the same attention as some of the trendier material out there, I’ll tell you why Class Dismissed is worth seeking out.

Class Dismissed

By Kevin M. McIntosh

Regal House Publishing

2021

218 pages, $16.95

Class Dismissed is a tale as unpretentious as its protagonist, Patrick Lynch, who pursues a vocation as an English teacher in under-resourced public school. “Marcus Garvey High School” in New York City serves mostly black, Latinx, and immigrant students, and Lynch learns soon enough that teaching these students is a low-status occupation. Most women Lynch’s age, on the prowl for investment bankers or attorneys as potential partners, keep their distance.

Yet Lynch pushes on, determined to connect with and educate his students. He finds his opportunities to do so by striving to understand of them and their world, which he absorbs with such clear-eyed perception that observant readers, too, may begin to parse and diagram social situations in a similar way. For instance, Lynch has the discernment to know that when his student, Abdul, “chairman of the too-cool-for-school crew,” finally turns in his late homework, he could do so “without damaging his rep, for the act of handing in an assignment was understood by his cronies as the highest form of satire.”

McIntosh’s book, for all its wit, is not satire, but is undeniably a novel of manners; specifically of the subgenre New York City fin-de- 20th century novel of manners. Like Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, it skewers that city’s self-regard, political posing, and virtue-signaling. But unlike Wolf, who seems to hate all his characters (except the beleaguered judge in the final courtroom scenes,) McIntosh displays a generous spirit towards his characters, making his book as humane as it is laceratingly funny.

Class Dismissed is also a coming-of-age novel, chronicling Patrick Lynch’s growing up as a school superintendent’s son in a small Minnesota town. We meet his family, his brilliant and disreputable best friend, his first crush. We see for ourselves Lynch’s pattern of conformities and rebellions in his early years.

In his New York City days, page by page, Lynch aptly pegs his students, colleagues, school administrators, the few parents who cross his path, and members of his various social circles. Through Lynch’s unsparing eye – and usually through the grace of McIntosh’s devastating humor – we see what’s wrong with the System in which teacher Lynch is undertaking to administer the sacrament of education.

Grading an exam after school hours, reads that of “Carmelita Fuentes…. The voice of this girl was so vivid, he could see her….[She] dismissed the Emancipation Proclamation with a finger snap and head roll. Everybody say Lincoln free all the slaves. But NO! he only free slaves in the South. And that’s the onnest truth if you want to know. Even tho he’s Lincoln he’s still a politishun. Just like them all…

“Patrick checked the rubric. Level 5: Does the writer display a thorough of the role of tone and audience in persuasive writing? No. Level 4: Does the writer demonstrate command of paragraph and sentence structure, the use of evidence in supporting a single clear thesis? No, no. Level 3: Does the writer have fundamental control of grammar, spelling, and punctuation? No, no, and no…

“He slapped Abe Lincoln down on the stack of unevaluated tests. Why did they always ask the wrong questions? Why did the rubric capture none of this girl’s aptitude or enthusiasm? Why not:

Does the writer display passion for the subject? Yes.

Does the writer appreciate the connection between history and her life? Yes.

Does the writer show evidence of having paid attention in a history class of thirty-five students, taught by an apathetic man with a degree in Phys Ed, seated next to a big girl with a sharp nail file who promised to mess her up after school? Yes.”

Standardized testing in a nutshell, stamped with the indelible voice of a girl almost no one will ever care much about – rather brilliant. Similarly, a teacher later stuck in administrative limbo with Lynch sees him carrying a volume of Proust, and asks him, “Is that the Moncrieff translation or the Enright revision?” The question, and Lynch’s reply, speak volumes. So does Lynch’s assessment, also while under suspension from his classroom, of the mission of those “agents of the Department of Education whose full-time job it was to find enough dirt on [him] to deny him the opportunity to explain to Julio what an infinitive was…”

McIntosh’s Lynch is also a cultural anthropologist of the various flavors of religion typically lumped together as “Christianity.” Lynch attends a funeral in an Evangelical Lutheran church, where the “organist ponded the opening chords to “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.” Decidedly not a hymn on St. Immaculata’s playlist, but plenty familiar to Patrick…

“And then the Lutherans began to sing. Nothing like this had been heard in the history of St. Immaculata’s, perhaps not of the entire Holy Roman Apostolic Church. The somber, aged assembly broke into the lushest four-part harmony. On-pitch, God-fearing four-part harmony.”

Lynch also wrangles with the social and theological puzzles underlying these religious differentiations: ”[f]eeling guilty and pleading guilty were very different. One Catholic, the other criminal.” He asks himself such questions as “[C]ould there be confession without actual sin?”

As its title suggests, the whole of this story of repeated failure, growth, and redemption is laced through with a finely tuned appreciation of the many – and typically dismissed – stratifications of class in America. These observations are displayed in the streetwise wisdom of Lynch’s students. These include the professors’ son, who wears his white boy’s hair in deadlocks, and plays rap, to the hierarchy of teachers and administrators, in the school, and the city’s education bureaucracy.

Lynch’s social spectrum takes in ethnic enclaves, as well as the remote world of the upper middle classes in their distant suburbs. These are mainly represented, in his world, by Patrick’s girlfriend and her family in Connecticut. He sees them – with their immersion in privilege – as “a people who viewed problems in practical terms, as soluble.”

I’ve carefully avoided revealing spoilers about the actual plot of this well-crafted story. That’s for you to find out. Read this book.

Reader Comments