Steven Ablon is a psychiatrist whose main purpose as a poet is( in his words) “to break your heart.” Ablon, a Harvard Medical School faculty member who is well-seasoned in the practice of psychoanalysis, is acquainted with heart break. In his poetry he wants his words to be strongly evocative. He wants to reach the reader on a visceral level.

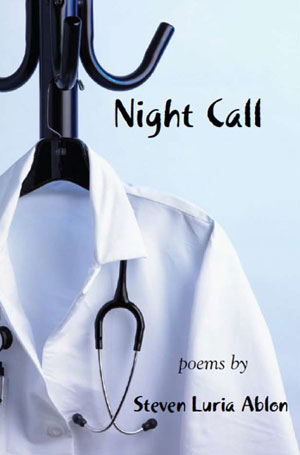

And indeed Ablon achieves this with his new book of poetry “Night Call.” Neeta Jain, Poetry Editor of The Journal of General Internal Medicine writes:

“In Night Call, Ablon slows us down so we can examine moments in medicine with him. He balances harsh, clinical reality of human frailty with the sweetness of compassion. A master poet, Albon uses poems to expose this tension as he masters medicine from student to physician.”

I talked with Dr. Ablon on my Somerville Community Access TV show “Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer.”

Doug Holder: You practice psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud of course is the father of psychoanalysis. Does this come into play in your poetry?

Steve Albon: I love poetry. Freud’s interest in the subconscious, the dissociative method—I think these are basic parts of poetry and analysis. Like free association—you work with whatever comes to your mind, and go from there. When you begin writing—writing a poem—you sometimes end up in a surprising place you didn’t expect to. I’m in a workshop where we use phrases as prompts and then just write for five minutes —whatever comes to mind. We see where it leads us. Sometimes you can get material that builds into a poem.

DH: I have run poetry groups at McLean Hospital for years. I find poetry can be very therapeutic. Your take?

SL: I don’t use poetry myself. I think it is tremendously therapeutic though. It is for me my writing source of comfort and awareness.

DH: Well life is essentially chaotic. Doesn’t writing bring some coherence—provides a narrative to it all-so to speak?

SL: It gets you in touch with things, and brings coherence to things you weren’t fully aware of. Like in my poetry collection “Night Call.” I went to medical school and went through all kinds of painful and difficult things as a young man. At the time I didn’t have time to think about it. Now many years later all of this comes up. Probably because I have enough distance to deal with them.

DH: You quote Goethe in your introduction. “We are, ourselves, at last, dependent.” Doesn’t this fly in the face of the American Western mythos of the stranger coming into town—the lone gunslinger—taking matters in his own hands?

SL: (Laugh) I think we would agree that there are some situations that you have to be strong and independent. But underneath it all we long for relationships, support, love, and connection. Connection is what sustains us. People try to push this aside and minimize it. If you do this you miss out on a lot of important things.

DH: In your poem Café de Paris, in your new collection, you are in a café with an attractive woman. A nefarious mole on her leg spoils the idyllic moment. As a doctor are you more on the lookout for pathology than the average Joe?

SL: Well as doctors we know more than the average person about pathology. We know a mole can become a melanoma. We know the consequences. We have seen patients struggle with things like these.

DH: William Carlos Williams, a doctor and poet, and author the groundbreaking book of poetry “Patterson” wrote about of all places a very pedestrian Patterson, N.J. He thought that poetry should reflect the “local,” “real life.” Your poetry is accessible, and certainly deals with life the way it is, without grand theatrical flourishes.

SL: I don’t think poetry should require looking up references. It should have an immediate impact in its own right. Much like Robert Frost. You read it, and it seems to be on the page very powerful. There is meaning behind it but it is not obscure. In that way it is poetry of everyday life.

DH: You deal with death in your poetry. Death is a fact of life. Do you think we try to push it aside—or don’t deal with it in Western society?

SL: So much of poetry deals with death. It is part of life—not just medicine. I think Asian cultures are more accepting of it. It is a hard fact of life. As P.T. Barnum said “I’m not going to get out of this life, alive.’

DH: You studied with Barbara Helfgott Hyett. What constitutes a good teacher of poetry?

SL: Barbara is very good teacher. She can work with each person’s style. You are not expected to fit in her way of writing. You find your own voice. She is incredibly generous and loves to see the people she works with succeed. She always tells us to write a poem that will “break her heart.”

*

Cadaver

The lesson for today is life

inscribed in bones we dig among,

muscled, tendoned, the ruined veins,

heart as frozen as gray snow.

The face is the burnt white moon

raveled, the seas scalpelled for us

a thousand times without reproach.

I turn the grooved brain in my hand.

Which lobe for laughter, which regret

stinking of formaldehyde.

Who kissed the crater cheek, this chin,

the death we call Penelope.

*

from “Night Call”

Reader Comments