*

*

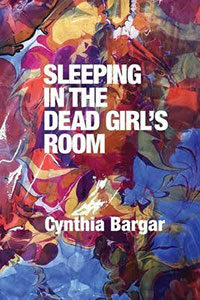

I had the chance to catch up Cynthia Bargar and communicate with her about her new collection of poetry, Sleeping in the Dead Girl’s Room. This is a challenging work about a challenging subject – mental illness. Having worked in the field of mental health for many years I have an acute interest in this book.

Doug Holder: Your new poetry collection, Sleeping in the Dead Girl’s Room, takes place at Glenside psychiatric facility where you were a patient. I worked for 37 years at McLean Hospital and for the most part patient care was good. But your poetry deals with some traumatic experiences that you had while in that institution. I guess the saying goes, “Great pain brings great art.” Does this speak to you?

Cynthia Bargar: Glenside Hospital was not a “therapeutic environment” for me. I was lucky that the two staff members I met on intake, Winston and Sterling, were good to me. They tried to show me the ropes and keep me out of trouble. They were a little older than me, sharp and funny, and I have always considered them my guides through that locked ward experience. Despite this connection, I wasn’t safe at Glenside. In my poem WATER CURE, I write of being raped by a staff person when I was granted a single room. When I was discharged, the chief (and perhaps only) psychiatrist told me, “You’ll be in and out of places like this for the rest of your life.”

I didn’t see this period as one of great pain. It was an adventure, capped by a visitation from my aunt, the one who presumably died by suicide when my mother was pregnant with me and for whom I am named. She spoke to me in an incomprehensible language, but there was a transmission. Only when I started writing the poems that became this book, did I remember her vaporish visit to Glenside. And then it took some years to see what that was about: haunting, entanglement.

If you’re saying that my book is “great art,” thank you. I don’t know if it’s great pain that propels artistic endeavors. For me, it’s obsession. I can never let go of that drug-fueled (Haldol) time at Glenside. And I was desperate to know what happened to my aunt and if being given her name and her bedroom and living in the house where she died for my first five years had seeded the haunting. I’m grateful to my poems for braiding this all together and then helping me to begin to untangle the braid.

DH: I know Sylvia Plath was referenced in the collection. Of course, Plath met her end by placing her head in an oven. A lot has been said about the romantic notions of the “crazy” poet. Did this influence you at all? Was Plath a sort of mentor?

CB: I first fell in love with Sylvia Plath as a depressed teenager reading The Bell Jar. I identified with the protagonist, Esther Greenwood, many of whose struggles seemed to mirror my own. Sylvia Plath lived in Winthrop, MA, for six of her childhood years. I was born in Winthrop and my early childhood was spent there. My aunt was three years older than her, and in my poem MY AUNT TALKS TO SYLVIA PLATH, I imagine them meeting in an afterlife. When I started writing poems I didn’t have any connection to the idea of the “crazy” poet and I don’t connect with nor have I been influenced by that notion. I came to Plath through her novel, way before I wrote or read poems. When I did discover her poetry, I was ecstatic.

DH: You have a Jewish background. How does the culture, your family influence you and your writing?

CB: In Jewish families it’s very common to name children after deceased relatives. I think there was an expectation that my parents would name me for my aunt. Oftentimes, the English version of the name, as opposed to the Hebrew, uses the first letter of the deceased’s name. So, I could have been a Carol or a Claire and that would have satisfied the tradition. But I was given my aunt’s first, middle, and last names: Cynthia May Bargar. My poem MIDRASH ON NAMING explores Jewish naming and the potential problems associated with naming a child after someone who died a violent death or by suicide, misfortune (dormant until stirred)/ will find the child.

I’m aware that keeping secrets within the family is not exclusively a Jewish phenomenon, but for some reason I do attribute the particular kind of unwillingness to speak about my aunt and the circumstances of her death to our being Jewish in what was as a hostile Christian environment/country. Assuming she died by suicide, I think the shame associated with that act and the fear of further stigmatization contributed to the silence.

Being Jewish — culture, family — has influenced all aspects of my life, including my writing. Some of my relatives spoke Yiddish and had limited fluency in English. The intonations of the Yiddish language probably had an influence on my writing.

DH: The book is dedicated “For all the women and girls whose stories were buried with them.” By writing this book, unearthing your story, did you have a catharsis of sorts – a sort of clearing out of the repressed demons?

CB: I wasn’t able to fully excavate my aunt’s story, which certainly was buried with her. But it no longer seems pressing to know exactly what was going on with her and exactly how she died. I’m okay with the not knowing. During the writing of the poems, I was immersed in the making and not the feelings. But once the book was published and I starting reading the poems to friends, family, and strangers, there was a shift in consciousness and I no longer felt haunted. I also developed compassion for my father, whose sister the other Cynthia was. We had a rocky relationship when he was alive, and because I was kept in the dark about the family tragedy, I didn’t have a way in, couldn’t understand what made him tick. I have come to see the poems as my way of making amends to him for judging him harshly.

DH: I was interested in your fractured sense of self that you had under the spell of manic depression. Was this some sort of coping mechanism?

CB: I think the “fractured sense of self” had to do with being haunted by the dead Cynthia, sometimes being confused by who was who, and often having to be differentiated (each of my grandparents referred to her as “my Cindy”). I absorbed much gloominess and grief in the house and family that may have fractured my sense of self. This fracturing was not just when I was in the throes of depression or mania, it was most of the time. It wasn’t a coping mechanism. On the contrary, it made it often impossible to cope.

DH: You often use the pronouns “You” and “I” in reference to your late aunt and yourself. You also used “the She” to refer to your aunt. Why did you do this? Is this a way to portray your confused mental state – the blurred lines between you both? Did you want to have the reader as confused as your younger self?

CB: Regarding the pronouns, I don’t know why I did what I did. I wrote the first poem in the book, CREATIVE NONFICTION, last, after Lily had accepted the manuscript. As I was writing it, “the She” presented itself and I liked it, so I went with it. The pronouns for me and my aunt are slippery because the line between us was sometimes blurry. The slip and blur are due to my being haunted and how mysterious that was.

I didn’t intend to confuse the reader and when I started distinguishing between the she who is not me, and the she who is me, in my mind it was a clarifying gesture. If readers are confused, that’s okay. I hope they enter my sphere and just go with it.

DH: Why should we read your book?

CB: I wouldn’t say anybody should read my book. I have heard from many readers who were moved by it. I think it resonates with readers because it illuminates some things about family secrets, memory and post-memory, and the human condition that many of us have experienced in very particular and mysterious ways. Even if their circumstances are different from mine, readers have told me they identify.

Reader Comments