*

By A.D. Winans

I read in an article that Charles Bukowski’s books of poetry are a stealing magnet at many bookstores – including our own Porter Square Books – thus the article…

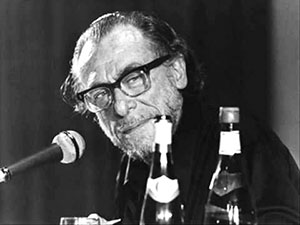

This is an interview with poet A. D. Winans concerning the new memoir he penned dealing with his relationship with the “dirty old man” poet himself, Charles Bukowski. In Winans’ new memoir, The Holy Grail: Charles Bukowski and the Second Coming Revolution, the author tells the fascinating story of a personal and literary friendship with none other than the bohemian bard, Charles Bukowski. Winans takes us back to the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s and gives the “out of school” report about this prolific, hard drinking, and womanizing writer who changed the face of the small press. Bukowski, best known for writing the screenplay Bar Fly, featuring Mickey Rourke, was also a staple of the famed Black Sparrow Press. Winans defines his friendship with the poet through their poetry, letters, and “bad elbows.” The book also explores Winans’ acclaimed literary magazine, Second Coming, and the fecund literary milieu it occupied in San Francisco and the world small press movement during the 70’s, and 80’s. I conducted an interview with Winans via the internet, from his home in San Francisco.

DH: What do you feel is Bukowski’s single most important contribution to literature and or poetry?

ADW: I think Bukowski himself answered that in an article he wrote for Second Coming. He said, “My contribution was to loosen and simplify poetry, to make it more humane. I made it easy for them to follow. I taught them that you can write a poem the same way you can write a letter, and that there need not be anything necessarily holy about it.”

Hemingway did much the same thing with prose, and then along came Bukowski to do the same thing with poetry. And I’d add that Bukowski’s letters were often poetic gems. The art of letter writing has all but disappeared, lost in email transmissions that too often are cold and impersonal.

DH: Your own entry into poetry was fueled by the injustice witnessed while you were in the service in Panama. Would it be fair to say that politics and social injustice were your first muse rather than a poet or a specific body of work?

ADW: My first influence came from musicians and not poets. When I was in high school, I would sit in my room for hours listening to Hank Williams senior sing his haunting songs. When I came home from Panama, my mother said, “You are not the same person. What did they do to you?” What they did was to take away my innocence. The things I saw there burned themself into my social conscience. It took me over thirty years to put my experiences down on paper. It’s all there in This Land Is Not My Land. Green Bean Press published some of the poems in a small chapbook, and Harold Norse encouraged me to expand the book, which I have done. I just haven’t gotten around to sending it out to a publisher yet.

DH: What similarities do you see between yourself and Charles Bukowski, both as a man and a writer?

ADW: We both went to city college, we were both heavy drinkers, we were both womanizers, we both (to a large degree) wrote for the same audience, we were both in trouble with the law, we both came up through the small press, we both saw the futility of writing workshops, and we both realized a writer could either spend his time writing in relative isolation, or he could hang around with other poets in cafes. We both chose the former over the latter.

DH: Can you describe the milieu of North Beach in the 50’s and 60’s, that was your spawning ground as a poet. Was this area of San Francisco as significant as Greenwich Village in NYC?

ADW: North Beach was the West Coast equivalent of Greenwich Village, and many of the poets (Ginsberg, Corso, Micheline, Kaufman) frequently spent time shuttling from one place to the other. The Cedar Tavern was a focal point for NY poets. In San Francisco it was The Place (presided over by Jack Spicer) and The Co-Existence Bagel Shop, where Bob Kaufman made his home. Gino and Carlo’s was another favorite hangout, and you would often find Spicer and Richard Brautigan there. I didn’t visit NY and the Village until the 60’s, and it of course had completely changed by then.

DH: If it wasn’t for little magazines and small presses, do you think guys like you and the BUK would have a platform or a venue for your work?

ADW: No, I don’t think we would have. Other than Hank having an early story of his published in STORY magazine, the great body of his work appeared in the “Littles” He was published in Penguin Poetry Anthology, but those were isolated incidents. Early on, I had poems accepted by Poetry Australia and even sold some short stories to the Berkeley Barb and Easyrider (a biker mag), but it wasn’t till much later that APR (American Poetry Review), City Lights Journal, and a few academic journals began to publish my work. Later, Gale Research paid me a thousand dollars for a 10,000 word autobiography and Brown University bought my archives. In the last few years I have been included in some important anthologies, like Thunder Mouth’s Press’ The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry. I don’t think much of this would have been possible had I not been first published in the small presses.

DH: You started an acclaimed literary magazine in the early 70’s, Second Coming. What was the mission statement of this magazine? You had a special Bukowski issue, how was that received?

ADW: I don’t know if you could say that there was a statement; it was much more of a personal mission. I felt at the time that a lot of crap was being published and I wanted to start a magazine that would return to the spirit of the 50’s and 60’s. The Bukowski issue was a success in that Bukowski himself said it was the best unbiased issue ever done on him. The special Bukowski issue, my own North Beach Poems, and the California Bicentennial Poets Anthology were the only Second Coming issues and books that turned a profit. It’s sad but true that too few poets support the magazines that publish them.

DH: So many artists and writers are afflicted or choose to afflict themselves with drugs and alcohol. Writers, especially young writers tend to romanticize this lifestyle. You and Bukowski had serious problems with these demons. Does this lifestyle help the writer in terms of his creativity? Why do so many turn to it. Is there something about the sensibility of an artist that makes it attractive or even necessary?

ADW: That’s a lot of questions rolled into one. Poets and writers do seem to be drawn to heavy drinking, and a good number of them are drawn to drugs. Alcohol was my drug of choice. I started drinking in my junior year in high school and became a heavy drinker in Panama. There was nothing romantic about it. I was more or less a social alcoholic. Put me in a bar and I’d drink myself into a stupor. Unlike Bukowski, I never drank and wrote at the same time. I tried a few times, but what came from it were poorly written poems. I can’t speak for other writers as to whether it would help their creativity or not. It obviously helped Buk, but I don’t think it helped me in the least, and I never drank the day after a night of heavy drinking. I hated those hangovers. It was when the hangovers began to last two days that I knew I had to stop heavy drinking. I limit myself to two drinks these days and seldom go to bars.

DH: You write in the book that Bukowski was far from a saint. He could be brutal with his friends, unfaithful to his women, treacherous in his business dealings, etc. Yet you loved him. Why?

ADW: I admired his persistence and grit. His drive to make it to the big time. He developed a persona to achieve that goal. I also admired his giving up the security of the post office to write full time, and at an age it would not have been easy for him to find another job. I admire his honesty with the written word, although his honesty did not always show itself. None of us are saints, there are things in my past I am far from proud of, but I can honestly say I never set out to deliberately hurt anyone. In my book (The Holy Grail), I tried to treat everyone fairly. With Buk, he had this thing about not wanting to get too close to people and when that would happen, he cast them aside, or ridiculed them in poems and short stories, and even bragged about it. But in all fairness, he stopped doing this, after he became a success. So I guess I loved the best in him and tried to overlook his weaknesses.

I might add that the Buk said to me, “To live with the Gods, you first have to forgive the drunks.” Early Bukowski, when he was drunk, was not a nice person. When he was sober, he could be shy, and quite likeable. In the end, however, his art prevailed over his persona.

DH: Bukowski is sometimes mistaken for a “Beat” writer. How would you classify him?

ADW: I hate putting anyone in a category. Bukowski told me he was never a Beat. Let me quote you from a letter he wrote me, “I never liked the Beats. They were too self-promotional, and the drugs gave them all wooden dicks or turned them into cu**s. I’m from the old school. I believe in working and living in isolation. Crowds weaken your intent and originality.”

Well, Bukowski remained true to the latter part of this statement, but one could certainly question his comment about the Beats being too self-promotional. I mean Ginsberg certainly was a master at self-promotion and Ferlinghetti isn’t far behind, but Bukowski promoted himself pretty well too. If I were pressed I would say Bukowski was a Bohemian, as was Jack Micheline, although Jack used the Beat handle to his advantage when it was beneficial to him.

DH: Do you see any new Bukowskis on the horizon?

ADW: No, I don’t.

DH: Do you think the small presses today are as effective as in your salad days, in terms of getting the “word” out?

ADW: The small presses have always had problems with distribution. They simply lack the money or power to gain the attention of the established media, and most small press publishers lack promotion skills, as well. There are of course exceptions, but they are few and far between. Second Coming was never a money maker, but I got the word out well enough. I left copies of the mag in doctor and dentist offices, where you had a captive audience. There were also bookfairs and library conferences where we participated, and COSMEP (Committee of Small Magazine editors and Publishers) helped promote and distribute books to some extent. The most important thing to come out of COSMEP was to provide a kinship among small press editors and publishers. Those were fun times. We were thumbing our noses (in the 1970’s) at the collective masses, and having fun doing it. That doesn’t exist today.

I know there will be people out there who say the internet and the web have provided a background where more people can see a poet’s work, but there is no evidence whatsoever that this has resulted in any significant sales. In fact, if you can read the work free, why would you want to pay to read the same poem in print format? Well some of us still feel strongly about the print world, but I don’t know about its future twenty, thirty years from now.

DH: Do you think Bukowski’s corpus of work will be used in courses at colleges around the country as part of the literary canon?

ADW: I don’t suspect that this will be the case. The academics have not seen fit to give him the proper recognition that his work deserves. But who knows? Bukowski may be required reading fifty years from now, or he could be forgotten. Either way, Bukowski would be laughing his ass off.

Reader Comments