*

*

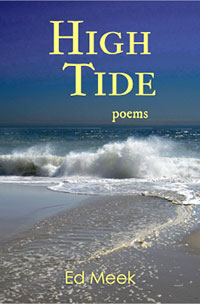

Review by Off the Shelf correspondent Dennis Daly

Holding court in his realm by the sea, Ed Meek mines the details from every corner of his kingdom for poetic nuggets that teach and transform. The raw materials include mushrooms and ethnic sensibilities, a mythological crossing guard, family memories, meatballs pertaining to human nature, and barbarian children. Meek is a veritable Everyman (in the medieval, morality play sense). His upwardly mobile progress, as he negotiates around or through annoying obstacles, is toward goodness and evolution’s steady continuity.

High Tide

By Ed Meek

Aubade Publishing

Aubadepublishing.com Ashburn,VA ISBN: 978-1-951547-99-8 80 Pages

Nor does Meek avoid intellectual confrontation. He seems to welcome it. In Meek’s world, understanding must precede judgment. But judge he certainly does. Even time bends to his moral percipience as he retrospectively determines when and where childhood happiness reaches its pinnacle.

Meek’s poem Hunting Mushrooms with Mina delights with a tour de force of description and mystery. Mina is Sioux and knows what she is doing. The poet’s persona is along for the ride. As the two seekers uncover and collect their savory dinner of morels, they seem to exchange wordless tension back and forth with a bit of playfulness. The poet’s keen senses and black humor flirt with fantasies of danger and historical fact. Here is the descriptive heart of the poem,

… She lifted leaves

and poked through thatch

to find them crouching in damp quarters,

secreted in moss and duff. They were

long-dead shrunken dwarfs

buried in their hats, their bodies

a stump beneath their shaggy, fetid heads.

They’d wept for years and moist riverbeds

Coursed down their spongy faces.

“What about these?” I asked

Pointing to a yellow disk, speckled with white freckles.

“Death cap,” she said. “I can poison you with that.”

Her long black hair reflected light and my eye

caught the tip of the blade

she kept on her hip.

Meek has a knack for hiding horror in the comfort of everyday images. In his piece entitled The Crossing Guard, the poet unveils the mythological Charon, known for his transportation of the newly dead across the River Styx, in his training role as Crossing Guard guiding children across a neighborhood street. Here is the lead-in stanza to the metamorphosis,

With hands as old as vines twisted by time

he holds the divine red lollypop—

its simple command in four black letters.

When he raises his arm, bikes cars, and trucks

like well-trained soldiers grind to a halt

as he ferries the children across the dangerous divide.

High Tide, the title poem of Meek’s collection, portrays his younger self set in an idyllic family composition. His father doubles as Elvis Presley. His mother looks the part of majorette marching down a football field. It’s perfect! Well, not exactly. Meek uses omniscience and irony to convey a prelude to the coming change of fortune. Snapshots of life are momentary and often deceiving, that is, until connected with context. The word play is quite clever. Consider the heart of the poem,

My father held me up

in the water and my mother

waved from her beach blanket

on the sand. This was before

the brothers and sisters, those

uninvited guests, crashed

the party, back when my mother

was fun to be around

and my father was glad

to be home from the war,

working the only job

he would ever have.

While reading the above lines it also occurred to me that high tide temporarily protects a whole swathe of shore and water creatures that live on the edge. When the tide ebbs weaknesses and vulnerabilities appear for all to see. Predators, of course, know this. Meek also knows this and ponders the fragility of family life.

Expectations play a significant part in the way we read literature. Perhaps poetry especially. A remembered tone may pull us in. Perhaps a hardscrabble story of working stiffs grabs us. Next the details may enchant our sensitivities with their unexpected simplicity. Finally, we look for the denouement and uplifting catchall. Meek slyly removes this last element in his poem How to Make Meatballs and substitutes a more diabolical and witty ending that smacks of life’s true realities. The poet concludes his poem,

The meatballs baked while I fried

eggs, bacon, and home fries

for the working girls and drunks

who stumbled in.

This was before Tony went away

for printing twenties in his basement,

before Joey broke in and stole our TV,

and the bank took their house.

Sometimes goodness can only be defined against a background of its opposite inclination. In his poem Miss Maloney, Meek’s persona teases out a moralistic outrage from his readers using memories of welled up juvenile cruelty. Meek’s classmates perpetrate this meanness against their inexperienced but well-meaning fifth grade teacher. The poet joins the classroom festivities with gusto. His over the top description signals his own disgust at his collaboration. The piece opens by setting the stage,

A doll, my mother proclaimed,

after meeting Miss Maloney

the new fifth grade teacher.

Just out of Bridgewater State Teacher’s College,

an eraser over five feet tall,

natural blond hair in a bun,

blue eyes in a field of freckles.

Smiling, she invited us

to set goals for the year.

At recess, our war council convened.

We aimed to make her cry

for being so pretty and perky.

Throughout these well-structured poems, Meek champions an almost Aristotelian sense of goodness and moral rectitude. His unabashed didactic bent seems unforced and infused with humility and a happiness born of intellectual truths. The word “organic” comes to mind. Refreshing. Very refreshing.

Reader Comments