*

Review by Dennis Daly

(Off the Shelf Correspondent)

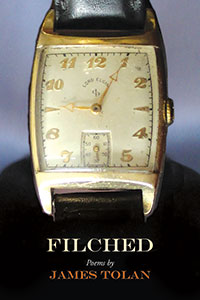

Without an intermediary, a thickly (or at least thinly) constructed persona to absorb sentiments backwash, confessional poetry often erodes and collapses of its own weight. Some of it can be downright dangerous. In his new book, Filched, James Tolan avoids that pathetic destructiveness using tonal restraint, irony, and damn good storytelling. Each poem Tolan breathes onto his pages burns with a purloined joy, freed from time’s untoward tyranny.

“Filched”

Poems by James Tolan

Loveland, Ohio

www.dosmadres.com

ISBN: 978-1-939929-79-2

69 Pages

In his poem The Big Sleep, Tolan summarizes his father’s last ambulance ride to the crematorium in some detail. Since the poet had opted to stay in Brooklyn at his teaching job during the funeral rites, he could not really know the particulars first hand. His absence generates the ambiguous emotional power that drives the poem. Like many who grieve by fixing their attention on a seemingly random oddity, the poet remembers the book that he had been teaching his class – Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep. He uses this book to order and give meaning to the dysfunctional apathetic world surrounding him. Here is the juxtaposition that conferred significance on Chandler’s book,

Some hospital joe wheeled him down the long, white hall,

While Santa Anas spilled desert across the town.

While I ducked the rain in Brooklyn, my collar against the storm,

sodden strangers plunging with me to the train,

an ambulance drove him slowly to where the fires blaze,

hot enough to roast flesh and bone to scrap and ash.

While undertakers readied to fit him for the flames,

I taught the book that I had plucked

From the rack beside his Lazy Boy.

He told me to take it, if I wanted.

He was done, tired of Chandler anyway.

On a fall day in Vegas, strong winds whipping in,

Tourists went on laying down their bets

According to Tolan, the River Styx has nothing on Waukegan Harbor in Lake Michigan. The harbor apparently has a great view of Zion nuclear plant (now decommissioned). His cautionary piece, Tag, promises to a bunch of boys playing on the beach a paradise to come on the opposite shore in the form of “loose-limbed girls.” But, like all paradises promised, falls terribly short. One of their number claimed to have travelled there and, disbelieved, is pelted with dead fish during a game of tag. Deadly irony and un-childlike horror conclude the poem,

Allied against his all too certain lies’

we bore what arms were given us

and fired

the rank corpses that fit so nicely

into the empty pockets of our hands.

Bombarded, he wailed and snarled,

Fish-stung from the beach.

Our ammunition caked with sores,

we wiped our hands off on the sand,

the sand off on our jeans,

and went on, half hearts denying

all of us were It.

Filched, the title poem of Tolan’s collection, works wonderfully, both tugging the reader’s heart-strings and engaging his or her intellect with show-stopping irony. The poet chose a perfect metaphor, his father’s old watch. Moments of pathos seem to implode into great complexity. The poet craves love’s time, but settles for a memento, a timekeeper. He fabricates his life as it should be, using his father’s swiped watch as both anchor and proof. Tolan describes his childhood crime this way,

I found it among tie pins and cufflinks in his top drawer,

filched it years before I knew the word,

knew only that I wanted something I could take from him

who knew work and the bar better than home,

something I would have never called

beautiful and ruined.

Crystal scratched, leather dry and stitching frayed.

He never noticed it was gone

Boyhood, as I remember it, sparked with adventure and marvel. Imagination could transform the intimate into the epic. But there was a dangerous downside. Not all of us made it through those years. These were the days before well-meaning helicopter parents stifled the rough and tumble coming of age rituals of young males. Perhaps saving some, but weakening the genetic trajectory of many more. With this in mind, Tolan’s brave poem, A Wild Rumpus, after one of the boys pours gasoline on the play-battlements, ends in an affecting parental prayer,

… he doused

the ungarded enemy fortifications

with the contents of that quart

then torched it with a Bic. My team

commenced to hooting and high stepping.

Even the losers joined in, two armies

circling the flames. This the happiest

I’d ever seen sober people be: boys disarmed

around a fire lapping blankets and dry wood.

Angels of infernos and safe distance,

be as kind to my boy. Lead him to joy

and sanctuary from joy burst into flame.

In another meditation on boyhood entitled Junuh at Nine, Tolan considers his evolving relationship with his son, Junuh. He balances his responsibilities with Junuh’s need for independence and a sense of self. The poem has a good feel about it. Despite the poet’s obvious closeness to his subject, he manages a tonal objectivity that intellectually affirms life and fate. I like this piece a lot. Tolan opens his argument thoughtfully,

My son has begun to set out on his own,

to form allegiances with friends

whose secrets he, by age-old code,

is compelled to keep.

His world more and more his alone.

Already, Jordan has broken a boy’s arm.

Daquan was caught at recess with a blade.

Jesse pummeled Andre. And Junnuh

has no idea how

his fake leather coat was torn.

Uplifting and victorious, Tolan’s poems transport the reader through the real world of sensitivity and timelessness. Mortality holds no sway here. With each reading this gritty collection offers solace as it draws one further into its whirlwind confrontation of everyday humanity. Tolan, who unfortunately died this year, lives within his books and deserves our profound prayerful gratitude.

Reader Comments