*

*

Review by Off the Shelf Correspondent Dennis Daly

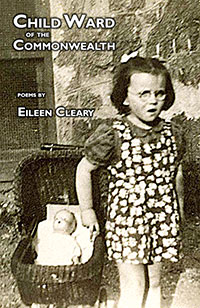

Poignant to the point of defining poignancy, Eileen Cleary’s first book of poems, Child Ward of the Commonwealth, shakes the soul with her truth-telling narratives of childhood trauma and dysfunction. Cleary somehow melds a mature poetic sensibility with a child’s wide-eyed ability to see the world’s wreckage with wonder and awe. Her persona relates adventures of fairy-tale-like brutality, not unlike fables from the Brothers Grimm. However, Cleary’s anecdotes are not mythologized; they are direct and very personal.

Child Ward of the Commonwealth

By Eileen Cleary

Main Street Rag Publishing

www.MainStreetRag.com

Charlotte, NCISBN: 978-1-59948-746-556 Pages$14.00

One of the collection’s most compelling poems, entitled On What to Forget, stakes out the mnemonic territory utilized by Cleary and delivers illuminating slivers of juvenile reasoning and adult pathos to boot. The piece begins with a four-year old cowering under a table as the skin of her sister’s arm, aflame from a kitchen fire, literally melts. Through negative constructions the narrator tries, through time, to assuage the little girl’s guilt and place it where it belongs. The poet says,

Not your mother.

She wasn’t cooking,

didn’t leave that pan to boil,

didn’t leave her children

under the porch,

hide-and-go seeking

through its lattice.

Ready or not here I come!

into the kitchen,

She wasn’t even there.

Grow older, grow smaller

because you did nothing, you

did nothing but hide

Left to their own devices, human youngsters turn feral like other mammalian offspring in synonymous circumstances. In her poem When the Social Worker Took Me, Cleary’s persona explains with perfect juxtapositions and impressive, if hair-raising, choice of specifics. Consider these lines,

…I watch

over myself—teach myself

to speak. I say lipshick or pisgetti,

poke holes in my tights, pull snarls

from my hair, toss and catch

a puppy on the stairs—I hide

in an attic, clamor through the halls,

map my slap-dash kingdom

in crayon on the walls. The neighbors

dial phones, shut behind their doors.

Childcare in the best of circumstances can on a bad day lead to neglect or dubious disciplinary behaviors. Without the presence of permanent kinship, the possibilities of cruelty multiply exponentially. In her piece Toaster, the poet describes in straightforward language one such unseemly incident, an assault on her little brother,

The baby sitter shouts.

John, when will you get serious?

She jams Johnny’s hand

into the toaster while I freeze,

bury my own unbuttered fingers

into the pockets of my jumper.

He screeches like a barn owl,

hissing, and flapping his arms

against the brute walls

of the too-small room.

Children on the outside of family life hunger for inclusion. They dream dreams of especial treatment, stability, and comforting acceptance. A full belly and an unchangeable name are part of the deal. Denial of these perks breed resentment and pugnaciousness. Cleary’s poem Foster Care Definition ends via a fantasy culminating in a very real demand,

I learn the zebra knows its herd

because patterns dazzle

their family names across the green.

I want my name to dazzle too.

I begin to wish myself an elephant.

At St. Boniface’s, St. Mary’s, St. Joseph’s,

St. Francis’, back to my third grade

report on pachyderms, how I pray:

make me an elephant, God.

Let my skin wrinkle over my hide,

Not for the size, Not for the skin.

I want to be family. Let me in.

Throughout the bulk of these poems the narrator’s mother takes center stage, even when she is not there. Sometimes it’s not pretty. Family bonds, even in dire circumstances, resist tampering. Children love unconditionally. The poet’s piece How the Goldfish deals with strategies of remembrance and forgetting. Here is the heart of the poem,

My foster mother tells me forget,

but not to forget my birth mom

passed out across the front threshold,

how we kids only use the back.

So I forget:

How-dee-dow-dee-diddle o

Through our days and how she

Hums herself into a blanket.

How after again the ambulance

takes her, we play Wizard of Oz,

follow bricks through Flaxen

Park to a blackbird tower.

How when she’s back home

we think we wished her there.

How even on bad days,

her scoring paragoric—

Acceptance and reconciliation with old ghosts can be part of a healing process after years of hard knocks and open wounds. Cleary’s poem I’m Thinking of Re-entering My Body delineates such a curative progression. A damaged soul needs to be well grounded in flesh and blood. The poet’s persona seeks out her earthly shell in these lines,

We’ll have this reunion before it

thinks I’ve died and follows.

While it’s open to my custody,

keeping its musts of eat and drink.

When I re-enter, I like to think

we’ll scribble its history,

its journey erasable

without the ink of me.

Confessional poetry such as Cleary’s that dwells on brittle emotion and memory is difficult enough to write. But, when told through the eyes of a child or a maturing adult, that same poetry becomes both magical and medicinal. An amazing debut of an astonishing poet.

Reader Comments