Review by Dennis Daly

No writer distills history utilizing the form of poetic narratives better than Kevin Gallagher. In his latest effort, The Wild Goose Poems, Gallagher delves into Irish Americana, its background, and its sources. He uses a first-person sequence of poems on the rebel Irishman, then iconic Bostonian, John Boyle O’Reilly as the centerpiece of his collection. The poet leads into that sequence with a retelling of Celtic myth and finishes the book with a combination of classical myth and both local (Southie) and family lore. Think beginning, middle, and end. And that’s the way it reads.

Gallagher initiates his saga gently with a piece he entitles Birth of a Nation. Chock full of one damsel confined to a tower, one greed-filled king, the mysterious De Danaan tribe, one lovely princess, one white witch (or, in this case, a she-druid), one charming prince, and the bane of Celtic life, a stolen cow, this piece gives necessary foundation and entrances the reader in with its dreamlike sexuality. Consider these alluring and delicate lines,

As Cian stared at her

Eithlinn’s whole body went warm.

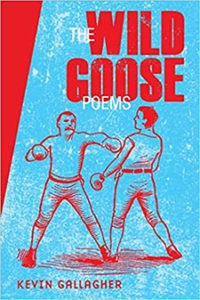

The Wild Goose Poems

By Kevin Gallagher

Loom Press

www.loompress.com

67 Pages – $20.00

She now saw what she only heard.

She now had what she only dreamed of.

They each declared their love

for each other in the same breath

then gently took off the other’s clothes

before they could breathe another.

He buried his face in her breasts

As she put him between her thighs

and sang a long slow psalm

of love up to the skies.

Cian wanted to live with her forever

Fenian to his core, John Boyle O’Reilly was sentenced for treasonous activities by a British tribunal to imprisonment in Australia. He escaped and as a poet, espouser of Irish causes, and editor of the Boston-based national newspaper The Pilot, earned regard and fame in America. In the poem 1867, Gallagher chronicles O’Reilly’s prison ship experience. The poet captures the below-deck claustrophobia this way,

There were three hundred of us without shadows

cast by lamps under the forward hold.

We welcomed each other with loud

Laughter curses of the most evil fear.

A warm stranger gripped my arm and whispered

come O’Reilly we are waiting for you.

He led me through a small door amidships

to the space where we waited to be slaves.

After O’Reilly’s escape and raucous welcome to Boston by two thousand cheering Irishmen, he faced the reality of his political circumstances. These opening lines from Gallagher’s poem Help Wanted explain,

Positively No Irish need apply?

We were half-starved and penniless

farmers without any tools for the city.

Most of us went working on the wharfs.

Women made factory shoes or sewed from home.

We had our will, our music, and our God,

but many wondered why we traveled here.

Like most Irish immigrants, O’Reilly melted into the stew of multi-ethnic America. He left his Irish grudges behind (mostly) and became more American than the Americans. Writing for The Pilot, he railed against the old insular hatreds carried as baggage into his new country. When Irish Orangemen marched in the streets of New York demeaning Catholics, they were attacked and four of them gunned down by Fenians. In Gallagher’s poem, Boston Pilot, O’Reilly laments the outrage,

Why must we carry our cursed island feuds

to disturb the peace of these citizens?

We are all aliens from a petty island

in the eyes of our fellow Americans. Here

the Orange have as much right to parade

as a Fenian regiment in green.

Both parties are to be blamed and condemned,

yes both Fenians and the Orangemen.

The fishing vessel, The Valhalla, moored in Gloucester and for a while in the Saugus River has become part of Boston Irish lore. Even Whitey Bulger, the notorious gangster, reportedly played a tangential part in this mythological drama. This reviewer, in a past life, met the Valhalla’s captain and off-loaded its cargo on the docks of Gloucester. It carried squid at the time. Later the same ship, tracked by satellite during the Reagan administration, was intercepted, carrying guns, off the coast of Ireland. Gallagher details the arms-running preparation in his poem entitled The Valhalla,

We had close to seven tons of mail-order

Weapons delivered by UPS.

We purchased them through ads in Shotgun News

by calling the 1-800 number.

We ordered ammunition cans, weapons,

training manuals, nylon rifle clips,

piles of M-16 magazines,

and rifle bags to hide them in the bogs.

We bought rocket warheads, anti-aircraft,

and 20,000 rounds home delivery special.

But the handguns, the rifles, and shotguns,

we stole those the old-fashioned way.

We packed all this in a couple of U-Hauls,

Then drove the trucks up to Gloucester Harbor.

My favorite poem in this collection, The Rose in the Elysian Fields, describes a classically based visit between the poet and his deceased father in the underworld. Mostly written in blank verse the piece, eleven pages long, conjures up an affecting blend of passion, wit, wisdom, and hope. Eight pages in, Gallagher inserts a lovely villanelle. Here’s the heart of it,

You can’t be dead for the rest of my life.

I’m so afraid that I will run out of time

but I don’t have any time to lose.

I cannot wait to see you until I die.

When you aren’t with me my life is a lie

and there is no such thing as the truth.

You can’t be dead for the rest of my life.

The rest of my life is too long a line

and I wouldn’t have anything to prove.

You can’t be dead for the rest of my life.

Poets who breathe in the rarefied air of Elysium, I’m told, change forever. Here’s hoping that Kevin Gallagher remains Kevin Gallagher.

Reader Comments