Come celebrate Robyn Hitchcock’s 64th birthday this Friday at ONCE Ballroom, where he will perform a sold-out show with his personal and professional partner Emma Swift.

By Blake Maddux

Immersing oneself in the discography of English singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock is the aural equivalent looking through kaleidoscope eyes into a series of fun house mirrors.

It is a musical world is one populated by – among others – Antwoman, Balloon Man, Toadboy, Wafflehead, and Madonna of the Wasps.

As defiantly non-mainstream as his oeuvre is, one can become acquainted with many of the nooks and crannies of popular music by following his recordings in all of the directions in which they proceed.

The 2002 release Robyn Sings consists entirely of Bob Dylan covers. His most recent album, 2014’s The Man Upstairs, includes covers of songs by The Psychedelic Furs, Roxy Music, Grant-Lee Phillips, The Doors, and a Norwegian band called I Was a King.

Hitchcock has also penned the songs I Saw Nick Drake, The Wreck of the Arthur Lee, and N.Y. Doll, each about a musician who was hugely influential and widely admired without ever being a pop star or a sell-out.

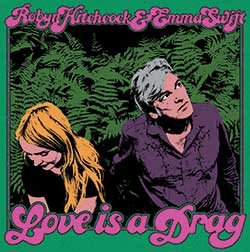

Robyn Hitchcock and partner Emma Swift’s “Love Is A Drag” single was released in October, 2016.

Having formed The Soft Boys in 1976, Hitchcock has gone on to record as the leader of The Egyptians – which included two members of The Soft Boys – and The Venus 3, which includes Peter Buck of R.E.M., Scott McCaughey of The Young Fresh Fellows and The Minus 5, and Bill Rieflin of Ministry and latter-day R.E.M.

Hitchcock will celebrate his 64th birthday this Friday at ONCE Ballroom, where he will perform a sold-out show with his personal and professional partner Emma Swift and hopefully previewing material from his forthcoming new album, which will be available on April 21.

He spoke to The Somerville Times by phone from a coffee shop in Nashville, where he has resided since 2015 (or, as he puts it, “I have a house here and my belongings live here, and sometimes I’m here with them.”).

The Somerville Times: How did Nashville become your new base of operations?

Robyn Hitchcock: I got together with Emma, my partner, who’s opening the show. She was living here when we met. And then we went all over the world, really, for a while. She was here already, but I’d been coming here. I made that record with Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings in 2003 called Spooked. I had some friends here, Emma had some friends here, more people seem to be coming in as we speak. My old friend Grant-Lee Phillips is based here. Brendan Benson also got in touch quite by coincidence. He didn’t know I was coming here. He wound up engineering and producing my most recent record [the forthcoming Robyn Hitchcock].

So there was Brendan, and there’s Grant, and there’s Emma, and then Gill and Dave. Gosh, they’re all on my – Dave isn’t, but Gill is – they’re all on my new record, along with some great local players.

TST: Do you get recognized in town?

RH: I do. Well, I get mistaken for Nick Lowe a lot, because I have glasses like his and white hair. They didn’t used to think I was Nick Lowe until I got these glasses. Now most people think I’m him. There’s a lot of musicians around here. On the whole, people don’t bother you. You do run into other musicians. There’s cafés full of them. I was just talking to some before you rang. It’s a wonderful place. It’s what it says on the label: Music City. Socially, it’s fantastic.

In a town like Nashville, I’m very pleased to feel like I’m part of the musical community. It makes me feel like I’ve learned a trade.

TST: Speaking of learning a trade, did you at any point in your life consider or pursue a non-artistic profession?

RH: No. I was reared to do one thing, which was to create art. If I hadn’t done this I would have been, I suppose, a comedian or some kind of academic stand-up guy or a writer or a visual artist. I would never have thought of going into acting. I would have been something to do with writing and maybe standing up and reading it all. I see myself as being somewhere between being a professor and a comedian if I hadn’t done this.

My listenership is almost entirely academics and artists. They’re all in that world. They either make music or they write or they teach. Some of them are in the legal profession, but they’re all that kind of a world.

TST: When did it become obvious to you that the 1980 Soft Boys album Underwater Moonlight had an audience that was not apparent at the time of its release?

RH: I didn’t really realize there was an audience until about four years after The Soft Boys finished, ’84-’85. People started telling me that we were selling records in America and people were listening to us on college radio and bands were citing us as an influence and stuff that we knew nothing of at the time. You know, we barely made it into the eighties. We were done by February ’81, so it was all sort of posthumous. And then I got together with some of the other guys from The Soft Boys as Robyn Hitchcock & The Egyptians, because I’d already started making solo records. So I kind of reincorporated some of the Soft Boys into there. Most of the time it was populated entirely by old Soft Boys when it was a three-piece, me and the bassist [Andy Metcalfe] and drummer [Morris Windsor]. So The Soft Boys had very kind of slow fade. At the time the whole thing didn’t seem to make any difference at all, really.

TST: Was there a specific inspiration for the names The Soft Boys, The Egyptians, and The Venus 3?

RH: Soft Boys was in part an amalgam of two William Burroughs books: The Wild Boys and The Soft Machine. And in part it was a concept of The Soft Boys as being a kind of invisible force that had a lot of power but was unseen. A kind of sexually ambivalent sort of, rather like Brits are depicted in Hollywood movies, you know, sort of stalking the corridors and calling the shots but unseen. In a funny way it was kind of how we turned out. We were very invisible people, but I suppose we had an influence, but not a big one.

The Egyptians came about because I liked Egyptian iconography. You know, Thoth and Anubis and Bast and Horus and Isis. All those gods with animal heads and silhouettes. I used the silhouette of Thoth, who was the god of wisdom or libraries or knowledge, for The Egyptians, and I used Anubis, who was the god of the underworld – the jackal god – for [the 1984 album] I Often Dream of Trains.

And The Venus 3 was, my father had written a book called Venus 13, a sort of comedy about people trying to have sex in space. I was calling them The Minus 3 at that point, because they were a version of The Minus 5, Scott [McCaughey] and Peter [Buck]’s band. And I looked at Minus 3 one day with my glasses off and it looked like Venus 13, so it mutated.

TST: How do you decide which songs by other artists are worthy of your treatment?

RH: I don’t decide. I sing any song that I would like to have written myself. If I don’t think that I would have liked to have written it then I don’t bother. Certainly the ones that I recorded on that last record of mine [The Man Upstairs]. The five on that are all songs I wished I’d written. Anything you find me singing at the end of the night, any encores, I’ll sing songs from my record collection.

TST: Do you, from a listener’s perspective, have a favorite decade of music?

RH: Well from my perspective, I suppose it goes from, you know, ’65 up to…a lot of what’s called “the sixties.” It probably goes from about The Byrds up to … I mean, David Bowie and Roxy Music were still doing great stuff into the eighties. But it’s what hits you when you’re that age, you know? If the first thing you heard was The Pixies, that’s going to mean more to you than going back to listen to The Velvet Underground or David Bowie. I was 14 when [Jimi Hendrix’s] Are You Experienced? came out. I was 15 when I heard The Velvet Underground. I was 13 when I discovered Bob Dylan. Those things are just hardwired into me. It’s the kind of thing that they can put on in a health club to make you feel young.

My psychedelic bar mitzvah was 1966. I turned 13, and that was the year of Eight Miles High [The Byrds] and Revolver [The Beatles] and Visions of Johanna and Blonde on Blonde [Bob Dylan]. I was just there. I coincided with it and that’s kind of why I make the music I make. If I’d grown up a decade later, listening to For Your Pleasure [Roxy Music] and Aladdin Sane [David Bowie] and Electric Warrior [T. Rex] or something, I’d probably be making a different kind. I love those records, but my approach would be different. Or another decade after that, and I was listening to Murmur [R.E.M.] and The Queen is Dead [The Smiths] and Doolittle [The Pixies]. They’re all good records; they’re all great records in a way.

Reader Comments