*

*

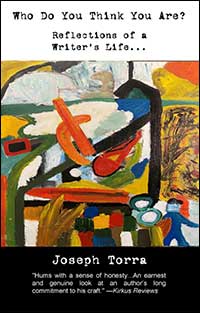

As I sat on my porch with my cat Ketz, and a strong cup of coffee – I thought about Somerville writer Joseph Torra’s new memoir, Who Do You Think You Are? Reflections of a Writer’s Life…

One of the many things that struck me about this evocative memoir is the writer’s relationship with his wife Molly. I know it is a cliché about the love of a good woman, but often clichés are based somewhat on truth. As I struggle with my own wife’s battle with cancer, I can certainly relate to what Torra brings out here. Without Molly, Torra might not have had the strength to carry on; he would not would be exposed to the breadth of the arts; he might have remained stuck in the provincial milieu of Italian working-class Medford. He may never of realized his dream of being a poet, writer, educator, publisher and editor.

Yet Torra is all these things and more. He is the author of such novels as Call Me Waiter and Gas Station, to name just a couple. He founded the well-regarded literary journal Lift Magazine, and he teaches Creative Writing at U/Mass Boston.

Torra, although he is an adjunct professor of creative writing (where he got his advanced degree from) is not enamored with the academy. He realizes its worth, but on the other hand sees its major flaws. Torra read the literary cannon – but realized that the universities are not as open to the non-mainstream voices that he was so influenced by. He has dealt with the tenure-track professorial pomposity, and the narrow strictures of a curriculum that stifled him as a youth.

William Carlos Williams, a poet who had a great deal of influence on him, searched for the “American Voice,” not the ‘English” one. And Torra’s voice is truly authentic – an amalgam of the poets, artists, writers, Medford characters, old Italian men gesturing at each other in a corner coffee-shop, not to mention all the stumble-bums we all encounter in this life. He sees life straight, with no chaser.

Influenced by Kerouac and Beat generation writers, Torra has always experimented with form. His sentences can be like a short jazz riff, or long and breathless without punctuation. His fiction writing can be likened to an abstract painting, breaking out of the confines of traditional representational imagery. There is an immediacy to his prose and poetry.

Torra is unafraid to bleed in this memoir. He tells us of his struggle with his manic depression, the vagaries of addiction, and the nagging haunt of self-doubt. But Torra is a survivor and he got by with the help of his community and the centering of his family. If he did not have domesticity in his life, and was the stereotypical footloose artist – well … he might not be here to have written this book.

Like any writer worth his salt, he has read voraciously and gained solace and insight from Taoist philosophers and poets, Mark Twain, Gary Snyder and a host of others. He counts as his longtime mentors like Gloucester poets Gerrit Lansing, Vincent Ferrini, as well as Boston literary maestro Bill Corbett. He took what he could from these men, and recognized that some of them were deeply flawed, but brilliant in their own ways. He could separate the artist from the man or woman.

Torra is not one dimensional. He is primarily a writer, but he has engaged in cross-fertilization in the arts from painting, being part of Boston’s vibrant punk rock scene, to the art of mushroom hunting. All of these things inform his body of work.

At 65, the writer looks back, meditating on his porch, at the struggle, joys, and the beauty of his life. He tells friends that “he is ready to die.” Which I can only interpret as man who is finally comfortable in his own skin, and can truly say, “It is what it is.”

Reader Comments