*

*

Review by David P. Miller

The Japanese term renga indicates a series of linked poems. Each poem consists of five lines in two “stanzas” with specific syllabic counts, the first with three lines of 5-7-5 syllables, the second with two lines of 7-7 syllables. This, at least, is how the form manifests in standard English-language practice: the relevant concept in Japanese practice is mora or “sound units” rather than syllables. If 5-7-5 seems familiar, it is: the first renga stanza, called hokku, evolved into what we know as haiku. Typically, renga are written collaboratively, and can be quite lengthy. The linkages between poems may be based on different attributes, such as (free-)association, comparison, or contrast. (There are interesting comparisons with more recent forms such as the surrealist “exquisite corpse.” On a global, multimedia scale, have a look at the collaborative Telephone Project: https://phonebook.gallery/.)

The Great Empty: A Renga in Time of Corona

By Gary Duehr

Grisaille Press [2020]

$9.95

https://www.garyduehr.com/poetry

The Great Empty is not a group product. Nevertheless, Duehr makes use of different forms of linkage between poems, suggesting associative flows discovered in the process of writing. Individual words and phrases may be transmuted. A key image in the last line of poem 2 mutates in the second line of poem 3:

This face mask, smudged, torn blossom. (2)

On a U.S. map,

The pale pink smudges swell up, (3)

Stark contrasts may mark the space between poems. Poem 22 ends with an image of the early community applause for first responders: “Block by block, Brooklyn’s neighbors / Clap their hands: a pond’s ripples.” Compare this with the first stanza of 23: “Isolate, apart / A tribe of total strangers, / We roam dusty streets.” Images themselves may transform, as between poems 24 and 25. 24 ends with an image of late afternoon quiet, from the cessation of subtle sound: “Somewhere outside a dog yelps. / The house ticks, hums, falls silent.” This is followed by an image of nighttime quiet disrupted by sound similar to, but different from, ticking: “Two a.m. Hard rain / Nails the walls down. Still awake, / You miss everything.”

Particularly complex associations link poems 34 and 35. Here is 34:

These tiny moments:

Look how bright the house-fronts are!

Night slides into day.

From the next room, the tapping

Of computer keys: light rain.

Poem 35 begins with a line repeated verbatim from 34. It sets into motion connections between rain/river, present/past, and house fronts/skyscrapers:

Night slides into day.

The house a watery dream.

A lifetime ago,

The river in Chicago

Lit up by sunny towers.

The Great Empty is, of course, more than a compendium of linkage techniques. Duehr expresses the combined shock and melancholy of the early COVID-19 period, when we learned that the disease was going to mean much more than a cruise-ship infestation. Poem 5 imagines the sudden disappearance of normal crowds from city streets as an optical illusion: “As in a 19th-century / Tintype, only transient ghosts.” From 9: “Here’s The Great Empty: / Terminals, hotel lobbies, / Train stations, plazas.” The crises of emergency hospitalizations and surges in mass deaths manifest as surreal images of the mundane: “Beds flank a parking garage. / In a field, white tents billow” (11). Our lives’ in-person events, abruptly cancelled, resulted in blanks evoking hospitals and cemeteries: “Calendar squares lie empty: / Pillows, graves” (16). The sense of being unmoored expands to include time itself: “The day / Begins its long trip – // Alone, without any bags” (29).

At the same time, the voice does not settle for despair. The poet repeatedly re-centers his perception. For example, while poem 6 begins, “We are ghosts, transients,” it concludes, “In his drive, a dad unloads / 12-packs from his Range Rover.” “Forsythias spark” in 10, there’s “a din of starlings” in 20. To focus on such phenomena is not to bypass the catastrophe. Rather, it’s to keep one’s fears and cautions situated in what has in fact not changed, what is also still real. It is not a matter of sentimentality but of psychological survival. Poem 32 melds The Great Empty’s most affirmative statement with an observation that’s acute as it is uneasy:

What can be read there?

Einstein: live as if all things

Are miraculous.

Two branches, high up, rubbed raw:

A violin’s plaintive cry.

We’ve seen that poem 35 moves to the memory a past life in Chicago. This revery continues through poem 37 and then pivots, as if a reminiscent daydream wakes into contemplation of early morning and its qualities: “The world falls open— / Breathing, quiet—the glossy / Red mouths of tulips” (39). With the 40th poem, the renga concludes, not in an easily-grasped redemption, but with space for each moment and sensation:

Between breaths, a pause.

A quiet slice of Thisness.

She’s asleep upstairs.

Your day has not yet opened.

Let each thought stretch out, release.

COVID-19 has confronted us with challenges that are, in their totality, beyond individual comprehension. Poets have provided all manner of responses, contributing perspectives that, combined, help us to understand the depth and extent of the crisis. See, for example, Voices Amidst the Virus, published by the Lily Poetry Review Press (disclosure: that anthology includes a poem of my own). The distinctions of Gary Duehr’s The Great Empty are its formal elegance and its meditative quality. While not denying the pain and alienation of this time, it allows us to step back and reset. It turns out that emptiness means room for panic to subside, as well as the vanishing of vehicles and crowds.

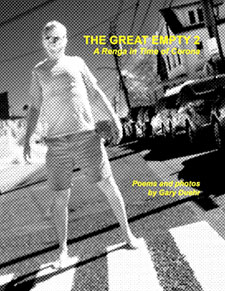

(Duehr has also published a sequel, The Great Empty 2, including “infrared, black and white photos taken in the spring and summer of the pandemic by the author, which reflect the apocalyptic, science fiction-like nature of the times.”)

Reader Comments