— Photo by Terence Clarey

By Terence Clarey

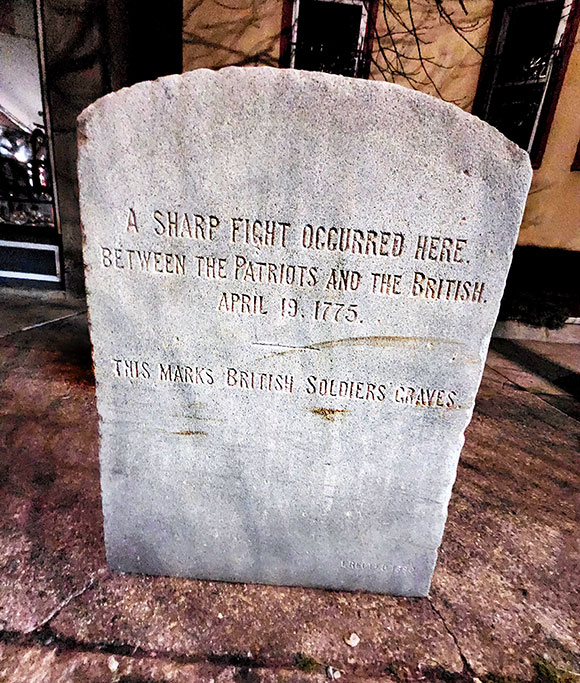

On a sidewalk, near the curb between a bicycle shop and a three-story apartment building, on Elm Street, Somerville, just east of its intersection with Beech and Willow Streets, stands a small granite marker, usually obscured by parked cars, with these words chiseled on its face:

This marker is one of the few remnants that tell of this small event; part of a far grander event which occurred 250 years ago this month. The date, April 19, 1775, was, of course, the day of the Battle of Lexington and Concord between British soldiers and local colonial militia, which began the war that would culminate in the birth of a nation. Although this “sharp fight” was a small piece of a much larger story, had things played out differently, it could have changed the course of the battle and later events.

The story is well known to almost every American adult with even the slightest familiarity with American history. General Thomas Gage, Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Commander of British military forces in the thirteen colonies, was hoping to repeat his success of the previous September, when he launched a pre-dawn raid to seize gunpowder collected by colonists at the Powder House in Somerville (then part of Charlestown). They were angry at the British government’s recently enacted policies that the colonists felt curtailed their political, economic, and personal liberty, including stationing soldiers in Boston.

In that raid, British soldiers were rowed up the Mystic River to Ten Hills, Somerville, where they marched overland to the Powder House, which stands today near Tufts University, seized the powder, and returned to Boston without any opposition. He had hoped to deprive the colonists the means by which they could launch any hostile action against British soldiers or loyalist citizens, and by doing so, keep the peace.

On April 19,1775, Gage planned to row a force of 800 soldiers, across the Charles River to Cambridge, landing them near Lechmere, and then have them march to Concord, where his intelligence told him weapons and supplies were being stored by the colonists.

Unfortunately for Gage, Boston Silversmith Paul Revere, and his network of spies found out about his plan and Revere slipped out of Boston and went on his famous ride, where he and others alarmed the countryside. Another problem for Gage was delays and mistakes that caused the British to get underway much later than hoped. So, when the red-coated British troops approached Lexington, on the road to Concord, the sun was already coming up.

The British were met by a handful of militia collected on the village green in Lexington, and after a tense few moments, the British fired on the militia, leaving eight colonists dead and ten wounded. Not expecting any serious opposition, the British marched confidently on to Concord, where they seized and burned supplies they deemed a threat to the military government. The conflagration appeared so great to the militia from Concord and other area communities, who were observing from the hills overlooking the town, that they thought the British were burning it. A large number approached the North Bridge to reach the center of town and attacked a small force of British troops guarding the bridge.

With the countryside now fully aroused after hearing the news of Lexington and now Concord, the British troops beat a hasty retreat to Boston. They soon came under attack by colonial militia from surrounding towns. After enduring near constant attack, the beleaguered British troops were met by a relief force in Lexington under the command of General Lord Sir Hugh Earl Percy, who had brought artillery with him.

After regrouping, the British continued their long retreat to Boston. In Arlington, then called Menotomy, they were met by even more colonial attacks from behind trees, stonewalls, and houses. As the British forces approached the intersection of what is now Rindge and Mass Ave. in Cambridge, the British routed several colonials, and it was here that Percy was faced with a crucial decision. When Percy’s reinforcements had left Boston earlier that day, they had marched out across what was then known as Boston Neck through Roxbury, Brookline, and Allston. They crossed the Charles River near Harvard Square over what was then called the “Great Bridge,” where the bridge that connects Allston and Cambridge stands today.

The question now was whether the British troops should return the way they came or turn left on Beech Street, a few hundred yards from the recent skirmish, and go right on Elm, and march to the Charlestown Peninsula to be ferried over the Charles to Boston? Percy had originally hoped to camp on Cambridge Common, but Percy received intelligence that a large force of militia was waiting for the British at the Great Bridge, and decided to take the shorter route through Charlestown.

So, after a brief stop at a tavern near the corner of Beech St and Mass Ave, Percy led his troops down Beech to where the small granite marker stands today. Before doing so, he had unlimbered some cannon, which he had done earlier at Lexington to keep colonials at bay while the British regrouped for their return to Boston.

But for the small granite marker, the history books and accounts of participants are scant on what exactly happened next, but there is evidence that it may have resulted as part of a hastily devised plan by General William Heath, who had been put in nominal command of American forces by colonial leaders earlier in the day. The plan was to try to force Percy toward the Great Bridge, where over 1000 American colonists were waiting. By doing so, he could have defeated Percy’s force and compelled them to surrender. As Allen French writes,

“It is satisfactory to believe that not only had Heath prepared his ambush at the Cambridge bridge, but that he tried to make sure Percy should be forced into the trap … Let Heath have the credit, and the minutemen who perceived the crisis the honor, that a body of them stood out in the open, prepared to fore the regulars to take the southern road.”

Apparently, it seems that some Cambridge militia was sent to get onto the Charlestown Road to force Percy to the Great Bridge because as the British approached the intersection, they were fired on by a handful of militia who showed themselves in the road to Charlestown. Other groups of colonists fired on the redcoats, and Percy quickly placed two cannon on a hill behind the Timothy Tufts house, where the bike shop stands today, and was able to clear a path for the British. The decision to use the cannon was successful in clearing the road ahead, but the British took several casualties who were left behind after they cleared the intersection. The column would eventually make it back to Boston.

Had the situation not been as chaotic and had Heath been able to coordinate better with other commanders, this “sharp fight” might have had a more consequential impact on history as opposed to being nothing more than one skirmish of many. It is interesting to hypothesize about how history might have unfolded differently had the American colonial militia been able to prevent the British from returning to Boston, as it was a sizeable portion of the entire British force occupying Boston. The siege of Boston may have had a different character, and the evacuation of Boston might have happened much sooner. Either way it may be that more comprehensive details of this small part of a great historic event 250 years ago, may never be revealed, and the small marker will be all that remains as witness to history.