Eagle Feathers #151–The Year Was 1872

By Bob (Monty) Doherty

The date was January 1, 1872, a time when Somerville would celebrate her incorporation from a thirty-year old sleepy town into a young city. One of her immediate priorities was public safety. Less than three months earlier, a fire destroyed the city of Chicago on October 8 and 9, 1871. It remained the worst fire in American history until the attack on the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001. The Chicago fire killed over 250 people, burned over 200 acres and destroyed over 17,000 structures.

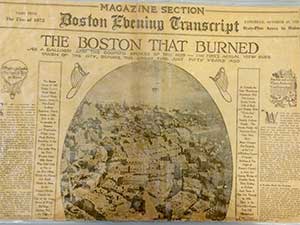

The following summer, insurance balloons were flown above Boston for the first time ever. Their purpose was to assess the city’s fire danger; and as a result, many insurance policies were cancelled. Chicago was such a fire prevention wake-up call across America and the world, that you would think it would never happen again … but it did.

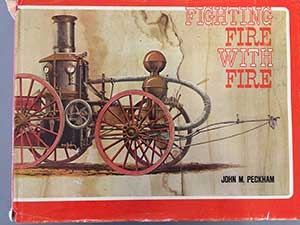

Just thirteen months later to the day, on November 9 and 10, Boston experienced its own conflagration. It destroyed over 776 buildings and consumed over 65 acres of downtown property worth over 75 million dollars before it was extinguished. Eleven firefighters lost their lives and 17 were severely wounded. The main reason for the fast spread of fire was a horse-flu called the Epizootic Plague that crippled almost all metropolitan fire horses including Somerville’s. As an emergency measure, five hundred men were added to Boston’s department to physically haul its fire apparatus. Outside towns performed half marathons under load, dragging their engines from over twelve miles away.

On notification of the fire, Somerville’s James Hopkins, in his first year as Chief, ordered his entire department to respond to Boston’s aid. They worked the fire at Winthrop Square until ordered to reposition to protect the historic Old South Meeting House/Church that was amazingly saved. One of the steamers, the Kearsarge-Engine #3, arrived by train from Portsmouth, New Hampshire just in time to help save the Meeting House’s steeple.

The last building to burn in this horrific fire was a foundry owned by Edward Revere Curtis, grandson of Paul Revere. He served in the Common Council of Somerville and was also a member of its Board of Alderman. Curtis Street was named after him.

Four years later in 1876, Somerville’s Mary Tyler, object of the poem Mary Had a Little Lamb would help rescue the Old South Meeting House/Church once again. This time it was to save it from developers. She gave talks to hundreds of children and sold bits of yarn made from her lamb’s wool that were auctioned off for the cause.

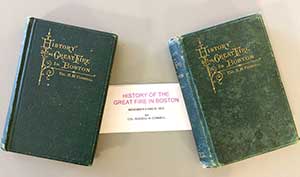

Colonel Russell Conwell, Editor of the Somerville Journal, felt that words had to be written to describe the horrific fire in depth. The following year in 1873, his book, History of the Great Fire in Boston, went to press. Its dedication read, “To the City of Chicago who, notwithstanding her recent suffering and losses, was the first to offer assistance in the hour of Boston’s greatest trial.” In this way, Chicago became America’s second City of Brotherly Love.

Reader Comments