*

From Michael Casey’s website:

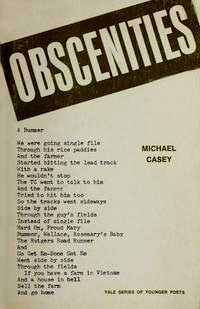

In 1972, Michael Casey won the Yale Younger Poets Prize for Obscenities, a collection of poems drawn from his military experience during the Vietnam War. In his foreword to the book, judge Stanley Kunitz called the work “a kind of anti-poetry that befits a kind of war empty of any kind of glory” and “the first significant book of poems written by an American to spring from the war in Vietnam.” Its raw depictions of war’s mundanity and obscenity resonated with a broad audience, and Obscenities went into a mass market paperback edition, and was stocked in drugstores as well as bookstores.

In the decades since, Casey’s poetry has continued to document the places of his work and life. Then and now, his poems foreground the voices around him over that of a single author; they are the words of young American conscripts and their Vietnamese counterparts, coworkers and bosses, neighbors and strangers. His compressed sketches and unadorned monologues have appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, and Rolling Stone. There It Is: New and Selected Poems presents, for the first time, a full tour through Casey’s work, from his 1972 debut to 2011’s Check Points, together with new and uncollected work from the late 60s on. Here are all the locations of Casey’s life and work – Lowell to Landing Zone, dye house to desk – and an ensemble cast with a lot to say.”

I talked with Casey on my Poet to Poet/Writer to Writer TV show at the Somerville Media Center studios.

Doug Holder: You started out as a physics major at Lowell Tech, but you wound up as a poet. How did this happen?

Michael Casey: As it turned out I was not a good match for physics. I was always a big reader and I enjoyed the English classes I took. I only took physics because my friends were. The teacher who inspired me was William Aiken. He was a very nice man and he encouraged my writing. He gave me lists of magazines where I could send my work. He influenced my style. When you grow up in New England like I have – you try to write like Robert Frost. Aiken did not care for my Robert Frost-like poems but he did like my poems about mill workers. When I grew up I worked in textile mills and even one that produced fish sticks.

DH: You were a military policeman during the Vietnam conflict. Your Yale Younger Poet Prize-Winning collection titled Obscenities was based on your experiences. Tell me about your time in the military police.

MC: At the beginning of your army experience you are given a battery of tests. They test you about leadership potential, your inclination toward adventure. They asked me if I would like to be a mountain climber or a librarian. I said librarian. My intelligence test indicated I would be best placed as a military police officer. This was a very good job in the army. People would enlist just to get the job. But it seemed every Irish name over 180 pounds went to the military police school. I was uniquely unsuited to be a policeman. People would enlist just to get that job. You would see a lot of humanity pass by on any given day. Ask any policeman what does he or she think about the goodness of mankind, you would be laughed at. They see the worst in mankind. It was fairly well-established that members of the military police were in the black market in Vietnam. We were privileged in many ways. I think because we were the last defense for the officers. They could call on us if they needed help.

DH: Were you writing poems then or was that after the fact?

MC: Yes. I kept my ears open and I listened to the stories. So not all the stories were mine by any stretch. The idiom of the soldier was fascinating. You know, I would write idiomatic poems about mill workers. So it was a logical step to write about army life. I remember Pogo – the comic strip – Walt Kelly used the language of the soldiers who were denizens of the South’s swamp lands. The way they talked was fascinating to me.

DH: Diction adds a lot to poetry.

MC: Yes, it does. Like the boxing manager, whose fighter loses. He might exclaim, “We was robbed!” Well, if he said, “We were robbed!” it wouldn’t have the same effect. But in some cases its use is excessive. In the case of the movie Raging Bull, there were too many four letter words used. It became too much for me. That being said, every time you walk down the street you hear something interesting, to my way of thinking.

DH: In your bio it said that you were the first poet to write about the soldier’s experience in Vietnam.

MC: That is a bit exaggerated. There were a lot of Vietnamese who wrote poetry about it. Bill Ehrhart came out with a chapbook of poetry before me. But I was one of the first.

DH: You have a deep connection to Lowell, like Paul Marion – the founder of the Loom Press – who published your new collection.

MC: Yes. I grew up in a house in Lowell where my parents never used any four letter words. But when I worked in the mills there was no restriction on language there. Also, there were always a lot of immigrants in Lowell, Portuguese, Cambodians, etc. In Lowell, I got used to different languages. And yes, Marion has been a big supporter of my work.

Reader Comments